When tears flow, they wipe them with a handkerchief,

When blood flows, they hurry with their sponges,

But when the spirit seeps out under oppression,

They don’t come running with an open hand,

’Til God, with a flash of lightning, sweeps them himself —

Only then!

— Cyprian Norwid, “Mercy” (1866)

There is no better clock than the sun, no better calendar than the stars in the night sky. Until quite recently in human history, it was the natural structure of the day, as opposed to quantitative clock time, that determined life’s rhythm. Timekeeping was itself a purely local matter, with noon arriving when the sun attained its zenith overhead. Church bells would toll at daybreak, midday, and eventide, rather than at the artificial constructs of 6 a.m., noon, and 6 p.m., just as minarets in the Muslim world would issue their Salah calls to prayer at Fajr, Dhuhr, Asr, Maghrib, and Isha. The Han-era Chinese, for their part, evocatively divided their days into dawn, morning light, daybreak, early meal, feast meal, before noon, noon, short shadow, evening, long shadow, high setting, lower setting, sunset, twilight, and rest time. Attempts to introduce secular time were initially resisted, as in 1866, when the mayor of the French town of Autrécourt-sur-Aire mandated that the midday bell ring at precisely 11 a.m., so as “to alert all those who are in the fields and need to go home and fetch something for the harvesters to eat,” only to be be informed by the curé of Saint Avitus that “the bells were not solemnly blessed in order to call all the world to soup.” Psalm 55 had set a firm precedent, after all, and with no mention of specific Universal Time Coordinated hours:

As for me, I will call upon God; and the Lord shall save me.

Evening, and morning, and at noon, will I pray, and cry aloud:

and he shall hear my voice.

This timeworn, flexible, hyperlocal way of life was hardly conducive to the burgeoning telegraph, railroad, and global financial industries, and in 1884 the attendees of the Prime Meridian Conference divided the globe up into the 24 time zones we know today. Secular time was firmly in the ascendant.

