I

In a dimly lit corner of Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum, amidst an impressive array of Buddhist art bequeathed to the institution by the tobacco heiress Doris Duke, there is one sculpture that stands out above all the rest: a Ming-era dry-lacquer sculpture of the bodhisattva Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy, the Barque of Salvation, and the Perceiver of the World’s Lamentations. In the Mahayana tradition, it was Guanyin who composed the beloved Sutra on the Heart of the Transcendent and Victorious Perfection of Wisdom, and it is believed that this selfsame goddess takes hold of those who have perished, folds them into the heart of a lotus, and gently conveys them to the Pure Lands. Thus does Guanyin serve as a “guide for souls,” and as an object of veneration for those in need of compassion and providential care throughout the Buddhist world.

Perched comfortably on her plinth, the Walters Guanyin projects an outward expression of inward confidence and tranquility. Everything about the sculpture is serene and fluid, in keeping with the bodhisattva’s traditional associations with all things lunar, liquid, impermanent, and in flux. Even the technique used in its creation plays with the notion of transience. The unknown fifteenth-century sculptor responsible for this masterpiece began by fashioning a clay figure, which he then coated with strips of cloth soaked in lacquer, a process akin to papier-mâché. The lacquer was left to harden, whereupon the surface was carefully painted and decorated with gold leaf. Finally, after the clay interior was broken up and removed, the innards were smeared with a pigment containing cinnabar, a deadly toxin that here serves a preservative function. In this way perishable linen, tree resin, and dyestuffs were transmuted into the enduring memorial that awaits sharp-eyed visitors to the Walters.

Looking at this representation of Guanyin, with its noble aspect, fine features, and melancholy patina laid down by time and wear, I am reminded of the lines in Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Notturno that describe

le note rotte del nero

e vermiglio canto avvenire

la melodia dell’eternità

l’inno profondo, sempre più profondo della doglia infinita

the broken notes of black

and vermilion, song of the future the melody of eternity

the deep and ever deeper hymn

of infinite sorrow

Guanyin, attuned as she is to the sounds of the world’s lamentations, would no doubt recognize this refrain, though her own compositions are thought to be rather sweeter. The Precious Scroll of Fragrant Mountain tells of Guanyin’s visit to Naraka, the hell-realm of the dead, where she played joyous music and conjured fields of flowers into bloom. It was said that her mere presence in hell transformed it into a veritable paradise, and for the sympathetic viewer of the Walters Bodhisattva Guanyin, Accession No. 25.256, this seems altogether plausible.

Walters Bodhisattva Guanyin, Accession No. 25.256, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland

Though undoubtedly an artistic triumph, there remains something amiss about this sculpture, at least in its present context. Guanyin really should not be atop so stark a plinth, shoved into the corner of an unadorned and cramped gallery, staring down at a patch of nylon carpeting. In situ, she would have been seated on a rocky throne representing the shores of the island of Mount Putuo, with her gaze directed towards a moonlit pool, as candles flickered in her eyes and wisps of incense smoke danced about her figure. Here she is left unattended by her usual companions, the acolytes Longnü, Shancai, and the Filial Parrot. Her traditional willow branch and her jar brimming with pure water are likewise nowhere to be found. No longer does she serve as a focus of reverence, or as a vigilant guardian of a temple complex and of the Buddhist faith as a whole. Instead she is the trophy of a billionaire heiress, living on merely as an object of curiosity and aesthetic interest. But at least she is fundamentally safe and sound, in the caring hands of the museum’s conservators. The same cannot be said of a great many of the other statues of the Goddess of Mercy, which remained in China, where cultural cleansing and militant atheism have taken a terrific toll on the tangible and intangible manifestations of Buddhism and other faiths besides.

