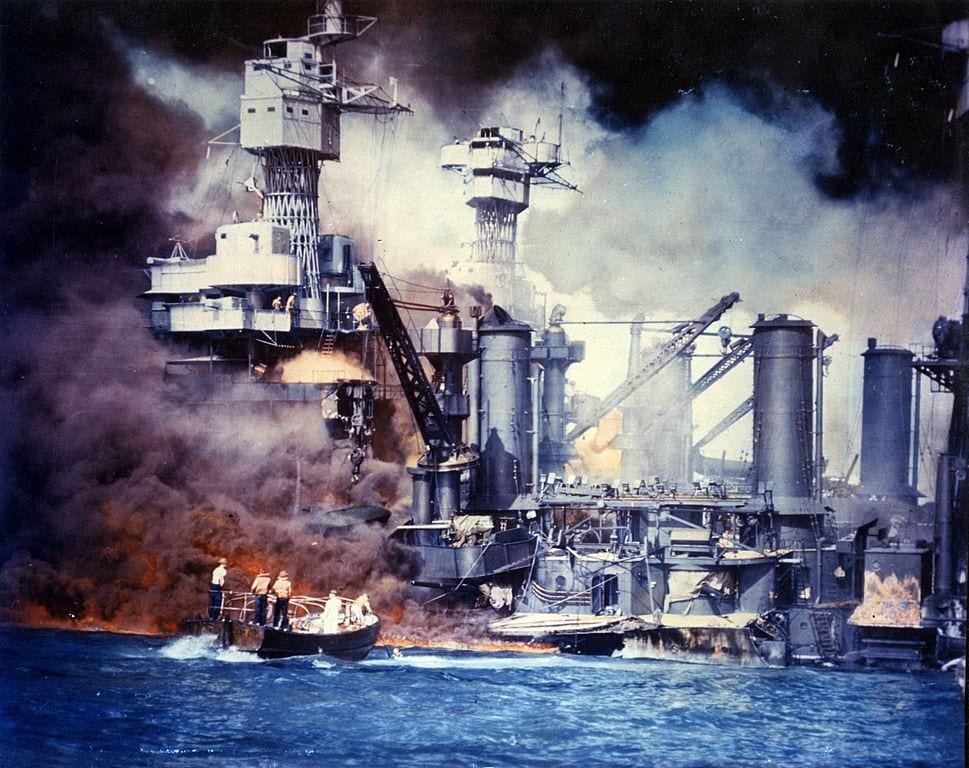

The first bomb fell a little before morning colors and by the time the attack was over, less than three hours later, the U.S. Navy had lost almost all of what it considered its capital ships. These were the battleships, one of which had blown up when a Japanese bomb penetrated a magazine where powder for the ship’s main batteries was stored. What is left of the U.S. Arizona still lies on the bottom, in the mud of Pearl Harbor. There is a monument built over the ship’s ruined hull, with the names of her dead — 1,117 of them — inscribed on one wall. You can look down into the water and see the spectral outline of the ship’s hull. It is a tomb, of sorts, holding the remains of 1,102 of those Arizona dead. Small red and blue ribbons, made by oil still leaking from the ship’s bunkers, drift in the water over the ship’s carcass.

All of the eight battleships that were in port on that Sunday morning were hit. The Oklahoma took nine torpedoes and rolled over, trapping many of its crewmen below decks where they began banging on bulkheads to get the attention of potential rescuers. The sound of that tapping haunted the men trying to get to those survivors and eventually 32 were rescued. Many more were not. Of the 2,335 who were killed in the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor, 429 were from the Oklahoma.

Aboard West Virginia, three crewmen were similarly trapped. They found an air pocket where they huddled and waited for rescue. It did not come. It was not possible to get to the men who continued their tapping. They had a calendar and they crossed off each day once they had survived it. When their bodies were found, long after the attack, that calendar showed they had lasted sixteen days before they ran out of air.

The Oklahoma was so badly damaged that it could not be repaired and returned to service. The other battleships, to include West Virginia,were repaired and sent back to war. West Virginia took part in the last battleship action in history when the U.S. “crossed the T” of a pitifully meager Japanese force in the battle of Surigao Strait.

The Japanese believed that they had won a splendid and complete victory at Pearl Harbor. They had achieved utter surprise and they had broken the backbone of the United States Navy which, without battleships, could not challenge the Japanese for control of the Pacific.

So, its leaders believed, that for many months, even years, Japan could consolidate the empire it had seized — or soon would, as in the case of the Philippines — and be secure against any challenge by sea.

However, in war, it sometimes seems there is nothing so uncertain as certainty.

The Japanese had won a splendid victory but…

Among other things, they had gone after the wrong objective. They wrecked the battleships at Pearl Harbor by launching attacks from six aircraft carriers. The U.S. Navy had only three carriers in the Pacific on December 7, 1941. None of them were at Pearl Harbor.

A little over four months later, the U.S. was launching an airstrike on the Japanese islands. From an aircraft carrier. Less than two months after that, at the battle of Midway, planes from three U.S. carriers sank four of the six Japanese carriers that had participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was the beginning of the end of the Japanese navy and, indeed, the Japanese nation. And it was certainly the end of the battleships which had become, in one morning, almost irrelevant.

The Japanese not only missed the U.S. carriers at Pearl Harbor, after two successful strikes on American ships and planes, they also passed up on a third that would have targeted fuel storage and repair facilities. These were not high profile targets. But the loss of them might have made Pearl Harbor useless as a base and U.S. operations in the Pacific would, of necessity, have then been launched from California and Washington. Japan would have bought more room and more time in which to fortify an island ring of defense.

And, most likely, still have lost the war.

At one point in the months after Pearl Harbor and Midway, the U.S. Navy was down to one operational carrier in the Pacific. At the end of the war, less than four years later, it had over one hundred. We could build them faster than they would ever be able to sink them. The losses at Pearl Harbor were inconsequential.

Still, all these years later, on December 7th, one thinks about that day and that attack. People have been studying Pearl Harbor and learning its lessons for almost eight decades.

Pearl Harbor is synonymous with surprise in war and, perhaps, the most successful — not to say audacious — surprise attack since that Greek stunt with the wooden horse. An example of overwhelming defeat, however temporary, as a result of surprise. Something to which America seems especially vulnerable.

The U.S. was surprised in Korea, first when North Koreans attacked, and then when the Chinese came in.

Surprised in the Cold War when the Berlin Wall went up

Surprised in Vietnam by the Tet Offensive.

Surprised when Iraq invaded Kuwait.

Surprised by the attacks of 9/11.

The attack of December 7th, however, is the sovereign surprise attack, catching the U.S. unprepared and even unbelieving. Which is summed up by the words that went out over the radio, once the bombs and torpedoes were exploding.

“Air raid, Pearl Harbor.”

And then.

“This is no drill.”

Complete surprise is when you can’t really believe it is happening.

And at Pearl Harbor, at first, they couldn’t.

It remains a day to remember.