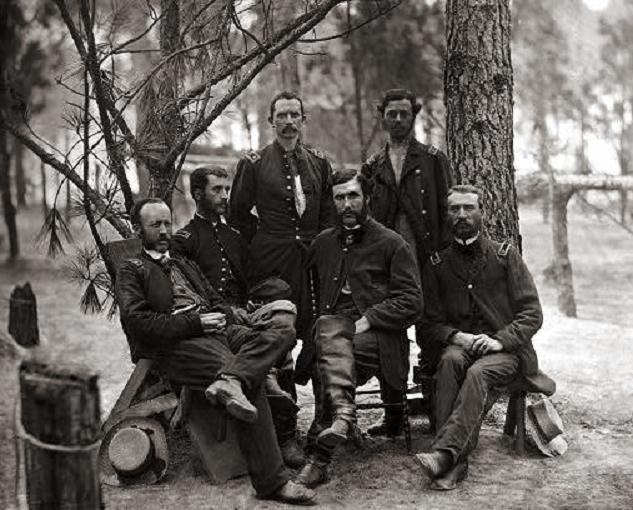

On June 15, 1864 the Army of the Potomac established what became the siege of Petersburg, which acted as the gateway to Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederate States of Virginia. Although the city was not enveloped, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant managed a feat that eluded a succession of eastern Union commanders: he fixed Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in place, preventing any repetition of Lee’s military wizardry evident in such victories as Second Manassas and Chancellorsville. Once the battle became a siege, Lee admitted, the end “will be a mere question of time.”

Yet Petersburg was a relief for brave and capable troops of both sides. President Abraham Lincoln brought Grant east to deal with the South’s only winning army. (Southern forces out west suffered under a gaggle of mediocre generals rather like the blundering Union generals who fought outside Washington; the Confederacy’s only major victory was Chickamauga, the benefits of which Gen. Braxton Bragg promptly squandered.) However, despite possessing overwhelming advantages in manpower and materiel, Grant quickly found that there was no easy way through Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

During the so-called Overland Campaign, which began in the Wilderness in May and concluded with the move on Petersburg, the Army of the Potomac suffered around 55,000 casualties, roughly the size of Lee’s forces and twice the latter’s losses. Cold Harbor, the last battle before Petersburg, was a particularly hideous blunder for Grant; the federals attacked well-entrenched Confederates, suffering about 7,000 men killed or wounded, compared to barely 1,500 southern casualties. Union morale was low even before the disastrous assault: soldiers contemplating the southerners’ fortifications morbidly sewed labels with their names on their uniforms to allow identification of their bodies, an innovation later turned into dog tags.

The seemingly endless casualties lists almost sunk Lincoln’s reelection. After the Wilderness slaughterfest, Sen. Henry Wilson of Massachusetts reflected: “If that scene could have been presented to me before the war, anxious as I was for the preservation of the Union, I should have said: ‘The cost is too great; erring sisters, go in peace.’” Too late, this ardent nationalist was forced to ask, how many lives was political unity worth?

Petersburg offered no magic elixir to repair the public’s disenchantment. Casualties mercifully fell dramatically when sedentary sharp-shooting replaced large-scale assaults, but the conflict stagnated: the Army of the Potomac did not break through until April the following year. Shortly thereafter Lee surrendered, effectively ending the Confederacy’s resistance, though some smaller military commands remained and President Jefferson Davis went on the run.

Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in September did more than anything else to reelect the president in 1864. The conflict’s sacrifice no longer seemed futile. Victory suddenly looked achievable. In fact, the Confederacy’s defeat by then was inevitable, irrespective of Lincoln’s political fate. Even had he lost he would not have surrendered his office until March 4 (later changed to January 20), which would have allowed him to bring the war almost to a close anyway.