II

One of the best-known representations of Guanyin can be found near the old Qing mountain resort of Jehol. There, inside the Puning Si, the “Temple of Universal Peace,” is an imposing version of the bodhisattva in the guise of “the one with a thousand arms and a thousand eyes.” Weighing in at more than a hundred tons and rising to a height of seventy-three feet, it is considered the tallest wooden statue in the world, and has little in common stylistically with the diaphanous Guanyin on display in Baltimore. Visitors are drawn to the Puning Si by the thousands to visit this staggering work of art, which positively exudes majesty, warmth, and repose, but there is a much darker side to this locale, one seldom dwelt upon by tourists. The temple, as it happens, was built in 1755 to commemorate the Qianlong Emperor’s victory over the nomadic empire of the Zunghars. Puning Si’s Guanyin therefore functions as monumental Manchu propaganda, with Qianlong likening himself to the Goddess of Mercy, the all-seeing and far-reaching source of universal tranquility, as demonstrated by his successful conquest of Xinjiang.

One can get a much better sense of historical perspective by crossing the Wulie River and hiking up the hill to the Anyuan Miao, the “Temple of Pacifying Distant Lands,” a destination rather less popular with tourists than the Puning Si. Intrepid visitants will find, as Anne Chayet has described it, a “complex system of enclosures” with “walls consisting of wood panels richly decorated with paintings, and a classical tianjing [well of heaven] coffered ceiling.” Anyuan Miao is admittedly a somewhat dilapidated place, at least in comparison with the rest of the Eight Outer Temples of Jehol, but a couple of details warrant our attention. The first is the looming presence inside the temple of a large statue of Vajrabhairava, the lord of death, embracing his consort. It is an image quite at odds with that of Guanyin back at Puning Si, and intentionally so. When luxuriating in the empire’s repose, Qianlong could be as sweet as Guanyin, but when pacifying distant tribes he could be as wrathful as death itself. The second detail worthy of our consideration is the fact that the structure itself is not based on an original design; rather, it is an ersatz replica of the great temple of the Zunghars that once graced the city of Kulja, in what is now called Xinjiang.

It was the great Zunghar warlord Galdan Tsering who founded the Kulja Temple, an architectural marvel wherein, according to the Qing official Fuheng’s Imperially Commissioned Illustrated Geography of the Western Regions,

the rooms were of white felt, the walls were of wood; later tiles of gold covered the beams and rafters…. They were so tall that they caressed the skies, gold streamers dazzled the sun, the beams and rafters were immense and the Buddhas were solemn and imposing. Monks were assembled to live in [the temple]… in the evening they beat the drums and in the morning they sounded the conch shells and the chanting of the Buddhist prayers was exquisite.

The military governor Song Yun later observed that “at new year and midsummer the worshippers gathered from far and near, often they brought precious jewels to donate and bestowed gold and silver to adorn the temples” of Zungharia. The city of Kulja, named after a Mongol word for mountain goat (guldja), thereby earned its alternate appellation, Ili-balik, or “resplendent city.” That resplendence came to a definitive end in 1756, when Qing forces again swept into the Ili valley and set the Kulja Temple ablaze. The age-blackened rafters collapsed, the white felt burned away, the gold tiles melted, and the wooden statues of bodhisattvas inside were reduced to ash.

The Kulja Temple was far from the only casualty of Qianlong’s remorseless “war of annihilation” (yongjue genchu) and “extermination” (jiao) against the Zunghars. The human toll was grievous. Wei Yuan, in his account of the Qing invasion, Shengwuji, estimated that of the six hundred thousand Zunghars alive in 1755, “40 percent died of smallpox, 20 percent fled to the Russians or Kazakhs, and 30 percent were killed by the Great Army. [The remaining] women and children were given as [servants] to others.” It was recorded that “for several thousand li there was not one single Zungharian tent,” and that “all remote mountains and water margins, wherever one could hunt or fish a living thing, were scoured out, leaving no traces,” so that “there was not a trace of a living thing, whether grass, bird, or animal.” A “righteous extermination” (zhengjiao) had established Chinese suzerainty over a land that was renamed Xinjiang, the “new dominion.” It hardly seems coincidental that one Chinese term recurs time and again throughout the Qing archival material pertaining to the western conquests: ping, which may mean to “make peace” (heping), but may also signify flattening out or creating a plain (pingyuan). This was a social, political, and cultural demolition job on an imperial scale, in which, as the Qianlong Emperor insisted, “all must be entirely swept away [qiongjiu saochu].”

