A year ago the Left was convinced that President Donald Trump was going to plunge the world into nuclear war in Korea. Today it is upset because he hasn’t done so — or at least has yet to achieve what no other president managed to do, force the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to disgorge its nuclear weapons. Neoconservatives are mad that he is talking with instead of bombing the North’s Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un. And that the president has mooted the possibility of withdrawing U.S. troops from South Korea.

It doesn’t seem to matter what he does or doesn’t do. The usual foreign policy suspects will never be happy with him.

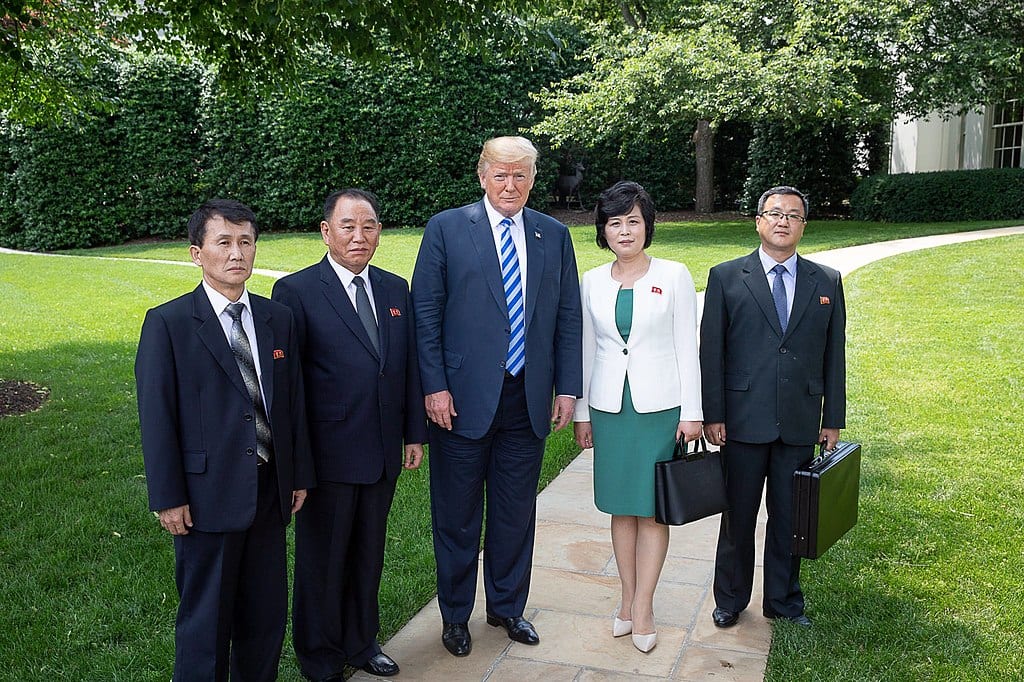

Not that such criticism bothers him. President Trump should combine two unpopular but excellent ideas: seek a deal with the North and withdraw American forces from the South. Indeed, a trade of troops for nukes would offer a near perfect resolution of the Korea challenge.

The Korean peninsula, for years a Japanese colony, became an American problem in 1945 after Tokyo’s surrender in World War II. Two Koreas emerged from the American and Russian occupation zones. In 1950 the DPRK’s Kim Il-Sung sought to forcibly reunite the peninsula. He nearly succeeded, before losing almost everything when the U.S. intervened to stop him. Then the People’s Republic of China joined the fight, leading to more years of bitter conflict and an armistice close to where the war started.

Since then the uniquely Korean cold war occasionally flared hot. For instance, a half century ago the North seized the American spy ship USS Pueblo, which is on display on the river next to the grandiose Victorious Fatherland War Museum. Less than a decade ago North Korean forces sank a South Korean warship and bombarded a South Korean island. With the two Koreas’ relatively short 160 miles long border the most heavily militarized real estate on earth, any renewed conflict would be destructive and bloody.

Although U.S. military involvement was necessary to preserve South Korean independence in 1950 and the immediate aftermath, the Republic of Korea took off economically in the 1960s and overthrew military rule in the late 1980s. Shortly thereafter the Soviet Union collapsed while China escaped its Maoist past. By then the South was capable of standing on its own militarily but, unsurprisingly, preferred to continue relying on U.S. military support. Today the ROK enjoys a 50-to-1 economic advantage and 2-to-1 population edge. America’s human tripwire is antiquated and should be ended.

