Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought the Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, and Remade America

by Fergus M. Bordewich

(Knopf, 480 pages, $32.50)

Most Civil War students realize that Congress was ahead of President Lincoln on matters such as slave emancipation and the punishment of Southern whites. Biographers usually attribute Lincoln’s lag to his appreciation for coupled considerations, minimized by his critics. He recognized, for example, that hasty emancipation and retribution against Southern civilians might drive the border states into the Confederacy, making the war unwinnable. In contrast, congressional Republicans such as Sen. William Fessenden and Radicals like Rep. Thaddeus Stevens and Sen. Benjamin Wade focused on provincial interests and their supposed moral convictions.

When Wade became dissatisfied with the slow progress of Gen. George McClellan’s Union Army, for example, he demanded that the president fire its commander. After Lincoln asked Wade who should replace McClellan, the senator said, “Why, anybody!” Lincoln replied, “Wade, anybody will do for you, but I must have somebody.”[1]

As its title indicates, Fergus Bordewich’s Congress at War tells the story of Civil War legislation from the congressional perspective. The author concludes that Congress’s vision of postbellum America was superior to Lincoln’s. Their higher morality, Bordewich implies, required that they drag the president forward.

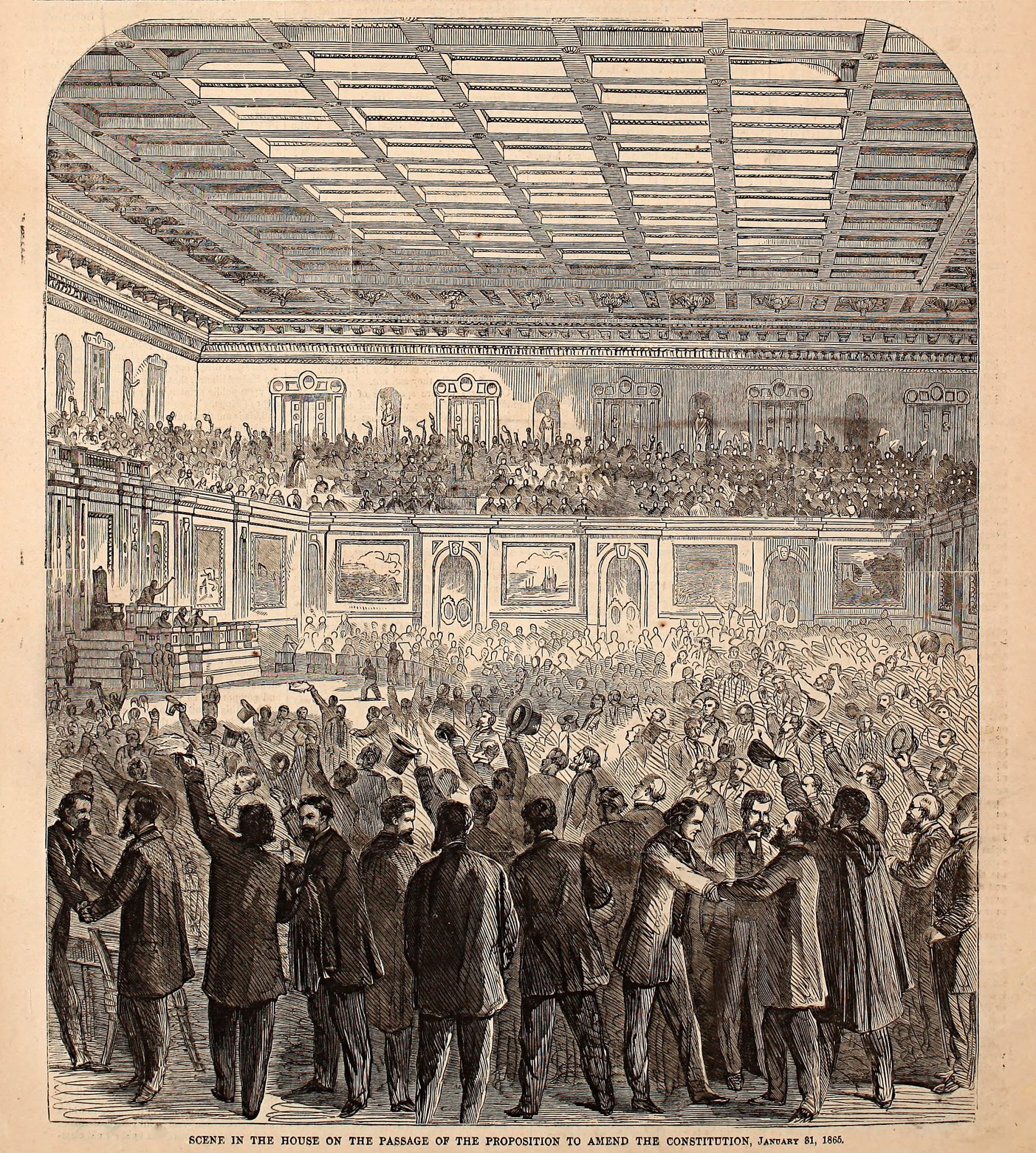

To be sure, legislation and acts such as the Pacific Railroad, Western Homestead, Legal Tender, National Banking, the 13th Amendment, and land-grant colleges undeniably transformed America. The Pacific Railroad connected the West Coast with the eastern half of the country, while the Homestead Act helped settle the land in between. The Legal Tender and National Banking acts authorized a national currency and forever allied the bankers with the U.S. Treasury. The 13th Amendment ended slavery, and land-grant colleges pioneered our modern state university systems. Although Congress instigated some, other initiatives were existing Republican policies, as evidenced by the Homestead and Pacific Railroad planks in the 1860 party platform. Moreover, far from foot-dragging on the 13th Amendment, Lincoln championed it.

