McNamara at War: A New History

By Philip Taubman and William Taubman

W. W. Norton & Co., 2025, $39.99

Just when you thought it was safe to go back to the bookstore, here he is again, risen from the ashes — America’s answer to Albert Speer, Robert Strange McNamara. Although this is not the first biography of our defense supremo during the Vietnam War, it is certainly the most complete, based on private family records, correspondence, diaries, and interviews, as well as tape recordings of conversations in the Oval Office. At times, it is painful to read, not only because of the overarching tragedy (not, as McNamara himself would have seen it, of his own life) but rather of the many lives he destroyed in the service of a massive ego.

He combined high intelligence (not to be confused with intellect) with drive and enormous capacity for hard work, which anyone will tell you can often compensate for lots of other deficiencies.

Born in California in 1916 to a middle-aged father and a young, ambitious mother, McNamara excelled at school from a very early age and was driven to succeed at whatever he did. He combined high intelligence (not to be confused with intellect) with drive and enormous capacity for hard work, which anyone will tell you can often compensate for lots of other deficiencies. After completing his bachelor’s at the University of California, Berkeley, he went to Harvard Business School, where he plunged into a new discipline, managerial accounting. After graduation, he worked for Price Waterhouse in San Francisco, but eventually returned to his alma mater to teach. When World War II came along, he was commissioned into a special branch of the service that utilized the new field of statistical analysis. This led him to missions in England and the Far East. When the war ended, like many of his colleagues, he was snapped up by the corporate world, in this case, Ford Motor.

At the time, Ford was in the doldrums, having fallen far behind General Motors after the death of Henry Ford’s son Edsel. McNamara was brought on to turn the company around, and this he did, winning particular acclaim for his relatively young age. He was only 44 years old when President-elect John F. Kennedy persuaded him to leave corporate life to head the Defense Department.

The move to Washington upended not merely McNamara’s career but his lifestyle. Perhaps “upended” is not quite the right word; it revolutionized it. Formerly, he lived a rather wholesome if boring suburban life in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Now, however, he discovered (and was discovered by) the Kennedys and their court. A whole new glamorous lifestyle replete with movie stars and sports figures opened up to him, and he plunged in with enthusiasm. His wife, who was afflicted by bad health most of her adult life, was often at home while her husband enjoyed pool parties and cocktails at the Kennedys’ Virginia estate or at the White House. He became somewhat enamored of President Kennedy as a person, and even more of his wife, Jacqueline. After the President’s assassination, McNamara became even closer to the Widow Kennedy, becoming her very good friend (these last three words deserve capitalization). McNamara was devastated by Kennedy’s assassination, and it took all of President Lyndon Johnson’s legendarily persuasive skills to get him to remain at his department.

