I first met Ronald Reagan in the early 1970s. It was not, as someone might have said in one of his B-movies, an auspicious beginning. At the time I was the editor of King Features, the Hearst-owned syndicate that then billed itself immodestly but not inaccurately as the “world’s largest newspaper syndicate.” The reigning monarch of King Features when I arrived was Walter Winchell, he of the police radio, the ubiquitous tipsters, and the three-dot prose style. Walter had been a dominant figure in both print and electronic media for 30 years. Mr. and Mrs. America, as he called his audience, couldn’t seem to get enough of his brassy, apparently inside dope. But as it happens to all writers sooner or later, he had begun to repeat himself and, even more problematic for his boy editor (me), he had begun to make stuff up. Bad stuff. About people who could afford to hire lawyers. Toward the end of his career, and the beginning of mine, Walter had become a litigation-magnet and it became my unhappy duty to retire him after one of the most spectacular careers in the history of American journalism.

Thus was born the career of Robin Adams Sloan, a saucier-than-thou gossip columnist who not only succeeded Winchell but quickly became the rage of the syndication business, appearing in hundreds of newspapers around the country. Unlike Winchell, however, Sloan was a dream to work with — no creative differences, no deadline crises, no hassle. Sloan quickly became my model employee because, I now confess, Sloan did not exist. Like a general fighting the previous war, I had resolved to syndicate the un-Winchell, and in Sloan I found an androgynous byline behind which lurked no personality quirks whatsoever. Most of the actual writing for the Sloan column was done by three well-placed sources in the media world to whom I gave assurances of anonymity. Not a good idea. These well-informed sources were thus invited to let fly with their private furies, and it would be left to me to stand behind their copy. Only later did it occur to me that this arrangement amounted to a kind of moral hazard, a journalistic version of the S&L crisis of the 1980s. That is to say, whenever A’s risk is underwritten solely by B’s credit, A is likely to slip the bonds of discipline.

Well, Robin Adams Sloan slipped the bonds of discipline early and often. We went after celebrities with gusto, giving it to them, as a former president used to say, with the bark off. And then perhaps inevitably, with the cheers of the crowd echoing in our ears, we went too far. One day we released an item reporting that one of Hollywood’s best-known figures had ordered up a pubic merkin. Why, you may ask, would responsible journalists distribute such an item? What were we thinking? Good questions, those.

For some reason, no doubt providential, there followed nothing but silence. (A colleague pointed out helpfully that abridged dictionaries sometimes omit the word merkin.) We had learned a lesson nonetheless. Robin Adams Sloan settled quickly (and for those of us who had reveled in the rock-’em, sock-’em days, a bit sadly) into journalistic responsibility. But even as we locked the barn door we learned that at least one horse had escaped.

The Sloan column had also reported that Ronald Reagan, then recently re-elected as Governor of California, had taken to dying his famously chestnut-brown hair. I noted the item when it came across my desk, called Robin (I thought of my three sources as, respectively, Robin, Adams, and Sloan), and asked where she got the item. She assured me that it had come directly from Reagan’s barber. That Was good enough for me. It seemed scarcely man-bites-dog news that a middle-aged man with a background in Hollywood and a foreground in politics would color his hair. No big deal. Soon after the story was published around the country, however, the Governor’s wife, Nancy, passed word to us that the story was untrue and that she would appreciate it if we corrected the record as soon as possible. I checked again with our source’s source, the barber in question, and he reaffirmed his account. He said he even had clippings to prove the point. Thus reassured, I brushed aside Mrs. Reagan’s objections with what I hoped was a polite but professional and case-closing note.

What I then encountered, however, was not Nancy with the laughing eyes but rather Nancy with the sharpened claws. Nancy Reagan happened to be married to the governor of a state in which the Hearst Corporation owned major media, real estate, and other politically sensitive properties. On one occasion, she deftly brought it to my attention that the Reagans counted among their personal friends the publishers of Hearst newspapers in Los Angeles and San Francisco, both of whom, as luck would have it, were named Hearst. I began to see my corporate career flashing before my eyes. I was not at all sure that the Hearsts’ enthusiasm for fearless newspapering extended to coverage of their highly placed political friends.