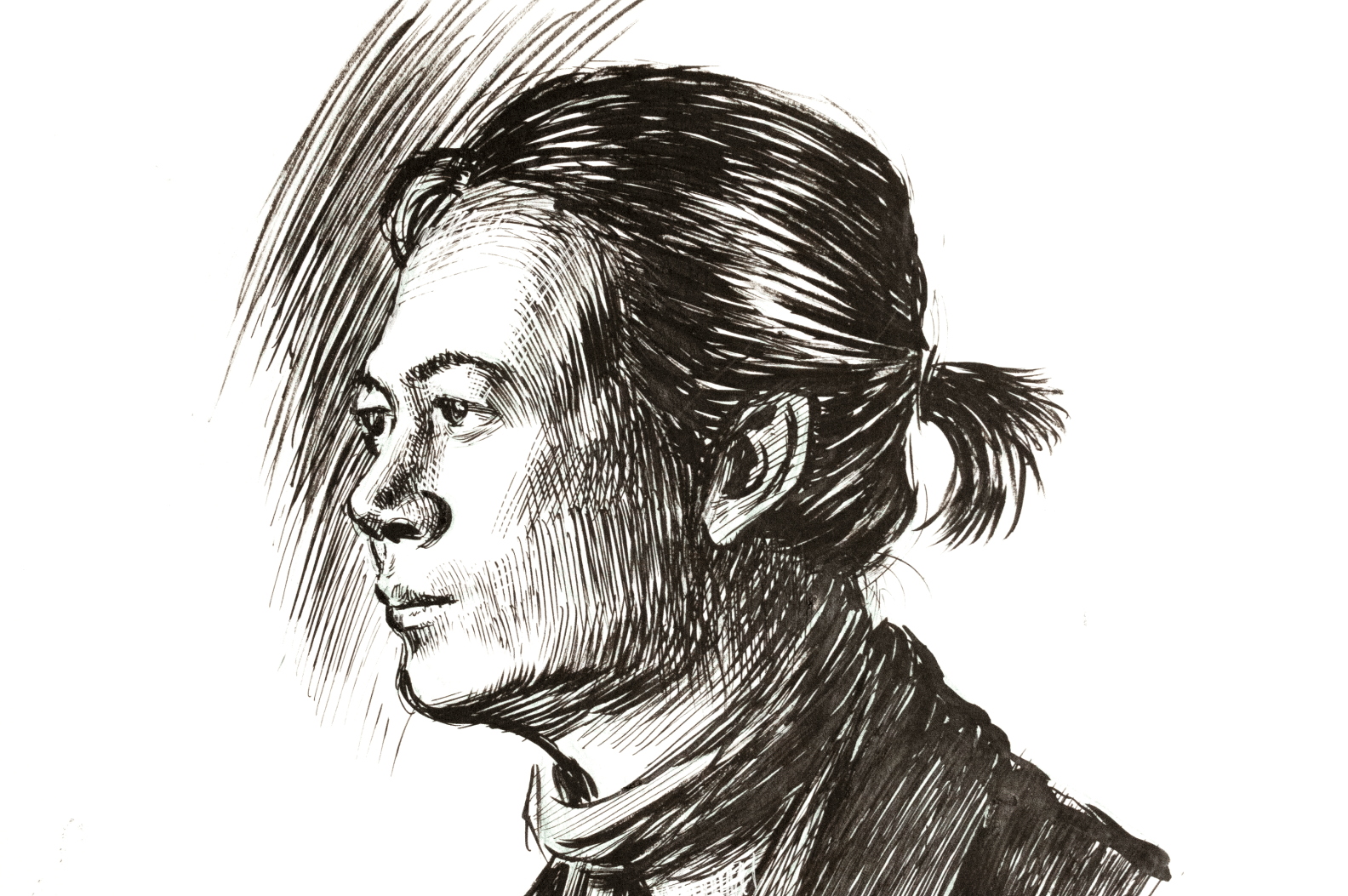

Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, in his satirical 1954 novel The Time Regulation Institute, described how the Turkish adoption of Western time through the Gregorian Calendar Act of 1926 constituted a sort of fall from Eden’s divine grace. The freedom afforded by the old ways was like “a lump of gold concealed in my innermost depths, a bird trilling in a tree, sunlight playing on water,” but it precipitously gave way to the rigid strictures of bureaucratic modernity. “My life’s rhythms were disrupted, it would seem, by the watch my uncle gave me on the occasion of my circumcision.” The very notion of human progress, Tanpınar suggested, “begins with the evolution of the timepiece. Civilization took its greatest leap forward when men began walking about with watches in their pockets, keeping time that was independent from the sun. This was a rupture with nature itself. Men began following their own particular interpretation of time.” Earthly existence went from being cyclical to being linear, with profound consequences in every walk of life. As the Korean-born, Berlin-based cultural critic Byung-Chul Han put it in his 2009 treatise Duft der Zeit, or The Scent of Time, “mythical time is restful, like a picture,” while “historical time, by contrast, has the form of a line which runs or rushes towards a goal. If this line loses its narrative or teleological tension, it disintegrates into points which whizz around without any sense of direction,” and between these points “necessarily yawns an emptiness.”

Han is not the first German philosopher to make this trenchant observation about modern life. Georg Simmel, in The Philosophy of Money (1900), warned fairly early on of an “extreme acceleration in the pace of life, a feverish commotion and compression of its fluctuations,” leading to the “temporal dissolution of everything substantial, absolute and eternal into the flow of things, into historical mutability, into merely psychological reality,” while Martin Heidegger similarly cautioned against the “planet-wide movement of modern technicity,” which inevitably “dislodges man and uproots him from the earth.” In a similar vein, the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, author of Homo Ludens and The Autumn of the Middle Ages, described in the opening lines of his 1935 polemic In the Shadow of Tomorrow our “demented world” hurtling forward in a “state of distracted stupor, with engines still turning and flags waving in the breeze, but with the spirit gone.” In spite of these warnings, the inhuman scale and unnatural tempo of modern life only accelerated in the decades that followed.