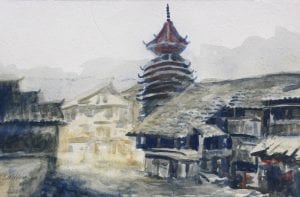

Bill Wilson Studio

What was left of the Zunghars after their extermination at the hands of the Manchu remains as illusory as a steppe mirage. In Qing records we find mention of “nearly 100,000 men drawing bows, and herds filling the valleys,” herds large enough to accommodate regular dispatches of ten thousand head of horse and camel destined for China, either in tribute or in exchange for luxury goods like tea, silk, rhubarb, and earthenware. In Russian accounts like that of the explorer Ivan Unkovsky, we encounter a very different and less purely nomadic view of the Zunghar realm, where “farmers were widespread,” where “special attention was paid to dividing the land into fields,” and where “wheat, barley, millet, pumpkins, melons, grapes, apricots, and apples” were bountiful. The region was rich in iron, copper, silver, aluminum, and sulphur, and the Zunghars were able to produce a ready supply of firearms, both hand-held and camel-mounted. In this they were aided by the Swede Johan Gustaf Renat, a prisoner of the Russians who in turn fell into the nomads’ hands, and who spent the years from 1716 to 1733 teaching his captors the art of cannon-casting and the printing press. All this we know from the scattered accounts of outsiders, but lost today are the lyric and epic poems of the Zunghars, the maxims and proverbs, the legal “mountain writings” carved in red on craggy eminences for all to see and heed. Lost are the uruds tasked with forging weapons and utensils, the kötöchinars who erected yurts for the khan, and the altachins charged with the production of golden sculptures of the Buddha. And lost is the Kulja Temple, a victim of the Qianlong Emperor’s campaign of physical and cultural genocide against Zungharia.

Such modern terms are not wholly out of place here. In 1984, the eminent Chinese historian of the Qing, Dai Yi, admitted that the “Zunghar people suffered a severe disaster. We must expose and criticize the Qing government for adopting such cruel methods,” regardless of whether or not they were adopted in the supposed interests of the “progress of history.” Western historians have been willing to go much further. The Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity included the extirpation of the Zunghars in its list of historical ethnocides, Peter Perdue dubbed the conquest a “final solution,” and Charles Bawden has similarly referred to the “genocide” in which the Qing “indulged.” Mark Levene, for his part, has called the Qing campaign “arguably the eighteenth century genocide par excellence,” but further noted that the “Dzungar extermination might deserve to be treated as seminal,” but “because it has no place — or indeed value — within a Western frame of reference, even arguably a genocide-focused one, its marginalization, or more accurately mental obliteration down a giant memory hole, is likely to be perpetuated into the foreseeable future.”

There is really only one vestige of tangible Zunghar heritage that has escaped that memory hole, and it is the reproduction of the Kulja Temple at Anyuan Miao. Whether the structure was meant as a “religious conservatory for the pious Mongol vassals of the emperor” who had been resettled near Jehol, as Anne Chayet has suggested, or whether it was a “trap set by Manchu imperial hunters to capture and subject the Tibetan church,” as Philippe Forêt has countered, it is surely one of the most peculiar religious sites in the world. The Qing recreation of the Kulja Temple, destroyed by the Qing themselves in a genocidal war against the nomads who built the original structure, constitutes a meticulous act of cultural heritage preservation undertaken in the midst of a relentless program of ethnic extermination. It would almost be akin to a synagogue carefully reconstructed by Albert Speer, or a Incan stone intihuatana lovingly maintained in Hapsburg Toledo.