The consequences of the conflict were horrendous. Recent scholarship suggests that battle deaths ran as much as 750,000. Overall at least one million Americans are thought to have died. Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced as the South was ravaged, suffering the sort of destruction commonly afflicting combatants in European wars. Agriculture, community, and property were destroyed in the south, while civil liberties and constitutional limits were violated in the north. The impact on the former Confederates was disproportionate: one out of every five military age men was killed, treble the proportion in the North. Union campaigns by Sherman, on his famous “march to the sea,” and Gen. Phil Sheridan, while fighting through the Shenandoah Valley, adopted modern total war techniques to devastate civilian lands and resources. And southerners paid for their reliance on slaves, which reflected a huge share of the South’s wealth, that was wiped away. Today’s massive centralization of national power, intensified in every succeeding crisis, is a tragic testament to the Civil War.

It is said that the victors write the histories and that certainly is the case in the Civil War — more accurately characterized as the War Between the States, since the South sought separation, not domination. Normally a civil war entails a common struggle to control the whole.

Most American history books admit of no doubt regarding the necessity of the conflict, which according to national myth was a harrowing fire through which the country was refined and tempered. It was a grand moral crusade against slavery and the genesis of a beneficent activist national government. Affirmation of the Civil War’s virtues is reflected by the unanimous ranking of Lincoln as America’s greatest president. After ordering the invasion of his onetime countrymen which ended up killing a million Americans.

The question whether the war was justified has been forever overshadowed by the retrospective treatment of the conflict as directed against slavery. It was not. The number of abolitionists was small. Many critics of slavery, like Lincoln, favored colonization, that is, sending freed slaves back to Africa (the genesis of the modern nation of Liberia). The Republican Party campaigned to limit slavery, barring its spread to the territories, not free the slaves. Had the war ended quickly — the likely result, for instance, had Lee accepted command of the Union forces, offered in early 1861 — slavery would have survived, largely undisturbed. Liberation became a war measure; the famed Emancipation Proclamation, purporting to free slaves under enemy control — which it obviously could not do so until they were out of southern control — was only issued on January 1, 1863.

To understand the cause of the conflict one must ask, first, why did the South secede? Second, why did the North stop its brethren from departing?

Whether the southern states had constitutional warrant to secede from the Union is a fascinating intellectual dispute with no accepted answer. In this case force of arms supplied the answer. Nor does it matter much whether the South had a more respectable reason to secede than slavery. Why should Northerners kill former fellow citizens for wanting to leave for whatever reason? It is hard to see why secession warranted war.

Still, slavery was the triggering event. There were other issues, such as tariffs, but none would have animated the white populations to leave the union. Although Lincoln pledged to respect the institution of slavery, it would have become much less secure facing hostile national executive and legislative branches. His election sparked the almost instantaneous walk-out by seven deep South states, starting with South Carolina.

However, eight slave states remained. Had all gone out the North’s task would have been far greater. But the eight remained loyal until Lincoln called up 75,000 militiamen to suppress the rebellion. Notably, this was no campaign to free the slaves. Although the president genuinely loathed slavery, he famously wrote Horace Greeley: “My paramount object in the struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” Lincoln’s overwhelming concern was to preserve the national government; the status of the slave system that so distorted the government was secondary.

Only after the president announced his plan to coerce the seceded states did the upper South — Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia — leave the Union. They were willing to subordinate slavery to national unity but would not join an effort to suppress states with which they had more in common than with most of the North. The border states of Kentucky and Missouri divided and fought their own mini-civil wars, while Union occupation preserved Maryland’s loyalty and tiny Delaware never had a choice. One North Carolina unionist complained: “Union sentiment was largely in the ascendant and gaining strength until Lincoln prostrated us. He could have adopted no policy so effectual to destroy the union.… Lincoln has made us a unit to resist until we repel our invaders or die.”

The issue of coercion was critical to many Americans. Before leaving U.S. army service, Col. Robert E. Lee wrote: “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union.… Still, a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me.” Horace Greeley could have been plagiarizing Lee when the former editorialized in the New York Tribune: “We hope never to live in a republic whereof one section is pinned to the residue by bayonets.”

It is hard to disagree with such sentiments. If Californians today declared that they wanted to separate from the rest of America — perhaps with the enthusiastic encouragement of many conservatives! — should Washington send in the army? Conduct terror bombing from the sky? Set up a naval blockade, an updated “Anaconda Plan” of sorts? Hopefully not. Whether the Golden State’s departure was “legal” would matter little. Washington would have to choose between wishing 40 million Californians well or killing them. The first would be the better option.