The natural rhythm of daily life and ritual once protected us from the emptiness, feverishness, insubstantiality, and stupor described by Simmel, Heidegger, Huizinga, and now Han. There was something ennobling about a society capable of repose, stillness, and deliberation. For Friedrich Nietzsche, in a “noble culture” people are confident, and do not “react immediately to a stimulus,” capable as they are of letting “foreign things, new things of every type, come towards you while assuming an initial air of calm hostility.” An “inability not to react” is nothing more than “a pathology, a decline, a symptom of exhaustion” brought about by the hyperkinetic pace of modernity with its constant informational overload. This estrangement from the natural order has taken a terrific toll, and it is easy to place the blame on the industrial revolution, which added so much to the world — overcrowded cities, towering trash heaps, environmental xenoestrogens, nutritionally deficient monocultural cash crops, a repulsive built environment, and disposable consumer goods — while draining it of its biodiversity and cultural diversity, its age-old traditions of bespoke craftsmanship, and above all its collective spirit. These are all things that can conceivably be mitigated to a greater or lesser extent, but Byung-Chul Han, in his newest essay collection, Undinge, or Non-things, has sounded the alarm about the next and even more sinister stage of societal evolution, wherein the terrestrial order itself gives way to the rising digital order.

“Today’s world,” Han warns, “is fading away and becoming information,” as “everything is seized by disappearance, by a progressive dissolution.” People have reverted to the state of hunter-gatherers, Phono sapiens as he calls them, in tireless pursuit not of nutriments but rather digital information, increasingly “blind to still, inconspicuous things, to what is common, the incidental and the customary — the things that do not attract us but ground us in being.” This is the ultimate rupture with nature itself, not just a perversion of it but an outright nullification. It is no secret that we increasingly inhabit a world of “non-things” — social media profiles, cloud storage, digital photos, e-books, grotesque Goblin Town and Mutant Ape Yacht Cub NFTs, etc. — but no one has done a better job illustrating the troubling consequences of this transition than Han, a philosopher who remains attuned to what he calls the “magic of things.”

There are certain personal possessions, even some mass-produced items, that retain some modicum of magic even in this soulless, artless era. An analogue watch, Han writes, “provides us with information regarding time, but it is not an information; it is a thing, even an adornment. Its material aspect is central to it.” Han describes his fondness for an old silver Junghans watch, and I am again reminded of a passage from Tanpınar’s The Time Regulation Institute, concerning how “a watch can become a man’s dearest friend, ticking with the pulse in his wrist, and growing heated with the same fervor, until they are as one.” And I think of my own mechanical watch, a Prim manual-wound timepiece manufactured in the Czech town of Nové Město nad Metují back in the ’60s, improbably surviving to the present day, its balance wheel, hairspring, lever, and escape wheel all lending it a certain soulfulness that an Apple Watch can never achieve, even if it is unable to register my blood oxygen levels or accidentally call people on my contact list.

The transition from analog and terrestrial to digital and cloud-based will always involve a loss of spirit, romanticism, and quality. One cannot, Han posits, “have, for instance, a personal copy [Handexemplar] of an e-book. A personal copy of a book is given its unmistakable face, its physiognomy, by the hand of the owner. E-books are faceless and without history.” Surely there is little comparison between, say, the signed first edition of Maurice Barrès’ Colette Baudoche that represents one of my most prized possessions and a Project Gutenberg plain text UTF-8 file of the same work. So too is there little comparison between, to take yet another personal example, the wonderfully expressive nib of my cherished Onoto de la Rue fountain pen, always close to hand, and something like the sterile, bluetooth-connected, lithium-ion battery-powered Apple Pencil. For all that, as Han sadly concludes, “the time of things close to one’s heart has passed,” for “the heart belongs to the terrestrial order,” and information capitalism has no need for the “magic of beautiful forms” and what they represent.