Similarly, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase was more involved with the Legal Tender Act than anyone in Congress. In fact, Sen. Fessenden of the Finance Committee opposed it as unconstitutional and reckless. But Chase could not finance the war without it, even though the resulting Greenbacks could not be redeemed for specie (gold and silver coins), as was previously mandatory for reliable paper money. In order to encourage their public acceptance, Chase proposed adding the “In God We Trust” slogan to the bills as he had done earlier for coins. But Lincoln suggested wryly, “If you are going to put a legend on the Greenbacks, I would suggest that of Peter and John, ‘Silver and gold I have none, but such as I have I give to thee.’ ”[2]

Notwithstanding his 1862 Emancipation Proclamation and active promotion of the 13th Amendment, Radical congressional Republicans grew increasingly impatient with Lincoln. They particularly objected to his “lenient” Reconstruction terms. While the war was still in progress, in December 1863 he issued a proclamation to readmit any Southern state that would outlaw slavery and declare allegiance to the United States. Within five months, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee complied. But since the new state governments were formed by electorates that totaled a threshold as low as 10 percent of the 1860 voters, Congress objected. They did not appreciate that Lincoln intended for the low threshold to encourage Southern states to abandon the Confederacy. Instead, they interpreted the plan as a defiance of Congress. “The authority of Congress is paramount,” wrote Sen. Wade, “and must be respected.” After the war had ended, in December 1865 Congress refused to seat any of the South’s elected representatives.

Instead they demanded universal black suffrage in the South while exempting the North: “Without [Southern black] votes,” wrote Sen. Charles Sumner, “we cannot establish stable governments in the rebel states…. Mr. Lincoln is slow in accepting truths.” While Bordewich attributes the demand to a noble impulse for racial equality, the bulk of the evidence indicates that congressional Republicans chiefly wanted to retain political power.

After the Confederate surrender, the party was barely 10 years old. Its Radical wing worried that it might be strangled in its cradle if readmittance of Southern states failed to be managed in a way that would prevent Southerners from allying with Northern Democrats to regain control of the federal government. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, who led the committee formulating congressional Reconstruction, admitted that Southern black suffrage “would insure the ascendancy of the [Republican] party.”