Making the DPRK even more dangerous are its missile and nuclear programs. Presidents starting with George H.W. Bush have insisted that Pyongyang cannot be allowed to develop nukes, but it has done so. Neither engagement nor isolation deterred the North. But that is not surprising. Given America’s extraordinary military dominance, no small state, especially one so poor and essentially friendless, can survive Washington’s ill attention. In the case of Korea, long known as a shrimp among whales, survival also means balancing the regional powers, China, Japan, and Russia, all of which have sought to dominate the peninsula in the past. During the Cold War North Korea insisted on its independence from both of its communist neighbors, despite their support during the Korean War. A nuclear arsenal buttresses that independence.

Despite the North’s susceptibility to caricature — consider the depiction of Kim Jong-un’s father, Kim Jong-il, in Team America — its leaders appear to be ruthlessly rational. They have played a weak hand well, dominating international headlines despite being impoverished, alone, and reviled. Nothing suggests that they want their virgins in the afterlife rather than today. Kim Jong-un is not angling to exit this world on a radioactive funeral pyre. Which means deterrence will work. Despite the DPRK’s endless bluster and blather, Pyongyang is not going to intentionally start a war which it knows it would lose. Risks remain, since misjudgment and mistake always are possible, but America faced worse during the Cold War.

Indeed, Washington considered preventive war to stop both Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union and Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic of China from developing and deploying nuclear weapons. Mao appeared to be far nuttier than any of the Kims, suggesting that with its large population the PRC had no reason to fear a nuclear exchange. It turns out even that was bluster and blather. So the prospect of a nuclear North Korea should make Americans uncomfortable, not fearful.

Equally important, this danger arises only out of the defense commitment to the South. Pyongyang does not mindlessly and casually threaten to turn Beijing, Moscow, Hanoi, Delhi, Athens, Brussels, Paris, and Berlin into “lakes of fire.” That phrase typically has been used against the three nations seen as the DPRK’s enemies: ROK, Japan, and U.S. And America is on the list only because it has intervened militarily in Northeast Asia and arrayed itself against the DPRK. The latter knows that an unprovoked attack would result in devastating retaliation. But it hopes the threat of assault will dissuade Washington from striking. And, frankly, how could protecting the prosperous and populous South Koreans be worth risking the incineration of U.S. cities? The easy way to end that threat would be to turn South Korea’s defense over to South Korea.

What of the North’s apparent nuclear capability? Retaining a “nuclear umbrella” over the ROK would provide deterrence, assuming Washington’s promise was credible. But Pyongyang’s ability to hit the U.S. homeland would make any president hesitate to act. And this policy would keep America entangled in potential conflicts not its own. Controversial but perhaps more sensible would be to leave Seoul and Tokyo free to build their own retaliatory arsenals. The mere prospect of Japan possessing nuclear weapons likely would encourage the PRC to take a more active and positive role.

Nevertheless, it would be best for all concerned if the North did not develop nuclear weapons. But Kim will give up something so expensive to attain only if he receives something equally valuable in return. The promise of economic opportunity as well as immersion in diplomacy, a game which the 35-year-old dictator turns out to be quite good, are positive inducements. However, the president should offer another concession, one which he would like to take anyway: withdrawal of U.S. troops.

The possibility that Kim might demand that Washington take such a step has generated much commentary within The Blob. And the majority reaction has been horror, followed by the shrill demand that the administration respond no if the occasion arises. After spending years describing the dangers, horrors, and catastrophes that would result if the DPRK developed nuclear weapons, the foreign policy establishment found something even scarier: the specter of ending one obsolete foreign deployment. Better to forever face a nuclear-armed North Korea with a growing and more sophisticated arsenal capable of reaching America than to expect even one ally to take over responsibility for its own security.

This is a profoundly bizarre perspective. And one that suggests U.S. security, protection of the American homeland, is not a particularly important priority in Washington. Policymakers appear to be far more determined to subsidize wealthy foreign friends and allies and remake impoverished and failed societies abroad than to consider the interests of the Americans who do the paying and dying. The only official with genuine power who appears to think otherwise is President Trump.

He has made the Korea issue his own, rejecting conventional wisdom which failed to make America safer and more secure despite years of sometimes frenetic effort. With another summit in view, the president should offer a true deal of the century, trading troops for nukes. Real peace remains only a distant hope, but even that is better than no hope.

Doug Bandow is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. A former Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.