It was under the influence of Shintoism, and the belief that the sacred element of kami is to be found everywhere and in all things, that it became customary in Japan, as Han notes, for “people to bid farewell to things that they had used for a long time, such as spectacles or quills, by performing a ceremony in the temple.” In pre-communist China, the written word was held in such high esteem that books and sheets of writing were taken to the local Hsi-Tzu-T’a, or Pagoda of Compassionating the Characters, for a proper burial, while Jewish synagogues traditionally maintained genizot to serve as repositories for worn-out Hebrew-language books, papers, and even personal letters and legal contracts. Now there is little respect for beautiful forms, and in Han’s well-chosen words, “there are probably very few things to which we would grant such an honorable farewell. Things come into the world almost stillborn. They are not used but used up. Things get a soul only through long use. Only things that are close to the heart are animated.” The spirit is seeping out of us under the oppression of hyper-modernity, and our world of plastic things and digital non-things is a paltry sort of consolation.

Byung-Chul Han’s school of thought could be summarized with his dictum that “information by itself does not illuminate the world. It can even have the opposite effect. From a certain point onwards, information does not inform — it deforms.” Johan Huizinga, in his aforementioned In the Shadow of Tomorrow, made a similar point about the effect of scientism on our daily lives:

The means of apperception themselves are beginning to fail us … The phenomena which physics embodies in exact formulae are so remote from our plane of life, the relationships established in mathematics lie so far beyond the sphere in which our thinking moves, that both sciences have long since felt themselves forced to recognize the insufficiency of our old and seemingly well-tested logical instrument … Science seems to have approached the very limits of our power of thought. It is a well-known fact that more than one physicist suffers this continuous working in a mental atmosphere for which the human organism does not seem to be adapted, as a heavy burden, oppressing him sometimes to the point of despair … The layman may indulge in a longing for the comfortably tangible reality of older days … but the science of yesterday has now become poetry and history.

This is in turn recalls the work of Masanobu Fukuoka, the Japanese natural farmer who explained, in his deeply affecting 1978 Shizen Noho Wara Ippon No Kakumei, translated as The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming, how simple the world used to be, when “you merely noticed in passing that you got wet by brushing against the drops of dew while meandering through the meadow. But from the time people undertook to explain this one drop of dew scientifically, they trapped themselves in the endless hell of the intellect.” As Fukuoka elaborated, “in nature, the world of relativity does not exist. The idea of relative phenomena is a structure given to experience by human intellect. Other animals live in a world of undivided reality. To the extent that one lives in the relative world of the intellect, one loses sight of time that is beyond time and of space that is beyond space,” condemning one to live in the hell of the intellect, the hell of unceasing, ultimately useless information.

The way out of this digital inferno, for Han, is to pursue a life of calm, silent contemplation and introspection as best one can, for “only those who linger in contemplative calmness appear to God’s redeeming gaze.” Although Han is in many ways a deeply pessimistic thinker, and is writing largely for an equally despondent audience open to his critique of modernity, there is something comforting about this viewpoint. Consider Han’s daguerreotype analogy:

Absolutely silent perception resembles a photograph taken with a very long exposure. Daguerre’s photograph Boulevard du Temple actually shows a very busy street in Paris, but because of its extremely long exposure, typical of daguerreotypes, all movement disappears. Only what stands still is visible. Boulevard du Temple exudes an almost rural calmness. Apart from the buildings and the trees, only one human figure is recognizable, a man who is standing still to have his shoes cleaned. Perception of the long-lasting and slow thus recognizes only still things. Everything that rushes is condemned to disappear. Boulevard du Temple can be interpreted as a world seen through divine eyes.

The buzzing information, the background noise, the clamor and squalor and aesthetic horror of our age, are all ephemeral by design, and this planned obsolescence is modernity’s ultimate failing. All this mass-produced dross, and all these intangible digital non-things, must eventually pass, leaving behind mere blurs barely perceptible against the perdurable backdrop of nature, beauty, art, and civilization — assuming that we are able to preserve what remains of those things for the sake of posterity. Only then might we return to the mythic time we once knew, “restful, like a picture,” and in tune with the immutable Laws of Nature and Nature’s God, a world so memorably described and defended in Byung-Chul Han’s most recent, and arguably finest, collection of essays.