The Cathedral of Christ the Light in Oakland, California, is astonishing. From the outside, it appears as though a spaceship decided to land on the banks of Lake Merritt, while the interior reminds the visitor of an upside-down boat. Maple-stained slats rise high in the air, punctuated by light; at the front of the church, suspended above the altar, is a massive image of Christ, two fingers raised in blessing. The depiction looks like a projection onto a screen, but eager staff members assure visitors that the pixelation is a trick of the light.

Gregorian chant, the ancient song of the Catholic Church, feels out of place here, surrounded by the cold trappings of modernity. I know because I had the opportunity to play the cathedral’s magnificent organ, and the simple notes of Anima Christi drifted erratically in the alien space.

This article is taken from The American Spectator’s latest print magazine. Subscribe to receive the entire magazine.

If you’ve been in a Catholic church in the last sixty years, none of this is surprising. Chant doesn’t fit in the boxy, unadorned modern churches with which many Americans are familiar. The acoustics are too dry. What does mesh well is a drum set, an electric piano, and On Eagle’s Wings.

This disjointedness between ancient practices and art and their modern counterparts has been at the center of a burgeoning identity crisis within the Catholic Church. Some Catholics — perhaps inspired by the oft-invoked “spirit of Vatican II” — are eager to celebrate a contemporary liturgy that fits into a modern context; others are uninterested in anything created after the Council of Trent; and most fall somewhere in between.

Of course, this debate is not at all new. Plenty of Catholics (and non-Catholics) never liked the liturgical reforms that flooded the churches after the Second Vatican Council. In a rather famous instance in 1971, fifty-six British writers, musicians, and artists affixed their signatures to a letter asking Pope Paul VI to allow some parishes in England and Wales to continue celebrating the Mass in Latin. Paul VI agreed and issued what became known as the Agatha Christie indult.

Subscribe to The American Spectator to receive our latest print magazine, which includes this article and others like it.

But the indult was the exception, not the rule. For most Catholics, the latter half of the twentieth century was an age of innovative liturgies with brand-new music. Guitars, drums, and pianos found their way into churches, and organs were quietly removed or never even installed.

When the Oakland diocese completed its cathedral in 2008, it was intended to be a space that catered to that new form of music. But even as the new cathedral opened its doors, things were changing.

Just months before, Pope Benedict XVI issued what was arguably one of the most pivotal documents of his pontificate: Summorum pontificum. In that document, Benedict XVI stated that the Church had never abrogated the Latin missal promulgated in 1962 and that any priest in any diocese could offer Mass according to that missal.

