Friday

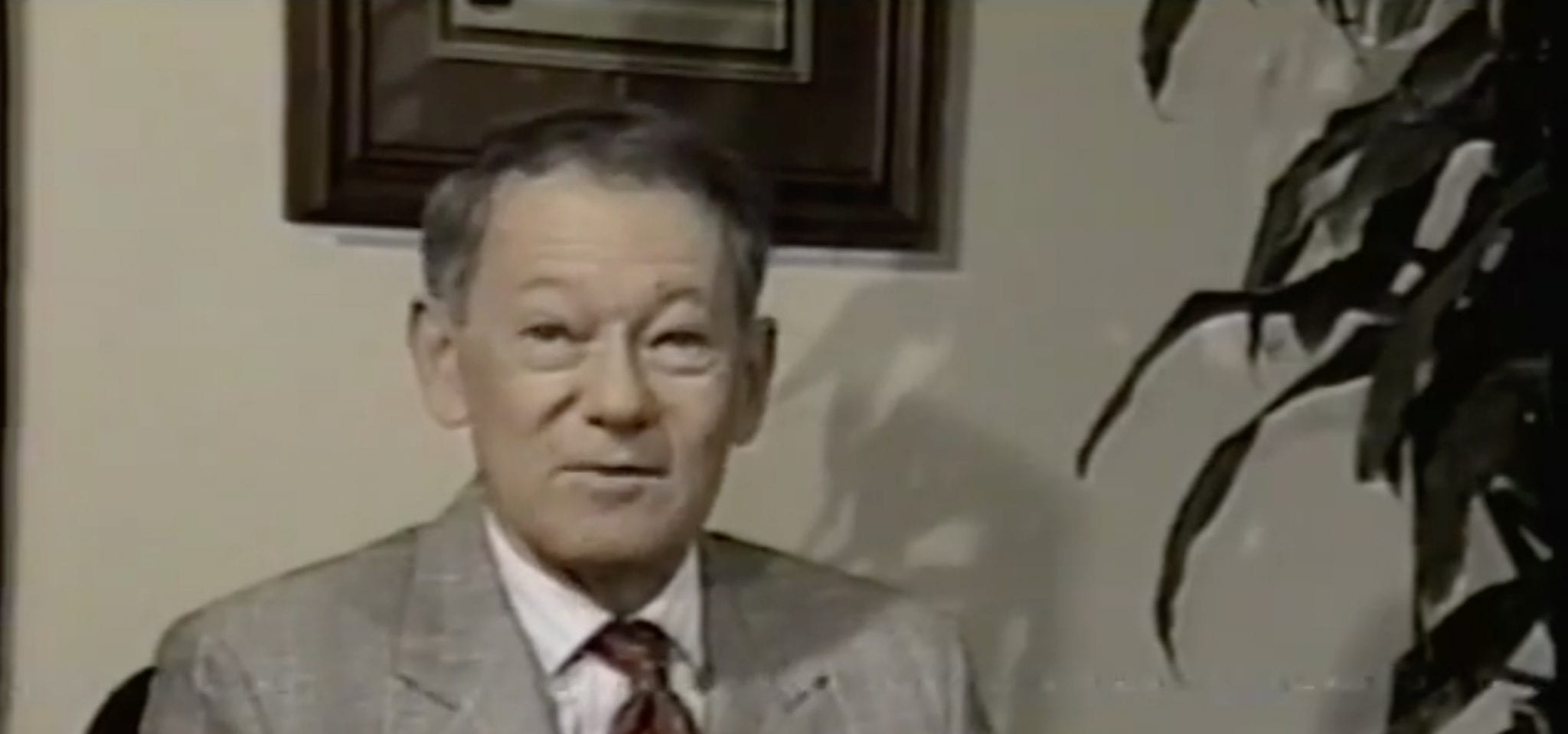

Al Burton is dead. Al died Tuesday morning. His beautiful daughter, Jennifer, called me with the horrible news. Al was 91 and had been in failing health for some time, barely able to follow what was going on around him. But he still smiled at me and at his glorious wife, Sally, when I was there.

Al was my best friend almost from the first second I met him at a meeting of the Aspen Institute “studying” pop culture in 1975. Some of the other participants in the meeting were condescending to Al (and to me), so we were immediately bound to each other by the gift of conjoined attempted humiliation.