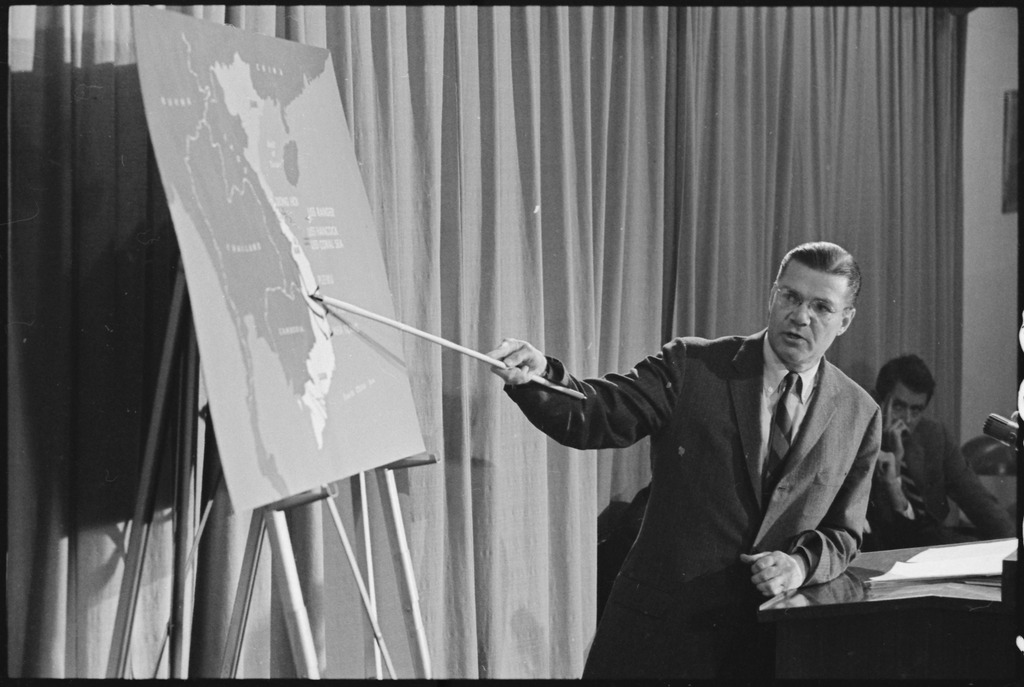

Although his own military training was minimal, McNamara never saw any reason to be the slightest bit intimidated by the brass hats in the Pentagon and brought in his own people, mostly civilians trained in systems analysis. These skills, if one may refer to them as such, were McNamara’s unique contribution to the prosecution of the Vietnam War. U.S. involvement in that country, restricted during the Kennedy years to “advisers” (some 11,000 at the time of the president’s death) burgeoned exponentially, starting in 1965 to more than 550,000 until the day in 1968 that President Johnson refused General William Westmoreland’s request for yet another 206,000 troops, something that would otherwise have required a total mobilization and a massive reserve callup.

In grasping the Vietnamese nettle, President Johnson was faced with an agonizing strategic dilemma. The war was being fought in South Vietnam against an enemy that was just across the border but was receiving weaponry and logistical aid from the Soviets and the Chinese. Mindful of the experience of the Korean War, however, Washington was understandably reluctant to move north of the border between the two Vietnams for fear of provoking a massive Chinese intervention. Nor was it wholly comfortable with bombing civilian targets, inasmuch as it was often difficult to distinguish between them and legitimate military objectives.

This condemned U.S. troops to fight a guerrilla war in very inhospitable conditions — a triple canopy jungle against an enemy with decades of experience in the terrain and the capacity to recruit supporters who were not always easy for American troops to identify. The generals in the Pentagon thought the solution was to bomb North Vietnam more heavily and more intensively, while the U.S. military in-country was constantly lobbying for more ground troops, raising draft calls to record levels and, in time, provoking a massive anti-war movement centered in major cities and university towns.

The result was the worst of all options — bombing North Vietnam sufficiently to create widespread sympathy for that regime in Western Europe and even parts of the United States, without persuading it to desist in its efforts to conquer the south or indeed even to seriously inconvenience them. Moreover, the South Vietnamese state and army were, to put no great gloss on the matter, corrupt and incompetent losers, ready enough to fight — to the last American soldier. (RELATED: Avoiding the McNamara Trap With China)

What is deeply unsettling in this book is how early on McNamara realized this. For two long years — from about 1966 to 1968 — he kept insisting that notable progress was being made on the battlefield, knowing in fact that this was a flat lie. His biographers suggest two reasons for this: He had never faced failure in anything he had ever attempted, and the experience was wholly new to him. And then there was fear of President Johnson, who could intimidate any man, even one as arrogant and self-assured as Robert McNamara.

The problem for McNamara became even more agonizing somewhere in 1967, when the Kennedy family, most notably Senator Robert Kennedy but also Jacqueline Kennedy, privately and then publicly turned against the war. President Johnson loathed Robert Kennedy and indeed the whole Kennedy retinue, who, he rightly suspected, wanted to replace him in the White House. At times, he began to wonder just where McNamara’s ultimate sympathies might lie.

To make a long story short, the tension these dual loyalties provoked led McNamara to have a nervous breakdown. The war also created a crisis with his children and probably also caused the premature death of his long-suffering wife. Before McNamara could go public, however, Johnson offloaded him onto the presidency of the World Bank, where he knew that as an international civil servant, his former defense secretary could be expected to keep silent on political issues. It was only many years later, in a memoir, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (1996), and then in a documentary film, Fog of War (2003), that he admitted “we” (he should have said “I”) “were wrong.” This was presumably intended to spread the guilt more widely, as well as to provide consolation to the families of young men who, unlike Robert McNamara, did not go to Harvard, or, unlike his son, did not go to Stanford* but ended up either dead, disabled, or traumatized by their Vietnam experience.

By this time, McNamara had earned reentry into the clubs and social circles of America’s liberal elite, partly through his mea culpa, partly through his opposition to Reagan’s defense policies, but mainly through his work at the World Bank. The authors of this book, a father-son team — one an academic, the other a New York Times journalist, conventional liberals both — naturally validate this action, since they presumably subscribe to the view that shoveling tax dollars onto Third World tyrants and kleptocrats produces “development” and “poverty alleviation” (just because the functionaries at the Bank say it does).

The story even has a happy ending — for McNamara. He is revered again by the Council on Foreign Relations, the Washington Post, and the New York Times, invited everywhere. He even finds love again with a middle-aged widow and reconciliation with his children. The authors of this book leave it a bit unclear whether McNamara ever actually visited the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington.

Mark Falcoff is resident scholar emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute. He served as a commissioned officer in the US Army, 1963-65.

* It is a matter of considerable interest to note that the sons of field commander General William Westmoreland, Robert McNamara, and Army Secretary Cyrus Vance, though all of appropriate military age, did not serve in the military. The Taubman book explains the clever tricks by which the McNamara family kept their son Craig out of the draft.