It has been a perilous few weeks for the Chinese Communist Party. The government faces wavering economic indicators compounded by the redoubling of its trade war with the United States, and mounting condemnation of the treatment of its Muslim Uighur population. To make matters worse for the Xi administration, protesters in Hong Kong have risen up in what could be one of the largest mass rallies in the region to date.

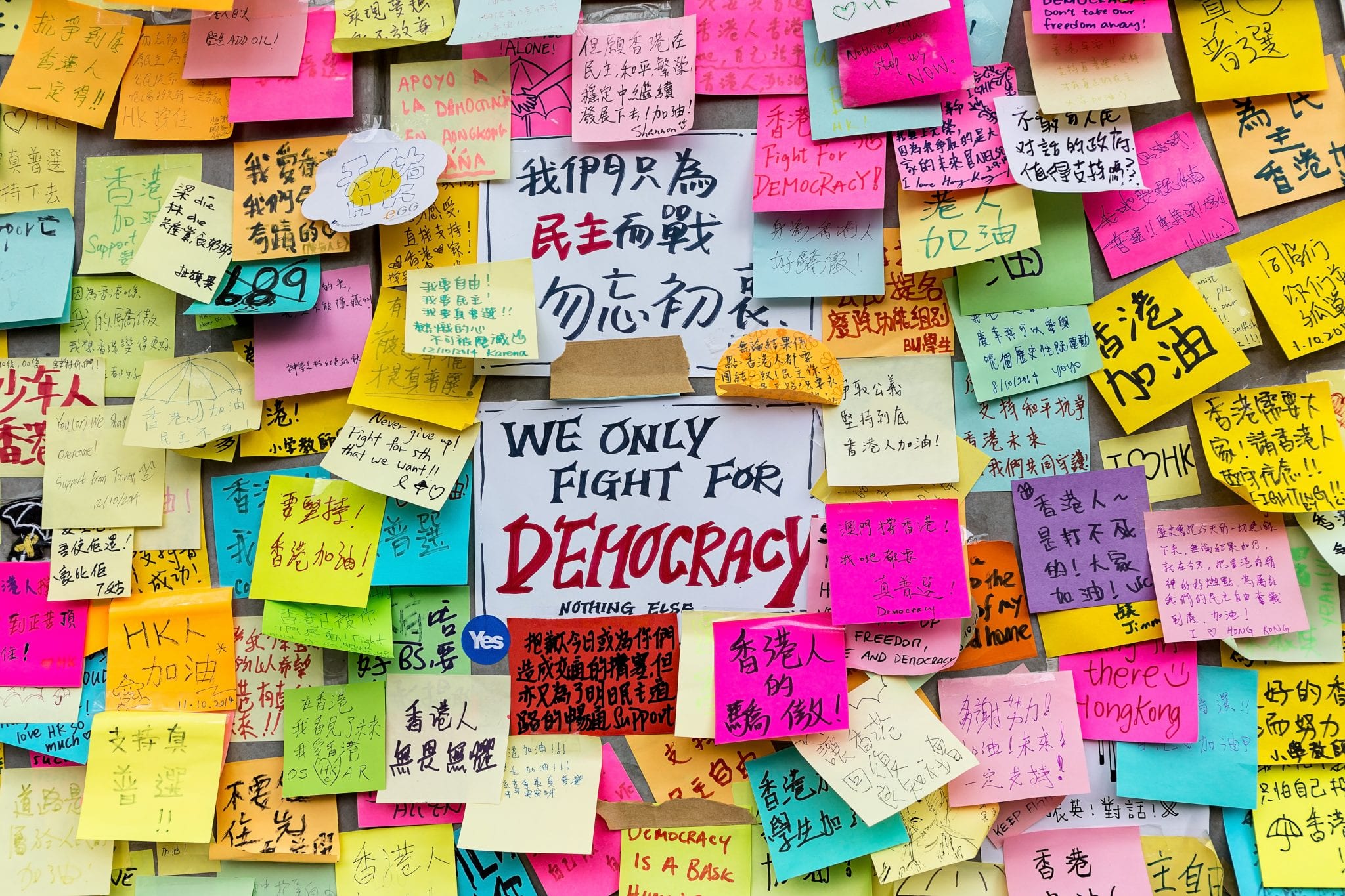

The demonstrations are being held over an extradition bill proposed by the Hong Kong government, which may potentially give Beijing a legal excuse to abduct political activists from Hong Kong to face prosecution in mainland China under pro-communist judges. The bill is the latest in a long line of attempts to undermine the political and judicial independence of the city, which is one of two regions of China that maintains any semblance of democracy.

CNN reported that the initial protest on June 9th drew as many as one million participants, more than the peak turnout during the Umbrella Movement protests that roiled Hong Kong in 2014. The protesters battled with riot police into the night, attempting several times to storm the legislative building. The debate that was scheduled for the bill was eventually delayed after entrances to the building were cut off, preventing legislators from entering. Another rally is planned for the weekend, promising continued unrest.

The odds have, as always, been stacked against pro-democracy and pro-autonomy forces in the region. The 2014 protests, despite their scale and duration, failed to spur the government toward any meaningful reform. It appears that Beijing intends to pursue a similar no-concessions policy this time, dismissing the protesters as marginal troublemakers and using a mix of censorship and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks to prevent information from spreading to the mainland. Carrie Lam, the CCP-backed Chief Executive of Hong Kong, has followed her handler’s line and refused to budge on extradition. It seems at first that the events of half a decade ago are likely to repeat themselves: huge protests that are ignored by the government and eventually die out, followed by clandestine crack-downs and arrests targeting the participants, sometimes years later.

In 2019, however, the calculus appears to be somewhat different. The Chinese government is facing an unfamiliar crisis that is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Plunging consumption and a tightening job market suggest that an economic slowdown, or even a recession, is approaching. Its position is further being weakened by the United States’ full-steam tariff policy, which President Trump is threatening to further escalate. An oft-repeated claim about China is that the Communist Party’s legitimacy lives and dies with its ability to provide sustained economic growth. The next few years will test whether this is the case.

As the gateway to China for foreign companies, Hong Kong will be central to any Chinese effort to avoid being economically isolated by America and her allies. Meanwhile, the city’s democratic institutions will continue to stand as a testament to what is possible for the rest of the country.