After one session, Al asked me to stay behind and watch while he played a VHS of his and Norman Lear’s new experimental show, “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.” It was a satire of a soap opera, and it was brilliant from start to finish. I loved it, and I loved and worshiped Al. He was hilariously witty and extremely friendly. His wife, Sally, was around him 24/7. She loathed RN, but otherwise we got along famously.

In fact it was because of Al’s extreme kindness that I gave up my West 66th Street apartment and moved to sunny Cal. He and I were inseparable pals. We worked on a script together about teenagers’ obsessions with buying things. I wonder where it is. I have no idea.

Al and Sally and I went out almost every night for food, usually at what was then the hippest place in town, Ma Maison, near Melrose and La Cienega.

Al helped me get a gig writing and “producing” a picture book about the making of “Mary Hartman” and other projects at Norman’s company, “Tandem/TAT.”

Day after day we would feast on Al’s favorite luncheon, two kosher hot dogs on a china plate in his office. We would laugh and laugh at the ridiculousness of Hollywood life — but we were parts of it, too. Al was my Jay Gatsby, showing me the lushness of life in Hollywood — just what I wanted to see. Especially after the horror of taking the subway to my office at the Wall Street Journal and working with newsmen, the coldest of the cold. I can put it really simply, which is best for a simple mind like mine: When I was in New York, I took the nearest taxi to wherever I was going. When I moved the L.A. I bought a Mercedes coupe. Big difference.

Norman Lear’s office was right across the reception room from Al’s, where I hung out and Norman was unbelievably good to me as well. He often invited me in to hear him brief writers and directors on their work. At one point he had eight or nine shows on primetime CBS, and he knew how to make people laugh. He also knew how to make people take a look at themselves and smile.

It’s difficult to say how or why people become incredibly close friends. It’s almost like a love affair. Something clicks and whaaam, you have a close friend. That’s how it was with Al and Sally and me.

When I first met Al and Sally, they had a home in Beverly Hills with a swimming pool. I could occasionally swim there along with Al. One day a bee came out of nowhere and stung Al on his forearm. Al was allergic to bee stings and became upset. I took my fingers and pulled out the stinger. Al was in tears of gratitude.

On many other occasions I would get an offer for a script. I often thought the offer was too low. But Al would almost always say, “T-t-t-take it,” by which he meant, “Take it in a hurry. It’s real money, not promises.” I would cry with relief that Al had given me such sensible advice.

Al was a producer of teen fashion shows and sitcoms. These are difficult jobs, but they’re not rocket science. Then one day about 20 years ago he came out of the blue with such a brilliant insight that it ripped my skull open.

I had been asked to be the narrator and producer and co-writer on a film attacking academic suppression. In this case, the suppression was about Darwinian evolution. If you were a professor or a teacher of any kind and you spent even an instant questioning Darwinian evolution, i.e., the idea that life might have not evolved over billions of years but instead might have been created by an Intelligent Designer, you could and would be fired at once. The theory of Intelligent Design went on to say that the Intelligent Designer (He or She) then immediately set up the earth and the universe to run by that intelligent design.

For even questioning whether such a thing was possible, you got fired and sneered at for the rest of your life.

I asked Al what he thought about the subject, and he came out with a super brainstorm. “There has to have been Intelligent Design at least of something,” said Al. “After all, man evolved and so do fish and monkeys and plants.

“But the laws that govern the universe, the laws of gravity and of thermodynamics have stayed the same forever or else we and our whole universe would come crashing down into chaos. So they must have been designed by someone real and permanent.”

I believe that’s the smartest, most revolutionary idea I have ever heard.

I accepted the assignment and got yelled at and criticized when my work came out. But Al and his Theory of What’s Real and What is Not still seem to me to be right.

I could tell you other brilliant things Al said to me. Many, many years ago, Al and Sally and I were having dinner at La Scala in Beverly Hills. We were talking about Norman Lear’s genius, as we often did.

“Isn’t it lucky for Norman that he was born with a trait of getting along well with others, of making friends so quickly and decisively?” I asked.

