We are two hours removed from Pittsburgh as we roll into the small town of Oberlin, Ohio. It’s a gray day in early January. There’s a chill in the air, and few people are about. Students at the college make up half the population here, and most of them are away for winter break. As I look upon this quiet scene, I find myself thinking about the North Star.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, slaves fleeing the South for Canada used the North Star as their beacon and guide. The town of Oberlin served as an important stop along the Underground Railroad.

I am thinking, also, about Jason Molina, who graduated from Oberlin College in 1996. The songwriter was so captivated by the North Star that he used the image repeatedly in his lyrics. Molina died at an early age, but not before creating an extensive and admirable body of work. For my money, Molina’s song catalog may well be the most worthwhile thing to emerge from Oberlin College in the past 25 years.

I interrupt my reveries to ease into a parking space alongside Tappan Square. It’s a bit early to check into the Hotel at Oberlin — the college’s new, ultra-green, and LEED-certified hostelry — which is situated just down the block, facing the square. In a sense, everything in Oberlin faces Tappan Square. This is where town and gown converge, and where woke culture routinely confronts Western civilization.

The first stop on our itinerary is Gibson’s Bakery, the sixth-generation family-owned business that sued Oberlin College for defamation and other torts and was awarded damages (including attorney fees) in excess of $30 million. Throughout the litigation, the college maintained a stubbornly imperious posture, and now, with the interest clock running, it has hired additional attorneys to file an appeal of the judgment. The president of the college, Carmen Twilley Ambar, insists that the trial verdict is merely “one step” in what “may turn out to be a lengthy and complex legal process.”

Gibson’s Bakery, Oberlin, Ohio (Facebook)

Inside Gibson’s, the atmosphere is quiet and subdued. It’s clear that this little business and its owners have endured a great deal in the past three years, beginning with student protests in front of the store in November 2016. The protesters denounced the Gibson family as racist and claimed the store had a long history of racial profiling (none of which is true). Evidence introduced at trial established that the college facilitated these protests and that at least one senior college official actively participated in them. Following the protests, the college suspended its 100-year business relationship with Gibson’s Bakery.

The college claims that it merely sought to protect its students’ free speech rights. But Gibson’s did not sue the students. And no government actor attempted to restrain or stifle the students’ speech. Moreover, freedom of speech has never been recognized as an affirmative defense to defamation. All of this makes Oberlin’s litigation posture rather laughable — especially given the fact that Ambar is a Columbia-trained lawyer.

While inside the store, we chat with the Gibson’s staff and express our support for the principled and courageous stand that the Gibson family has taken in this matter. I remark that the institutional interests of the college and the personal interests of its senior officers seem to have diverged. Is it possible that these senior officers seek to prolong this litigation simply to preserve their jobs? Wouldn’t it be better for the college to put all this dreadful publicity behind it? What in the world are the school’s trustees thinking?

A more charitable explanation, perhaps, involves money — or the lack thereof. These days, Oberlin College is pinched for cash. It has operated for several years at a deficit, and it has struggled, amidst a torrent of bad publicity, to meet its enrollment targets. Oberlin has shuttered several buildings to save on heating and maintenance costs. It has also announced plans to eliminate approximately two dozen faculty positions over the next few years.

The Hotel at Oberlin (LinkedIn)

In any event, it’s time to take our leave of Gibson’s and check into the Hotel at Oberlin, a perfectly functional four-story box-like structure peering out over Tappan Square. Among all the buildings owned by Oberlin College, this is probably the one with the greatest marketability. But I foresee problems. Even if the college were willing to transfer title to the Gibson family, the building can’t be worth more than $8 to 10 million. And who’s to say whether the Gibson family would want to operate a hotel? Alternatively, suppose Gibson’s accepted title in partial satisfaction of their judgment, and then attempted to sell the hotel. Would there be any logical purchaser other than the college? Likely not. Oberlin College uses the hotel as a recruitment tool. Prospective students and their parents stay there when visiting the campus. In fact, the school’s office of admissions is adjacent to the hotel and can be entered through the lobby.

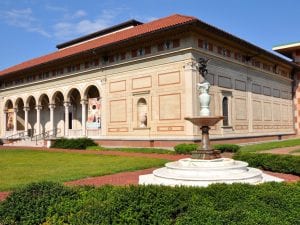

After checking in, we walk down the block to the second stop on our Oberlin itinerary: the Allen Memorial Art Museum, which is owned by the college (and also faces Tappan Square). I’ve read that the Allen houses one of the finest college art collections in the country, and my wife and I are anxious to see it — while it remains intact.

The fountain and façade of the Allen Memorial Art Museum (Yvonne Gay Fowler)

Much of the reporting on the Gibson lawsuit makes reference to Oberlin’s impressive $800 million endowment. Surely a small school with such a large endowment should be able to pay a $30 to 40 million damages award. But it’s likely that most or all of Oberlin’s endowment assets are held in trust and are therefore unavailable for the purpose of paying a judgement. And, by virtue of being held in trust, the endowment’s assets may be protected and beyond the reach of a judgment creditor.

