The drama behind the selection of the College Football Playoff (CFP) field this year is reducing to a familiar plot point: Should Ohio State be included in the field of the four-team tournament, to be announced Sunday just after noon Eastern?

As Roseanne Roseannadanna could have said about the Buckeyes, “It’s always something.” Since the CFP was installed for the 2014 season, Ohio State has been the chief provocateur in nearly every selection controversy. In 2014, Ohio State entered championship Saturday in fifth place; a 59-0 Big Ten championship game blowout of Wisconsin vaulted them into the final four. In 2016, they made it in even though they did not win a conference championship and didn’t even play in a conference championship game. In 2017, they won the Big Ten title but got passed over on Selection Sunday. In 2018, they won their league with only one loss on the season but got edged out by independent, and undefeated, Notre Dame and one-loss Oklahoma.

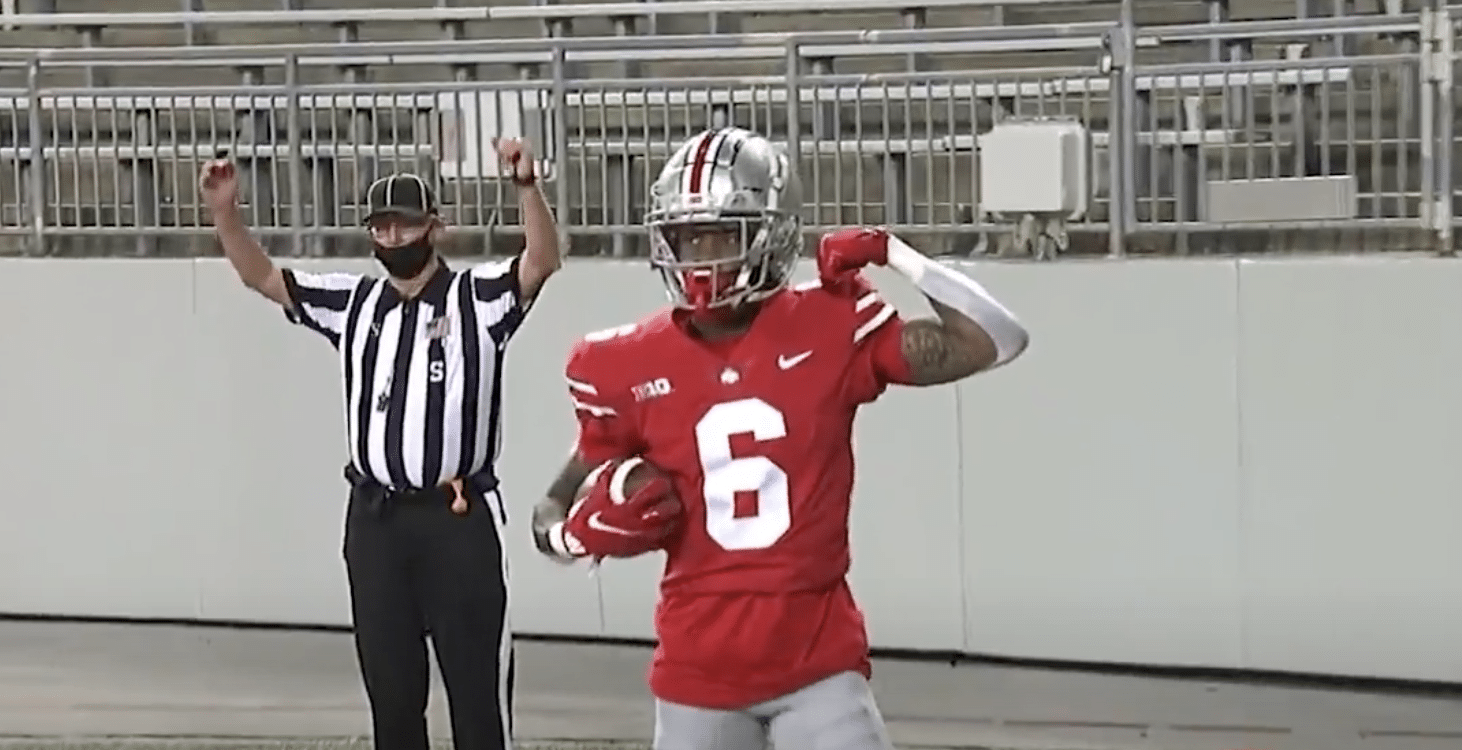

This year’s brouhaha centers on the number of games played. After Saturday’s action, Ohio State will have played six; other worthies will have played as many as 11. Can you legitimately be chosen for a national tournament when you play a little more than half as many games as your competitors?