Why did Northerners respond differently in 1860? They viewed Southern states, especially South Carolina, as breaking the democratic bargain and refusing to play by the rules when they lost. In his inaugural address Lincoln argued that “the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy” through its rejection of majority rule. In fact, he was spinning: the South rejected not majority (of white men, of course, in both sections) rule, but national majority rule. There was no anarchy: secessionists bypassed the radical “fire-eaters,” replicating established institutions and leaders, including most of the federal Constitution. And even if southerners were heading toward “anarchy or despotism,” as the president argued, was that a good reason to lay waste to their homes, families, communities, and states?

Some in the North feared that the Confederacy would close the Mississippi. A few nationalists worried that a passive response to Southern secession would tempt other sections of the nation, such as the northwest, to secede. A number of abolitionists saw a chance to end slavery, though others were pacifists.

Perhaps most important was raw nationalism, the belief that the American nation was indivisible and would inevitably overspread the entire continent, the malignant doctrine of Manifest Destiny. Lincoln spoke of “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land.” Eloquent sentiments to be sure, but no justification for war — thereby creating more battlefields and graves to be connected by nightmares of fighting each other. How could the Union be such a good institution if only “maintained by swords and bayonets”?

Unfortunately, far too many people imagined that resolution of the dispute wouldn’t require many swords or bayonets, that victory would come easily. A few shots would be fired and the cowardly Yankee shopkeepers would flee north or the cowardly secessionist blowhards would fade away.

South Carolina committed an act of war by firing on Fort Sumter, but there was no need to open general hostilities in response to such a limited act. However, Lincoln left the indefensible U.S. garrison in place, inviting such an incident. That probably was his intent, since he carefully calculated all his policies. The Sumter attack galvanized support for raising troops for coercion, which he desired. Although Fort Sumter did not cause the states to fight, it greatly aided Lincoln’s ability to invade the South to suppress secession.

Much of the enthusiasm for war on both sides reflected tragic illusions about the conflict’s consequences. Both Lee and Sherman foresaw a long, bloody war, but they were in the decided minority. Sen. James Chestnut of South Carolina, for one, offered to drink all the blood that would be shed as a result of secession. Soon oceans of blood were spilled in individual battles consuming more lives than all of America’s previous wars together. Americans learned their mistake, but too late. Wilson was not alone in wishing he could roll back time.

There was one, huge, initially unintended benefit from the war — the destruction of slavery. One can admire the heroic struggle against long odds undertaken by Confederates, but the South was no beau ideal of a good civilization. Slavery was brutal, immoral, dehumanizing, and corrosive. The seeming gentility of the South was built atop stolen humanity, dignity, and labor. The system’s destruction was long overdue.

However, only one other slave society eliminated the odious practice through war, Haiti. Everywhere else the practice was peacefully abandoned. For instance, Brazil lagged behind the U.S. in emancipation, but eventually acted without its national government killing anyone, let alone a million people. Moreover, through “Redemption” white southerners reimposed white supremacist rule. This blight on American society survived for decades, leaving ill effects that persist today. Peaceful separation in 1861 conceivably could have resulted in justice for African-Americans sooner than did coercive union.

Most important, when it comes to secession, the one and most obviously beneficial outcome of the war was actually unplanned. At the outset abolition was rejected by almost everyone, north and south. Preserving the Union simply wasn’t a moral cause. It didn’t warrant mass slaughter.

In June 1864 the ultimate denouement of the Civil War approached. Once the Confederacy’s most effective army and talented general were stuck defending Petersburg, defeat was inevitable. Soon racial problems and conflict would shift back to the political realm. There never was any adequate justification for either secession or coercion, which together tragically turned northern Virginia into an open air abattoir in Spring 1864.

Doug Bandow is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute and the author of The Politics of Plunder: Misgovernment in Washington and The Politics of Envy: Statism as Theology, both published by Transaction.