We cannot be sure if the construction of the Anyuan Miao was intended to be an act of penance or an addition to some kind of cultural zoological garden, just as we cannot be sure whether the black tiles of the temple’s gambrel roof, which represent water, are a delicate reference to the fate of the previous incarnation of the structure in Xinjiang, or are simply faithful to the original and thus an instance of cruel historical irony. We have reason to question Qianlong’s good faith, given that the Jinchuan hill peoples of western Sichuan were likewise targeted for extermination during an outburst of Manchu violence that took place between 1771 and 1776, leading to more genocide, enslavement, and the eradication of the traditional Bon faith in favor of Yellow Sect Buddhism. The Zunghars were far from alone in their fate. What we can be sure of is that, spiritually at least, the Anyuan Miao seems much farther away from the Puning Si than the two miles or so that separate them.

The fate of the Kulja Temple and the Zunghars who worshiped there should not be considered a matter of merely historical or antiquarian interest, for a direct line can be traced from the events of Xinjiang in the eighteenth century to those of our own era. Today, in East Turkestan, hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs have been subjected to a “righteous extermination” not unlike that experienced by the Zunghars, marked by mass incarceration, organ harvesting, the demolition of mosques and graveyards, prohibition of ancestral tongues, and more, leading the China Tribunal, in a final report published in the summer of 2019, to find “unmatched wickedness even compared — on a death for death basis — with the killings by mass crimes committed in the last century.” And whereas the Qianlong Emperor was deeply concerned with the numinous, and was torn between his split spiritual personalities — Guanyin with her willow branch and goblet versus Vajrabhairava with his curved sword and blood-filled skull-cup — the present-day Chinese Communist Party(CCP) has no such curb on its brutality. Totally in thrall to what G. K. Chesterton called the “universal negative” of scientific atheism, the party has embarked on a campaign of iconoclasm utterly appalling to human sensibility, one which would have caused the cheeks of even the most brutal Manchu conqueror to blanch with horror.

III

A story has come down to us from the early days of the Han dynasty, one which tells of a man found to have taken a handful of earth from an imperial tumulus mound. The police apprehended the brazen individual and promptly put him to death, but when the emperor heard of the incident, he reacted with fury at the lightness of the punishment that had been meted out. We can only presume that the vandal had been summarily beheaded or strangled instead of being boiled alive, quartered, pulled apart by chariots, or slow-sliced into bloody ribbons, which presumably would have been more appropriate penalties for such a pu-tao, or “impious crime.” One gets the distinct sense that the preservation of China’s imperial cultural heritage was a matter of considerable importance, particularly in a society wholly devoted to ancestral worship.

“Culture itself is conservative,” wrote the great Chinese scholar and diplomat Hu Shih (1891–1962), and he posited that “there is always a limit to violent change in the various spheres of culture, namely, that it can never completely wipe out the conservative nature of an indigenous culture.” Hu was writing in the mid-1930s, and he could not have foreseen the simple but decidedly sinister solution that Mao Zedong and his fellow communist revolutionaries would devise to address the essential conservatism of Chinese society: the wholesale spoliation, root and branch, of five thousand years of Chinese culture, thought, religion, and tradition. In this way would Hu’s optimistic theory of cultural resilience be sorely put to the test.

Bill Wilson Studio

The merciless Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was aimed at scouring away the ancient patina formed by the “Four Olds” — habits, ideas, customs, and culture — the better to “completely break up with conventional ideas.” This would pave the way for what Mao promised would be “a future of incomparable brightness and splendor,” a veritable ta-t’ung, the long sought-after era of “great harmony.” Maurice Meisner described it rather more aptly as a “strange negative utopianism.” Whereas the Chinese had once ritually swept their ancestors’ tombs, they now set about sweeping their ancestors’ tombs away. The old Summer Palace was slashed at by Red Guards, the Garden of Abundant Nourishment was torn up, murals were defaced, and ancient structures were torn down all over the country. In Beijing alone, 4,922 of 6,843 registered cultural relics were obliterated. The situation devolved to the point where, as Hung Wu later lamented, “the common mind could hardly understand the reason for this massive destruction: the land freed from these ancient buildings seemed incommensurate with the energy and manpower wasted in the project.” But the energy was not, from the Maoist perspective, being wasted in the slightest. The widespread ruination was intended to leave nothing against which the new communist dystopia, which wound up costing as many as eighty million lives, could be measured.