—

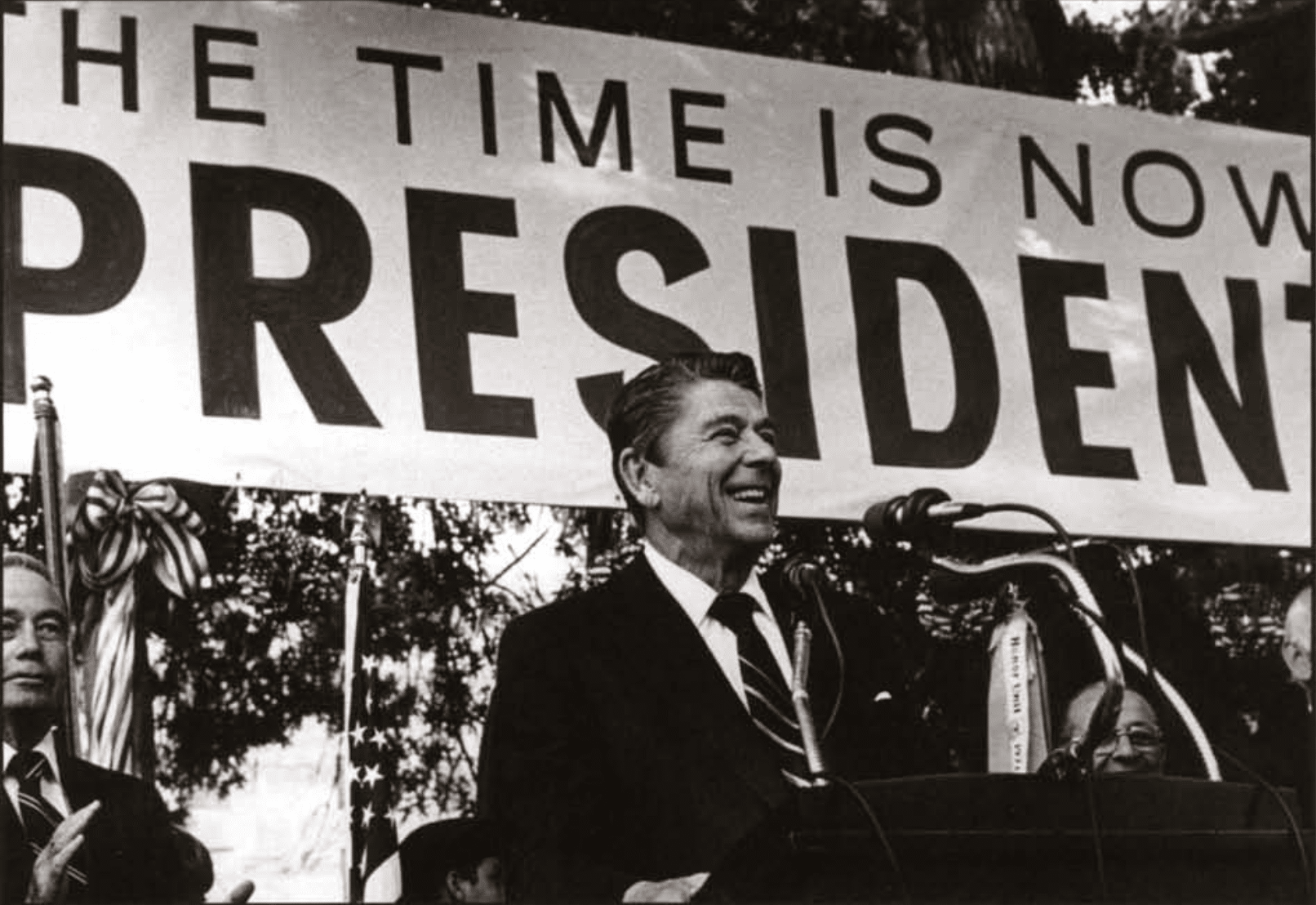

It was against this background that I received, out of the blue, an invitation to lunch with Ronald Reagan. William A. Rusher, the legendary publisher of National Review, called to suggest that it might be good for me to meet the rising political star and, in a bit of forced symmetry, that it might be good for him to get to know me. I jumped at the chance. The arrangements were set for a quiet, elegant restaurant on Manhattan’s East Side, and I arrived promptly at the appointed hour.

Just as Rusher and I sat down in the private room off the main dining area, Reagan strode in. I didn’t actually see him — my back was to the door — but I felt him. As I was to be reminded many times over the following years, Ronald Reagan brought with him to every encounter a charged field of personal charisma. Amid a cloud of bonhomie dotted with rosebud cheeks, with the hankie squared and his suit just back from the cleaners, you would have no trouble casting him as … the rising political star. He greeted us as soon-to-be old friends and introduced us to his two bodyguards, who then stationed themselves at the door to block unexpected visitors. The sight of these two large, crewcut men with plugs in their ears, motionless except for darting eyes that followed every clam persille to every pair of thin lips, would have chilled most dining rooms. Not this one. It was an international hotspot just a few blocks from the United Nations and favored by ambassadors and their security details. Probably a third of the men in the room were carrying (barely) concealed weapons. That’s not a sexist remark, by the way. In those days, most of the ladies who went to lunch did so unarmed.

We took our seats with Reagan in the middle, I to his right. And the investigation commenced. Every time that Reagan turned to speak to Bill Rusher, I would lean in and squint at the hairs on Reagan’s neck. Conditions were good. The lighting was lunch-bright and not dinner-intimate. And Reagan had one of those 1950s haircuts buzzed up the back and over his ears. By the third squint, I was convinced. Dammit. There was but a single gray hair peeking from his neck, just the touch to lend verisimilitude to Nancy’s claim. Whatever his other vanities might be, Reagan was not dying his hair. (“Thank you, waiter, I’ll have the braised crow in a light mustard sauce.”)