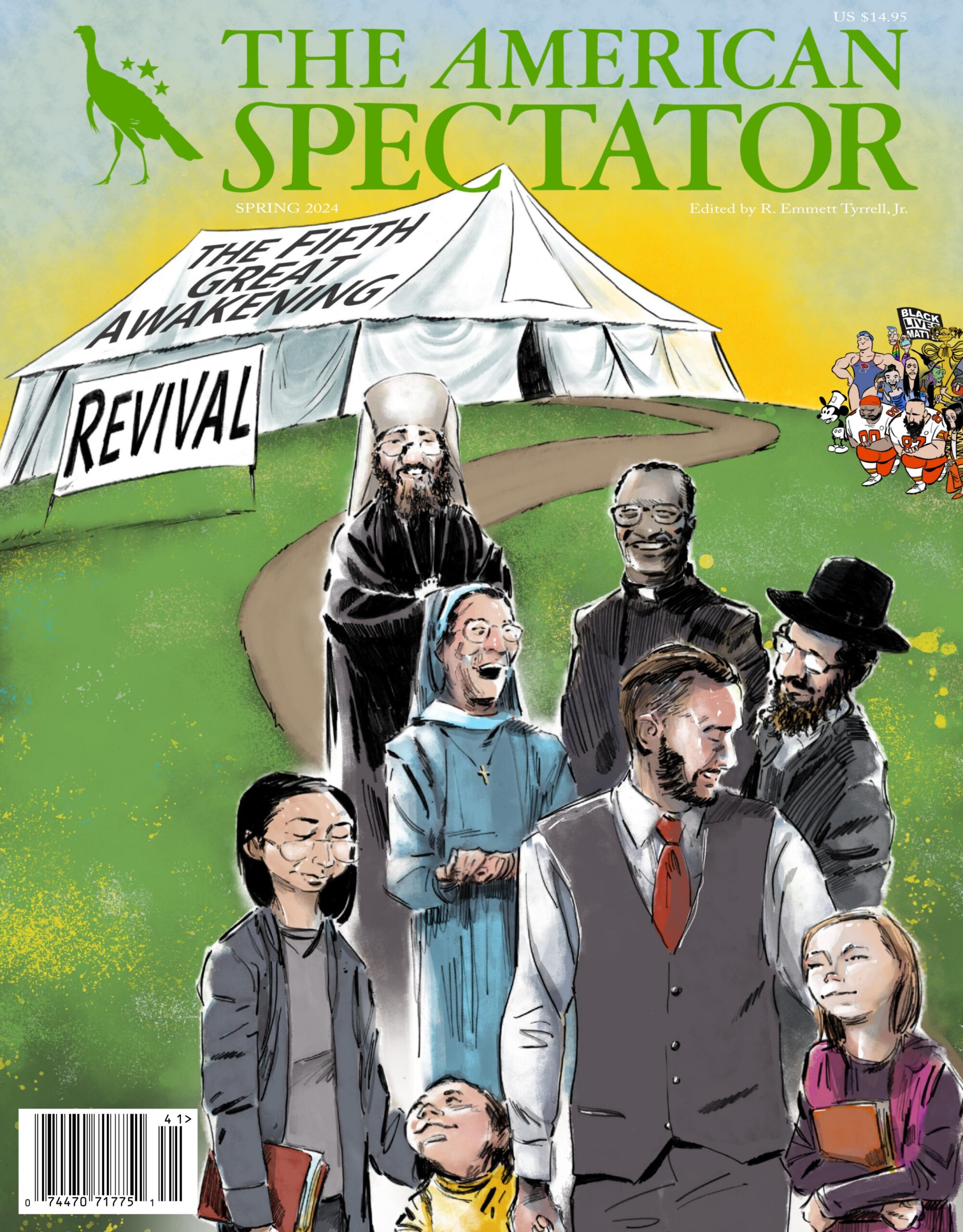

Art by Bill Wilson

Many in the Church felt (and perhaps still feel) that the traditional movement was small and even inconsequential, and, in their eyes, Summorum pontificum made hardly a blip in the path the Church has taken since Vatican II. But to the growing contingent of Catholics who were in the process of rediscovering tradition, including my parents, Summorum pontificum was a lifeline.

I grew up attending Mass from the choir loft. I sang my first Mass at the age of seven — the setting for the ordinaries (Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei) was Mass VIII, or Missa de Angelis (a medieval Gregorian chant) — and began playing the organ for Mass before I was in high school. While my family primarily attended the Latin Mass, I grew up singing for both liturgies; in college, the schola I directed did the same.

A post–Summorum pontificum world made this kind of flexibility possible, and its impact on the liturgy and young Catholics has been undeniable. There has been a welcome revival of traditional music among many young people regardless of which liturgy they attend. At the same time, many young adults in the Catholic Church participate in contemporary praise and worship happily and without restraint.

Young Catholics and families looking for thriving parishes frequently attend Masses (in either English or Latin) where they can find bells, incense, and Gregorian chant. These churches are incubators of orthodoxy: kids scream in the background, families take up entire pews, and the average age of the choir is well below thirty. One wonders if this may have been what the fathers of Vatican II intended when they signed Sacrosanctum concilium, which declares that “the Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as specially suited to the Roman liturgy; therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services.”

Music, and by extension art, is technically not an integral part of the liturgy — but it is a vital aspect of the act of worship and impacts the way we think about our beliefs. As Gregorian chant and more traditional forms of liturgical music, including polyphony, experience a revival, they will undoubtedly shape the way young Catholics see and experience their faith.

What remains to be seen is whether Pope Francis’s 2021 motu proprio (papal decree), Traditionis custodes, will impact the budding revival of ancient liturgical music. While the document does not mention (or even pertain to) sacred music, it severely limits diocesan Tridentine Masses, which could have an impact on the organic rediscovery of more traditional forms of music in parishes where both forms of the Roman liturgy were celebrated.

On the other hand, it may be that it will prove difficult, or even impossible, to return to the Church of the early 2000s. Too many young Catholics have fallen in love with traditional forms of music and culture. They want incense, Gregorian chant, beautiful stained glass, and bells in their churches.

In 2017, the Diocese of Raleigh, North Carolina, dedicated its own brand-new cathedral. From the outside, it looks how one would expect a church to look — it’s shaped like a cross, and a massive dome rises out of its center. Inside, white pillars rise to the ceiling and light streams in through stained glass. The Salve Regina or Anima Christi fits in this space.

As you walk into the Raleigh cathedral, you’re transported out of our increasingly existential and nihilist world. The individual is no longer the center of the universe; he is coming into contact with the Divine.

Subscribe to The American Spectator to receive our latest print magazine on the future of religion in America.

READ MORE:

Those Who Disavow God Entrust Their Faith to Aliens and Bigfoot

The Gospel of Discontent: How Feminism Shattered Our Understanding of Motherhood