Thoroughly suffused with the perverse spirit of Ludwig Feuerbach and Karl Marx’s “religion of humanity,” the communist authorities similarly threw themselves into a “great leap forward in religious affairs,” with the ultimate goal of “eliminating religion” altogether. So-called scientific atheism quickly gave way to its militant offshoot. Over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, some 90 percent of Chinese temples and churches were “donated” to the communist brigades, while at sites like Daluo Mountain Buddhist monks and nuns were forced to destroy statues of the Buddha and abandon their vows. As Fenggang Yang summarized it, “Folk religious practices, considered feudalist superstitions, were vigorously suppressed; cultic or heterodox sects, regarded as reactionary organisations, were resolutely banned; foreign missionaries, considered part of Western imperialism, were expelled…. The criticism of theism quickly became in practice the theoretical declaration for … eliminating religion in society.” Those who openly identified as believers were ridiculed, curiously enough, as “ox-monsters” and “snake-demons,” while the forces of counter-revolution were referred to as “ghosts, demons, and monsters.” Rhetoric like this suggests the stubborn persistence of certain folk beliefs, as does the common practice of dancing, swearing oaths, and confessing to ideological sins in the presence of effigies of Chairman Mao, who was reverentially referred to as hong taiyang, the “Red Sun.”

The oral testimony of the townsfolk of Ku Village in Guangdong Province, as recorded by the anthropologist Hok Bun Ku, offers a riveting account of the ensuing struggle between the devoted adherents to Buddhism and their secular persecutors. During the Maoist campaign of “doing away with superstitions and blind faith,” the Red Guard “came to our village,” recounted a woman by the name of Qiying, “to destroy the Guanyin temple.” The soldiers “destroyed the painted clay Guanyin sculpture and temple wall with sledgehammers,” and upon completing their task “sang revolutionary songs and left.” Qiying continued,

I was really scared and hastened home because I had a small clay statue of Guanyin in my house. I tried to find a safe place to hide it. In the end, I hid it beneath my bed. In the important festivals, we still worshipped Guanyin, of course we carried it out secretly. Every time I had to close all the windows and the door. My mother-in-law would guard the gate ( bamen). If the situation proved unfavorable, she would knock on the door and I would quickly stop worship and hide everything under the bed. Every time we could only offer food, but not incense, candles, and paper money because the smoke would attract attention.

In such a fashion did Buddhism, along with Taoism, Christianity, and folk religious practices, survive until the Deng era, when, as Hok Bun Ku put it, “the discrediting of the party and many of its institutions” allowed for “a rapid resurgence of local cults.”

By the 1990s, a veritable wenhua re, a “culture fever,” had taken hold, perhaps as a form of transference after the crushing of the 1989 democracy movement. In the early years of the twenty-first century, a religious revival of sorts was in the offing, as Ian Johnson described in his recent book The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao. A 2005 survey found that there were around three hundred million Chinese people identifying as religious (in a population of over 1.3 billion). But a Pew Research Survey suggests that number may be low, as it found 245 million Buddhists alone, and there is data indicating that some 173 million more engage in Taoist practices, alongside fifty-four million Christians, twenty million or so Muslims, seventy million Falun Gong practitioners (at least at the movement’s height), and so on. More abstractly, a 2007 survey showed that 77 percent of Chinese respondents believed in moral causality, 44 percent believed that “life and death depends on the will of heaven,” and 25 percent had actually “experienced the intervention of a Buddha (fo) in their lives in the past twelve months.”