Despite being a war hero, Republican Ulysses S. Grant won his first postwar presidency by a narrow 53-to-47 percent popular vote margin. It was entirely due to Southern black votes, previously enabled by congressional Republican legislation. Even though many ex-Confederates were not allowed to vote, Grant won only a minority of America’s white votes. Moreover, his seemingly decisive 241-to-80 electoral college victory was tenuous. In combination with disfranchisement of former Confederates in Tennessee, Missouri, and West Virginia, ex-slaves gave Grant 67 of his 214 electoral votes. Without those 67 votes, the election would have been a tie.[3]

While the transformative legislation of the 36th and 37th Congresses might have failed to pass if Southerners held onto their seats by declining to secede, their opposition was not the mere “intransigence” Bordewich claims. In fact, the Southern Democratic 1860 party platform also included a Pacific Railroad plank. They just wanted a Southern route, which would have avoided the expensive tunneling through the Sierra Nevada range that resulted from the Pacific Railroad Acts.

More broadly, however, Southerners had long opposed public land subsidies due to their potential to foster crony capitalism. They similarly opposed bills that would increase the central government’s power. The Pacific Acts’ transcontinental line formed by the Central Pacific (CP) and Union Pacific (UP) was financed with gigantic federal land and bond subsidies. Although teetering on bankruptcy just three years after completion in 1869, owners of the Central and Union Pacific already had siphoned off nearly all of the subsidies to companies that constructed the lines. Together with selected congressmen, the CP and UP shareholders owned the construction companies that built the railroads and thereby earned monopolistic profits for doing so. In 1873, the Northern Pacific Railroad, owned by the biggest Civil War Treasury Bond underwriter, declared bankruptcy after receiving federal acreage grants nearly as large as the state of Missouri.[4]

Railroads and other consolidators exploited the Homestead Act. Although putatively crafted to provide cheap land for small farmers, consolidators often purchased lands from homesteaders at cut-rate prices. The bargain prices mandated for homesteaders enabled them to realize substantial percentage gains by quickly reselling newly acquired tracts to consolidators, then staking another claim and repeating the process. Less than 20 percent of the land put under cultivation between 1860 and 1900 was taken up under the 1862 Homestead Act.[5]

While the National Banking Act promoted a uniform currency, it also formed a dubious alliance between banks and the U.S. Treasury. Specifically, it created a ready market for Treasury bonds by permitting national banks to substitute them for gold as a monetary reserve. Since gold paid no interest, the banks eagerly bought new interest-paying treasury issues to use as reserves. The alliance continues fueling national debt growth to this day.

Finally, Bordewich hardly mentions the Morrill Tariffs, which enlarged the dutiable items list and increased their rates from 19 percent before the Civil War to an average of 45 percent for the next 50 years. Although beneficial to Northern manufacturers, the protective tariffs were doubly injurious to the South’s export economy. First, they prevented less-costly imports from entering the U.S. market. In 1866, for example, railroad iron sold for $32 a ton in London and $80 in New York. Second, they motivated Europeans to seek cotton supplies from countries that would more readily buy European imported manufactured goods. Since Europe was the South’s biggest cotton buyer, the postwar era of high tariffs fostered long-term poverty among Southern blacks and whites.[6]

Congress at War is an engaging analysis of Congress’s role in the landmark legislation of the Civil War period. While commendable for telling a little-known story, the book suffers from a zeitgeist that hallows era-specific Republicans while misrepresenting Southern “intransigence” by omitting explanatory facts.

—

[1] Stephen Sears, Lincoln’s Lieutenants, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2017), 154

[2] Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: Vol. II (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1939), 660

[3] Albert Castel, Andrew Johnson, (Lawrence: Kansas University Press, 1979), 208

[4] Carlos A. Schwantes, The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History, (Lincoln, Ne.: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 173

[5] Ludwell Johnson, Division and Reunion, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1978), 111

[6] Ira Tarbell, The Tariff in our Times, (Norwood, Mass.: Macmillan, 1911), 31

Philip Leigh has written six books on the Civil War and Reconstruction, including U. S. Grant’s Failed Presidency and Southern Reconstruction.