Obviously, if the Bucks fall to Northwestern in Saturday’s Big Ten championship game, they’re out. But should they win — they’re favored by almost three touchdowns — the argle-bargle will commence forthwith. Notre Dame looks like a lock to make the field, their position jeopardized only if they lose big — 59-0 big — in the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) championship game Saturday. Clemson, their opponent in that game, gets in if they beat Notre Dame and thus reverse the results of their November showdown, which the Irish won. This time, though, the Tigers have the services of their all-star quarterback, Trevor Lawrence, sidelined by COVID for the first contest, which has made them a double-digit favorite. And Alabama is in because … well, they’re Alabama, a bona fide monster brand in the college game. (They’re also undefeated and have blown out everybody they’ve played.)

Naturally, COVID is the big wild card in the playoff selection proceedings.

Who gets the fourth spot? Should Ohio State get in if Florida beats Alabama in the Southeastern Conference (SEC) championship game? Should Texas A&M, who lost to Florida but beat everybody else, make it? Does two-loss Iowa State, if they win the Big 12 championship game, get a look? How about undefeated Cincinnati, the best of the Group of Five schools?

It all depends on the committee. Ah yes, the committee. On Sunday a panel of 13 athletic directors, former coaches, ex-jocks, a onetime sportswriter, and an ex–army chief of staff will throw their knucklebones, so to speak, to determine the four tournament teams and their seedings.

Speculating on what the committee thinks, and why it thinks what it thinks, has become a driving force in sports talk radio, rivaling in airtime discussions about who’s better, LeBron or Michael, what’s wrong with Tiger, and whether Tom Brady is the GOAT (greatest of all time). The committee publish criteria for their selection — factors include strength of schedule, winning a conference championship, a team’s record, the results of head-to-head matchups with other potential entries, and even weather and injuries — but they don’t divulge their reasoning until after they’ve selected the field. What they’re thinking in real time, prior to Selection Sunday, how they’re weighing the criteria, which factors resonate with them and which factors do not, which teams are trending up and which down, can be adumbrated week by week by changes in rankings but is otherwise cryptic, arcane, protected, and about as accessible to your average sports fan as the minutes of a Bilderberg meeting.

It’s a little messy, true, but it’s immeasurably tidier than previous setups. Prior to the CFP, major college football was the only college sport without a national championship tournament or a national end-of-season meeting.

Which made for a lot of championships and a lot of confusion, maybe even chaos. From the game’s invention in 1869 until 1992, no fewer than 38 different entities, by my count, have crowned college football champions. Everybody from panels of sportswriters to councils of coaches to computer gurus and historical researchers to a guy working for a Los Angeles bakery have selected national champions. Frequently dual champions were crowned, often three were named, and in some years in the 1920s and 1930s as many as five or six champions were anointed, but hardly ever did the top two teams duke it out on the field of play.

Only in 1992 did the football cognoscenti get serious about crowning a champion on the field of play. After two attempts at guaranteeing a bona fide one-versus-two final matchup came up short — the Bowl Coalition (1992–94) and the Bowl Alliance (1995–97) — in 1998 college football leaders installed the Bowl Championship Series (BCS). This vehicle, in existence until 2013, managed to get two teams to play for the championship in, for a few years, a major bowl game, rotating among a handful of sites, and then in a dedicated final game after the bowls. Only once during this span did the BCS fail to produce a single champion, in 2003, when the Associated Press and coaches’ poll champion, USC, inscrutably was not invited to the championship game.

Since 2014, the playoffs have been orderly, and the playoff fields predictable. The usual suspects seem to make it into the semis on a yearly basis: in the six years since the CFP started, Alabama and Clemson have been there five times; Oklahoma, four times; Ohio State, three times. Single appearances have been made by Washington, Oregon, Michigan State, Notre Dame, Florida State, and LSU.

But 2020 is the Year of the Virus, and, naturally, COVID is the big wild card in the selection proceedings. Ohio State, having had three games canceled for viral reasons, is competing for a spot in the final four with teams that have played four or five more games. Fewer games mean fewer injuries and less physical wear and tear on the players, and less mental wear and tear on the coaches. Fewer games also mean fewer chances to lose. And even against weak opponents, good teams can lose, and have lost, in the CFP era. Ohio State has. In blowouts. Twice. In 2017, 55-24 to Iowa, and in 2018, 49-20 to, um, Purdue. The former hurt the Buckeyes’ chances to make the playoffs in 2017, the latter killed them in 2018.

But should the Buckeyes suffer because of the hesitation, and poor leadership, of their conference officials? The Big Ten, we recall, wanted to play football in early August, then didn’t want to in mid-August, then wanted to again in mid-September but decided not to start their season until late October, a month after the SEC and six weeks after the ACC and the Big 12 started theirs. They constructed an eight-game season with no bye weeks, and instituted COVID testing protocols more onerous than the southern conferences. How is it Ohio State’s fault they got only six games in?

Whatever the committee decides, wailing and caterwauling will commence just after noon (ET) on Sunday. Maybe it comes from Columbus, or maybe it comes from College Station, Ames, Gainesville, and Cincinnati.

I’m guessing the latter.