All of this prompted an equal and opposite reaction, in the form of a backlash on the part of the ruling Communist Party, which for its own part has banned its ninety million members from belonging to religious communities of any kind. The State Administration of Religious Affairs has worked to make religious licensing difficult if not impossible. Laws passed in late December 2019 have targeted unregistered Christian churches, in a bid to force Catholic congregations to join the heavily regulated Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, and for Protestant churches to be absorbed by the Three-Self Patriotic Movement. Religious practices and sites are being systematically “sinicized,” and thereby subordinated to the party and its socialist program, at least when they are not being effaced entirely. The aforementioned case of the Uyghurs is only the most notorious of such examples. Hui Muslims have likewise faced persecution, with their Dongsheng Mosque being “sinicized,” schools being shuttered, and Arabic texts purged. A Catholic pilgrimage site, the Shrine of Our Lady of Seven Sorrows, was demolished in October 2019 on the grounds that “it had too many crosses and statues,” while the Gate of Heaven on the Seven Sorrows Mountain was torn down on the spurious basis that it was “dangerous” to use.

Surely the most absurd instance of “sinicization” must be the CCP’s decision in spring 2019 to decapitate the statue of the First Guanyin of Shandong and replace it with the head of Confucius. The result, as aesthetically ludicrous as it was spiritually tragic, had all the dignity of a Funko Pop figurine. Bitter Winter, an online magazine that covers religious persecution in China, heavily publicized the “bizarre-looking ‘sinicization’ folly.” As a consequence, though the “village committee was very reluctant to dismantle the ‘Confucius statue,’ which was built at the cost of 2.4 million RMB (about $360,000),” after two weeks of tragicomedy the hybrid statue was fully dismantled. Gone now is the First Guanyin of Shandong, never again to grace the Holy Water Pond Folk Culture Park in Pingdu City. Pulled down around the same time was the Chairman Mao Buddha Temple in Ruzhou City, a converted structure that similarly came in for shaming at the hands of Bitter Winter for its absolutely preposterous depiction of Mao in the guise of a Buddha, alongside such stirring inscriptions as “Lord Mao is the new Jade Emperor, who controls the heavens, the earth, and the human world,” and “Taoism and Buddhism will be attributed to the teachings of Mao Zedong.” At least the CCP is occasionally capable of embarrassment.

President Xi Jinping, in his infamous 2013 defense of the legacy of Chairman Mao, insisted that “because leaders made mistakes,

one cannot use these mistakes to completely negate their legacies, wipe out historical successes, and descend into the quagmire of historical nihilism.” Yet I can think of no better example of historical nihilism than the “sinicization folly” that descended upon cities of Pingdu and Ruzhou last year, nor any better confirmation of Marx’s adage concerning history’s tendency to repeat itself, first in a tragic mode, then as a crude farce.

IV

The Maronite monk Saint Charbel Makhlouf tells us that “the ignorant man clings to the dust until he becomes dust; the wise and prudent man clings to heaven until he reaches heaven. The place where you hang on, you will belong to it.” So too did he observe that “people have become arrogant, living amidst asphalt and cement; their minds have become asphalt and their hearts cement.” Starting with Mao, the authorities in mainland China have gone beyond even this, not content to cling to the dust in the fashion of all those besotted with scientific atheism, but seeking at every turn to pulverize into dust the thousands of years’ worth of heritage around them, replacing so much of their diverse, glorious bequest with lackluster asphalt, cement, gimcrack kitsch, and misery.

We in the West can certainly recognize these dynamics at work. Attorney General William Barr, in his October 11, 2019, speech at the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame, described “the force, fervor and comprehensiveness of the assault on religion we are experiencing today,” one in which “secularists, and their allies among the ‘progressives,’ have marshaled all the force of mass communications, popular culture, the entertainment industry and academia in an unremitting assault on religion and traditional values.” Barr declared, “This is not decay; it is organized destruction.” Thus far the canaries in this particular sociopolitical coal mine have been institutions, individuals, and sites like the Little Sisters of the Poor, Jack Phillips (of Masterpiece Cakeshop), and the Bladensburg Peace Cross. But wider measures, including those directed against foster parents and nonprofits that fail to toe the secularist line, are inevitable. In Great Britain, we already see tribunals ruling that biblical views are “incompatible with human dignity and conflict with the fundamental rights of others,” while in France the mere presence of posters stating that “la société progressera à condition de respecter la vie [society will progress only if life is respected]” was enough to bring down wrathful injunctions from the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo. All of this lends considerable credence to Barr’s recent rhetoric regarding the “organized, militant secular effort to drive religion out of our lives” and “out of the marketplace of ideas.”

