Pianist Adam Golka is celebrating Beethoven’s 250th birthday with a concert series called 32@32, in which the 32-year-old musician will play all 32 Beethoven sonatas. Saint Thomas Church in New York City is one of his hosts, and the first of eight segments premiered last weekend.

I know a lot about this because I hit poll/projection/prophecy/panic overload late Wednesday night and found myself digging through emails looking for videos of live-streamed concerts I’d missed while focused on election things.

This is a good way to cope with stressful situations, the ones that nothing can solve but time: find something more absorbing. Music, thank God, asks for your full attention, your emotions, whatever you can give it. When I was younger and in possession of a piano, I would practice or sight-read for hours to put myself in a place where I could focus on pure problems like trills and tricky time signatures. And, sure, pound out the negative feelings.

So Golka’s first concert was a grace. He played some “early gems” and the Waldstein, a magnificent, technical monster that only a pianist with real heart can tame.

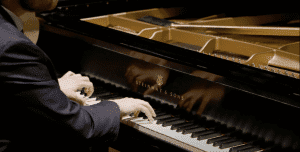

Adam Golka in 32@32 concert at Saint Thomas Church in New York City, Oct. 24, 2020 (YouTube screenshot)

His performance reminded me of something that we are missing during COVID times: seeing music, and the way musicians work. Golka is an expressive pianist — in his face, sure, but more importantly in his sharp technique: his hands, wrists, and elbows are riveting to watch because his every move is engineered toward bringing out the fullest possible sound.

Adam Golka in 32@32 concert at Saint Thomas Church in New York City, Oct. 24, 2020 (YouTube screenshot)

Music is often defined, simply, as sound moving through time. And somehow feeling fits in there, too.

Golka’s concerts helped in thinking through the relation between those things. Between sonatas, the concert series features interviews with teachers, other Beethoven experts, students, and more. As a pianist who first played all 32 sonatas at 18 (18!), Golka knows how to talk Beethoven. He’s a quietly winsome interviewer and an insightful listener, especially when offered suggestions on playing the sonatas.

One of the most wonderful things about watching excellent musicians is seeing how easily they take instructions — the lightbulb flashes on, and instantly understandings, even friendships, are formed between teacher and student, performer and composer.

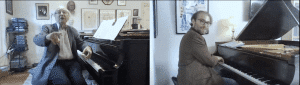

The latter relationship takes more time, it seems. Beethoven great Alfred Brendel, who has recorded three versions of the sonatas throughout this life, told Golka the slow movements changed the most over the years: “For the slow movements, one simply has to get older.” In the first version, they were like a blank map: the boundaries were there, but the terrain was empty. As he got older, he could see more, and fill them in.

Alfred Brendel and Adam Golka (YouTube screenshot)

So, over time, the sound of Beethoven develops one’s emotions and understanding of the music and the composer’s mind.

To understand the sonatas fully, though, Brendel said, you’d have to be about “110 years, at least.”

Regardless, someday, I’ll play Sonata No. 1 again, with a bit more experience and a lot more rust. But first I have to figure out if I can squeeze a baby grand piano into my modest living room.

More big news: Live orchestra music returned this week. Sort of.

Yesterday, the Boston Symphony Orchestra hosted its first rehearsal since March. As far as I know, Dallas Symphony Orchestra is the only other currently in action. The BSO will be launching a series of digital concerts Nov. 19, so none of us are invited — yet.

The orchestra has grown in its COVID absence. Or at least its stage has: the BSO will perform on an extension the size of an extra stage in order to keep that all-important six-foot distance.

It looks pretty wild, like the orchestra exploded:

The BSO in rehearsal, Oct. 28, 2020 (Aram Boghosian)

And the sound is spread out, too, at least from what I could tell in their preview video. The music seemed broader, wider, a surround-sound orchestra. Julianne Lee, assistant principal violinist of the BSO, said before a recital last month that the six-foot distance was initially disorienting. But “just as our eyes grow accustomed to the dark and eventually see more, our ears grow accustomed to the distance and we learn to hear more and listen better.” She said they all couldn’t wait to sit close to one another again, but when will that be?

So the BSO chose a fitting piece — and a total jam — for their return concert: Dvorak’s New World Symphony.

A new world after COVID shutdowns: no kidding.

If it’s hard to remember, don’t worry. I’m not asking to be condescending, but because, studying English in college, I’d guess I spent the majority of my major on poetry. Now I use the tools — the analytical eye, the ear for the music of language — but for other purposes.

Louise Glück won the Nobel Prize in Literature a couple weeks ago. She was one of my favorite contemporary poets in college. But when I read the announcement, I realized I couldn’t even remember the titles of any of her poems.

That guilty thought makes me want to sit myself down and force-feed myself her collected works until I get it again.

But is laziness really the root of the problem? Reading, or ideally listening or reciting, reminds us how subtle language can be, how it can be an instrument in the musical sense, not just a tool. It’s easy to become numb to that in the digital world, when we all use words like they grow on trees.

Or like they don’t — more than laziness, the lack of interest can stem from the extreme efficiency of online reading habits.

That’s fine, and it’s an effective way of communicating for everyday use.

But there are other instruments, and other venues, and unfortunately it’s possible to lose interest in them after becoming accustomed to the numbing digital flow of a social media feed and its rivers and webs of links.

This is one source of the anxiety of social media, with its constant news coverage and discussion. Human communication will always affect us emotionally, whether in print or online, political tweets or poetry. But online, it’s always trying to drag us somewhere else. And before we have a chance to respond, it’s on to the next thing.

Poetry, like music, can give shape to thoughts and emotions in a way that reshapes and reorders time. In returning to Glück’s poetry, I was struck by her seasonal writings, because they reminded me of another timeline outside the Twitter feed and the impending election.

Before November 3, there is “All Hallows”:

Even now this landscape is assembling.

The hills darken. The oxen

sleep in their blue yoke,

the fields having been

picked clean, the sheaves

bound evenly and piled at the roadside

among cinquefoil, as the toothed moon rises:This is the barrenness

of harvest or pestilence.

And the wife leaning out the window

with her hand extended, as in payment,

and the seeds

distinct, gold, calling

Come here

Come here, little oneAnd the soul creeps out of the tree.