Hence our visit to the art museum. This is where quite valuable and readily marketable assets are to be found. While perusing the collection, we quickly identify candidates for sale at auction. There are many, including portraits by the likes of Anthony van Dyke, William Hogarth, and Sir Thomas Lawrence. There is a small landscape by Cezanne that would likely fetch a very handsome sum (either at auction or sheriff’s sale). A Modigliani nude, set against a bright red backdrop, also stands out.

But if the college wishes to part with just one or two pieces whose auction value will easily satisfy the Gibson judgment, then my recommendation would be as follows: Offer the J. M. W. Turner painting “View of Venice” (1841), which is a lovely and luminous work. If the proceeds from an auction of the Turner aren’t sufficient to cover the amount of the judgment, then the college might also offer the Claude Monet painting entitled “Garden of the Princess, Louvre” (1867). This is a truly striking and stylistically transitional work, painted early in Monet’s career.

Claude Monet, Garden of the Princess, Louvre, 1867, Oil on canvas, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio

One of the nice features of the art auction market is that the auctioneer’s commission is paid by the winning bidder. Thus, Oberlin’s selling costs will be de minimis.

Of course, one can reliably predict that certain members of the faculty or the alumni community will grouse about the college voluntarily selling off pieces of its art collection — but desperate times call for desperate measures. And it’s possible that some well-to-do alum, or a Daddy Warbucks sitting on the board of trustees, will step forward to bid at the auction, and, if successful, return the artwork to the museum, either as a tax-deductible gift or as an item or items on permanent loan.

Feeling well-pleased at having devised a solution to one of the more pressing of Oberlin’s problems, we decide it’s time for dinner. We head around the corner (and away from the square) to The Feve, a rather pleasant little bistro that has, for several decades, enjoyed the patronage of students and townsfolk alike. (I’ve read that Jason Molina worked there during his student days in the 1990s.)

The Feve, Oberlin, Ohio (Oberlin Project)

After dinner, we hop in the car and drive about a mile to the third stop on our Oberlin itinerary, the men’s basketball game at Philips Gymnasium. It’s an 8 p.m. tip-off, with the Oberlin College Yeomen hosting the Battling Bishops of Ohio Wesleyan University.

The gym is rather modest, and the crowd is rather sparse — typical of Division III hoops. What is far less common is to spot the college president in the stands. She’s seated across the floor from us, in the front row, near the exit. I remark on this to a couple of students seated behind us, and they tell us that Ambar is a frequent presence at games. This seems a bit surprising. Shouldn’t she have more important things on her schedule, such as attempting to salvage the school’s reputation? Or restoring learning to its rightful place, ahead of social justice warfare and identity politics?

Maybe not. And, in any case, President Ambar pays little attention to what’s transpiring on the court, focusing instead on what’s flashing across the screen of her smartphone. To be fair, the game is not unfolding in a way that would excite much interest among fans of the Oberlin squad. The Yeomen are performing in a less-than-yeoman-like manner. At the close of the first half, they trail the visitors by 11 points.

When play resumes, nothing improves for the Yeomen. And, as the clock winds down to the five-minute mark, the Bishops hold a commanding 16-point lead. Then, slowly and almost imperceptibly, Oberlin begins to claw its way back. The students sitting near us begin to take heart and shout encouragement. The Yeomen respond to the fans’ growing excitement, and, with a minute to go, manage somehow to pull within five points. Now the grandstand is pulsating. All around us, the students are engaged in a frenzied demonstration of school spirit — something I never would have expected to see on Oberlin’s notoriously woke campus.

The final seconds of the game unfold in a way that is at once thrilling and excruciating. The noise level suggests that there may be a few thousand fans inside the gym, as opposed to the 200 actually present. Then, just at the buzzer, Oberlin sinks a three-pointer to tie the game. Whew!

After this momentous reversal of fortune, the overtime period plays out as an afterthought. The Bishops have lost faith, and Oberlin pulls away to win by a margin of nine points.

As we gather up our jackets and prepare to leave the gym, it occurs to me that the contest we’ve just witnessed might serve as an object lesson. No matter how far a team (or an institution) has fallen, a miraculous comeback isn’t altogether out of the question — assuming that team (or institution) has the requisite dedication, perseverance, tenacity, and commitment to fair play. I am tempted to ask some of the students whether they perceive a similar meaning, but my wife cautions me not to say anything that might trigger them. Still, I’d love to walk across the court and ask Ambar whether she has, perhaps, drawn the same or a similar message from the game. But I cannot. She bailed out at halftime.

We walk outside to the car, and I glance up into a leaden sky. There will be no North Star visible tonight. Silently, I begin to rehearse some lines from one of Jason Molina’s songs:

I heard the North Star saying,

“Kid, you’re so lost,

Even I can’t bring you home.”

Presumably, Molina was not thinking of his alma mater when he composed these lines. But on this night, they seem disturbingly applicable.

Michael Cook lives in Pittsburgh and writes occasionally about the troubled state of American higher education.