Such occidental examples are comparatively tentative in relation to the assaults perpetrated during the Cultural Revolution and the ongoing efforts at “sinicization,” but they differ in degree and not in kind. In China we see the apotheosis — and not infrequently the reductio ad absurdum — of militant secularism, which demands that faith be sterilized, mutilated, and rendered entirely subordinate to Chinese scientific socialism, lest it pose offer too credible an alternative to the bleak vision of the totalistic state. The “religion of society,” as Roberto Calasso has termed it, has adopted an integralism of its own, and it jealously guards its newly fabricated rites and idols.

Bill Wilson Studio

The story that began with the eradication of the Zunghars and the Jinchuan, and continued through the orgy of destruction that Mao’s “great leap forward in religious affairs” through to the warmed-over revolutionism and nihilistic iconoclasm of the present-day CCP, would seem to leave little cause for hope. But just as we can be sure that “there is a day to come,” as Henry Edward Cardinal Manning maintained, “which will reverse the confident judgments of men,” so too can we can take heart in Hu Shih’s confident assertion that there is no level of violence that can wholly eradicate the conservative nature of Chinese culture. What is more, we ought to bear in mind the words of one of China’s most sensitive outside observers, the French ethnographer and poet Victor Segalen, who in his collection of prose poems, Peintures (1916), argued that

The others, those ruinous ones, those destructive ones, the Ultimates of each dynastic fall, those wicked Sons of Heaven who go, “belts loosened, by revolting paths” … you will agree that they are no less worthy to be seen, since they are no less necessary! The First Ones are lauded, called Founders, Renovators, Law-Givers, Mandatees of the high and pure Lord-Heaven…. But how then can one renovate, how to restore order without first of all installing disorder? How can justice be admired and stimulate fine deeds for its sake, unless from time to time Injustice reigns dancing on the world? How can the Mandate be obtained, unless contrary precursors, devoted beyond death, even as far as posthumous contempt, prepare the obverse of the task.

We who live in what Buddhists call this mofa, this “Degenerate Age,” in what Dietrich von Hildebrand rightly called “this age of relativism and dehumanization and depersonalization,” can take a great deal of solace in this line of thinking.

But if comfort is what we are looking for, one of the best places to look for it may be back at 1 West Mount Vernon Place in Baltimore, where the bodhisattva Guanyin remains atop her humble plinth. As the Perceiver of the World’s Lamentations, she has, in the Buddhist tradition, been subjected to all the enormities and indignities of which mankind is so eminently capable. Her effigies, as we have seen, have paid quite the price for this, in Kulja, in the Daluo Mountains, in Beijing, in Guangdong, in Shandong, in far too many other places to mention. But there remains, for all that, a wry smile on her face — not quite a smirk, but an expression of the utmost confidence in the seaworthiness of the Barque of Salvation amidst the countless tempests of our degenerate, dehumanized age. In the visage of Guanyin we can find confirmation that injustice will not reign dancing on the world in perpetuity, and that the song of the future will not be one of unremitting sorrow. What a fitting monument this sculpture is to the potential of Chinese and indeed to human civilization. There is absolutely no comparison between it and the buffoonish Guanyin–Confucius pantomime mashup that disgraced the Holy Water Pond Folk Culture Park in Pingdu City for those two embarrassing weeks last year. We ought to ask ourselves: How much richer does the former make us? How much poorer the latter? And how long must we continue to stumble down the “revolting path” that descends from one down to the other?