Al looked at me incredulously. “He wasn’t born that way,” Al answered. “He shaped himself into a loving, lovable guy. He did it to himself. And anyone who really wants to work at it can shape himself similarly. It’s work, but it’s work well worth doing.”

This was a brilliant insight by Al — one of many that changed my life. I decided I would try to be more like Norman and Al and less like the sulking baby I had been. It has worked well. It’s a lot like How to Win Friends and Influence People but with examples extremely close at hand.

Time passed, as it will. Al had always had a wildly diverse career with shows ranging from “Teenage Fair” to “Miss Teenage America” to “Hollywood A Go-Go” (where The Rolling Stones made their U.S. TV debut. With Norman Lear, he worked on “Mary Hartman,” “The Jeffersons,” “The Facts of Life,” and more others than I can count. All successes, although “All’s Fair,” on which I worked as a consultant, could have been better. I had been hired to give advice on how a conservative columnist patterned after Bill Buckley would respond to his live-in girlfriend, patterned after Jane Fonda. I didn’t really do much except amuse the producers, who never tired of introducing me to the audience as “our resident fascist.”

In the mid ’80s or so, Al left working for Norman Lear and started producing his own shows at Universal. He had several smaller hits and one monster, “Charles in Charge,” starring Scott Baio as a babysitter for some teenagers.

Then Al had a brilliant idea: “Win Ben Stein’s Money.” It was a game show in which three people from “the street” (actually tested rigorously for weeks before they appeared on TV) played against me in answering questions of general knowledge. The trick was that when I lost (as I occasionally did) my losses were deducted from my pay. I was the host and a contestant, and my own small dollars were on the line for every question.

It was extremely stressful work. I played about 950 games over six seasons, and I eventually wound up winning more than 80 percent of them. I think that must be a world’s record for winning a game show. Needless to say, I was never given the answers or the questions in advance, and I was always in a frenzy of nerves before every game.

We had the incredible good fortune to hire Jimmy Kimmel, a local DJ, to be my co-host. That meant he asked the questions in the final round. He was funny! In the middle of the final season, after we had already won six or seven Emmys for writing and one for best host and co-host, Jimmy announced that he was quitting to host his own show. I had a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach when I heard it.

I knew very well that while I had the answers to many questions, the belly laughs came from Jimmy.

He’s the smartest, funniest guy on the air.

So, I did a talk show, “Turn Ben On,” for three seasons on Comedy Central, with Carl Bernstein and John Mankiewicz playing guest guitarist. (Yes, scion of the fabulously talented Hollywood Mankiewiczes.)

I did my commercials and speeches, and Al Burton was always available for a lighthearted lunch. How I miss those meals! For good reason, my lunches with Al were like my lunches with my father. Sitting before a roaring fire at an old English tavern on a blasted heath, swapping insights from science and economics to what comedian had the best routine on TV that week. Al was only 17 years older than I am, but he was also always a father figure, just as Sally was a mother figure — wildly politically in another gear, but in person as loyal a friend as anyone could want.

(When I first moved to Hollywood I had to have hernia operation on my ample abdomen. Sally swore to stay by the OR door until the surgery was over to make sure I was alive and well. She did it, too.)

About 10 years ago, Al moved with Sally to San Mateo to be near their lovely daughter, Jenny. I well recall bidding farewell to Al and knowing my life would not be the same for my wife and me. I visited Al many times (not as many as I should have done) and prayed for him and his family.

His health deteriorated badly, and soon he barely knew me when I came to visit. He was still always encouraging and wise, though. The last brilliant thing he ever said to me was after I asked him for advice I could carry in my heart when I was old and feeble.

“Yes,” he said. “Peace is a good thing.”

Now, Al is gone. I hope I will see him in the afterlife at The Rainbow Bridge, where we meet all of the people and pets we loved in life and stay with them at that roaring fireplace forever. I have read and reread this column, and I see I have not really gotten across what I wanted to say. I loved Al. I loved him and he loved me. When I moved out here on June 30, 1976, Al met me at the majestic LAX with four beautiful teenage actresses with captions that read, “I’m Benjy’s.” When I went to work at the Wall Street Journal editorial page, Al treated me as if I were a king. There never will be another Al. He was my king. Blithe spirit of Hollywood. Best friend I ever had.