With that piece of business completed, I then joined the conversation in progress and was soon warmed by the toasty Reagan charm. First, the jokes.

The wide world has heard many of them, some more than a few times. The private versions tended to be a little more politically incorrect and thus involved more horny girls, bibulous priests, and other unmentionables. Over the years people from every corner of the human condition had found the experience thoroughly enjoyable — partly because the jokes were oldies but goodies, partly because Reagan’s rendition of them was so polished, and most of all because few people could resist the very idea that Ronald Reagan was taking the trouble to entertain them.

—

After the jokes and the appetizers, we got down to more substantive talk of goals and tactics. Conversations with politicians, of course, tend to be heavily autobiographical and in this respect Reagan proved to be no exception. From both his comments and his questions it was clear to me that he wanted to be President and that he was prepared to take risks to achieve that objective. But his ambition for the office seemed neither palpable nor ravenous. In a way it was not even personal. He was in politics, it seemed to me on first meeting, for the right reason: he saw his political career as an efficient vehicle for advancing important ideas.

Much to my surprise, the longer he talked the more plausible his White House ambitions began to sound. Surprise, indeed. Remember, I was living and working close to the heart of the Eastern media world where it had long been established wisdom that Reagan was a lightweight cowboy actor who would never be a serious national figure. I like to think that I began to form my own opinion of Ronald Reagan that day.

—

First I had to fix things with the missus. In a series of calls, letters, and public grovelings that will one day win me a footnote in the history of sycophancy, we finally secured Mrs. Reagan’s forgiveness. Toward me, she was in the end thoroughly gracious, as if we had worked together toward a mutual goal. We never became friends — this was a much larger episode in my life than hers — but we established a working relationship that carried on into her White House days when, by that time a television producer, I helped produce spots for her anti-drug and Foster Grandparents programs.

As for the Governor, he and I began a long distance, very one-sided political courtship. I would look for opportunities to build up our tenuous relationship, sending him clips and speech ideas from time to time, pointing out a media opening here, a fundraising salient there. He or his associates would respond just often enough to keep the channels open. By the time he was sworn in as President in 1981, there remained for me only one more question to be answered about Ronald Reagan. Would I help his “revolution” by working inside the administration, or by continuing my work in the private sector?

As so often happens in political life, the answer that finally emerged was, “all of the above.” After a series of stop-start talks with White House aides, I became both an independent contractor and a political appointee. First, I was hired to produce the President’s video messages — everything from his New Year’s greeting to the Soviet people to his salute to the newly elected president of Peru to his toast to Mr. and Mrs. Lew Wasserman on the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary.

This type of “video message” is now a standard item in the communications tool box. At the time, however, it was new and different and born of necessity. Pressed for time in the presidential schedule — and always eager to avoid the marginal plane ride — Reagan began to travel to ceremonial events “by television.” What was seen at first as a poor substitute for the President’s personal appearance became in time what political observers regarded as still another brilliant innovation by the Great Communicator.

You have probably consumed a few of these messages yourself. At a ballroom dinner — and not infrequently at simultaneous ballroom dinners at the far ends of this large country — the lights dim, a baritone voice intones, “Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States … ” and there, on a 50-by-30-foot screen, appears the reassuringly familiar face of the Leader of the Free World. In the early days, we would send or satellite these tapes with quasi-apologies, stressing that only history-sized events had prevented the President from joining the fun that night in Omaha, or wherever. As the program rolled out, however, it was soon demonstrated that the impression he made by videotape was far more powerful than if he had walked on stage, appearing ant-size to those in the back row, and stumbled through a few weary remarks at the end of a long dinner tacked on to the end of a long flight. It turned out to be a win-win-win. The President got his sleep. The diners got a star turn. And the host organization got a professional videotape for promotional use.

—

By 1983, I had become a member of the administration, pleased to be offered a Presidential appointment to the Board of Directors of the Communications Satellite Corporation — or Comsat — which was the principal U.S. provider of global communications to many voice, video, and data customers. The appointment was satisfying at several levels. It engaged my career-long interest in communications technology; it afforded me the opportunity to represent the President in international affairs; and, inasmuch as it was a part-time assignment, it permitted me to pursue my private business interests. I accepted with genuine pleasure.

How did I get the job? Any presidential appointee who tells you he knows the real answer to that question is either underinformed or less than candid. I like to think that the President wrapped up the discussion by saying, “Neal Freeman is one of the truly outstanding communications executives in the world today. Our policy initiatives, the administration, and indeed the future of the global economy will benefit greatly from his service in this key post.” But then again, he might have said, “Hey, it’s not the Pentagon. How much damage could he really do?”