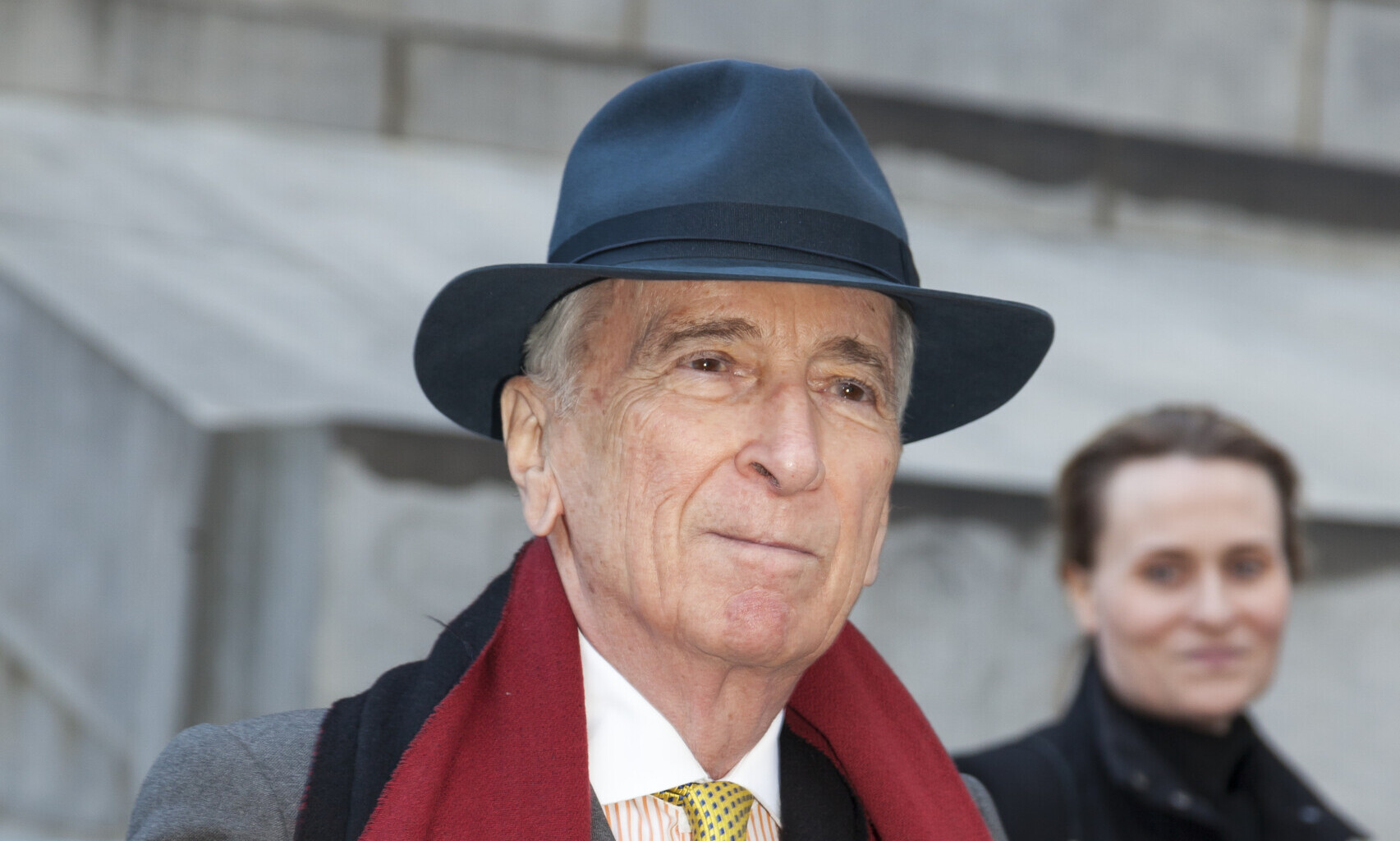

I have just finished reading the latest book by a man with gray hair, almost snow white, perhaps snow with slightly dirty car wheel tracks, with a prominent nose of undoubtedly Italian origin like his ancestry. He wears an impeccable charcoal gray suit cut to measure by the same man for decades, with a white shirt and a classic movie collar, and a yellow tie of the finest knit, which falls with the naturalness of an anchovy fillet on his chest, between the lapels of his jacket.

The man stands 5 feet 10 inches, 5 feet 11.6 inches when dressed in his impeccably hung dove grey Borsalino hat, the elegant gentleman weighs 161 pounds, 158 pounds fasting, and was born in Ocean City, New Jersey, 93 years and twelve days and six hours and forty-five seconds ago.

On one sunny blue-sky morning with two or three lone clouds to the northwest of the city, he was born to his mother Catherine, who was married to Joseph, a tailor who emigrated to the United States in the 1920s from Maida, a village inhabited throughout history by Greeks, Romans, Lombards, Byzantines, Suevi, and Albanians, in the province of Catanzaro, located at the tip of the boot that forms the shape of the map of Italy.

The man gets up every morning at 8:01 a.m. in his third-floor apartment in the four-story brownstone building on 109 East 61st Street, New York City, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. A building he bought outright in 1973 for $175,000, $50,000 of which went to repairs.

He walks slowly to the bathroom with first his right foot and then his left (he has two feet) at an average speed of 2.2 feet per second, which becomes 2.9 feet per second if he is really peeing himself, and slowly washes his hands and face looking much younger in the mirror than he did yesterday, when curiously he was younger, a few feet from where a few minutes later he will sit at his desk with a huge tray of succulent muffins and a thermos full of hot coffee to write fascinating stories that will keep you glued to the paper for hours.

The man who works on a page a day, first draft by hand, which brings him on balance between three and four hundred new words per day. He writes with the precision of a surgeon, or of an Italian tailor like his father, and who is the undisputed voice of what was called new journalism.

Yes, you guessed it, I’m talking about Gay Talese. And, although I deeply admire his way of writing, I can’t help making fun of his obsession, and that of all those in new journalism, for making every news report an endless succession of distances, speed, impossible-to-measure weights and measurements, colors and tones, exact postal addresses, proper names of background characters, and subplots several kilometers long with precise information about random people who are not involved in the story, and all the other flowery literary games that characterize his particular style.

I just finished reading his latest book, Bartleby and Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener, and I know absolutely everything that surrounded the figure of Frank Sinatra (his collaborators, his favorite foods, his disapproving gestures, his collaborators’ girlfriends, or the way his assistant walked), or every last detail of the fascinating story of the suicidal doctor Nicholas Bartha, that portly man, 5 feet 11 inches, with glasses, gray hair, formal bearing and a slight foreign accent, who had been born in Romania in 1940.

Gay Talese’s literary writing was a marvel, and remains so today, although I wondered how today’s generations accustomed to 10-second TikTok videos could stop to read the exact dimensions of each of the rooms in the beautiful 19th century neo-Greek residence at 34 East 62nd Street, between Madison and Park Avenues, which Dr. Boom, as he was called by the press, blew up to avoid having to sell it to pay his ex-wife the $4 million that was imposed on him by the courts in the divorce proceedings that began three years earlier.

I am very sorry that the new generations cannot enjoy Gay Talese’s prose because of sheer impatience. Although he also makes me anxious at times with the precision of his descriptions, I recognize that he has been a great help to me, especially in the writing of my novels. With the tendency I have to fixate only on emotional details, or humorous caricatures, dwelling even partially on the details as does the last living gallant of yesterday’s journalism has helped me to paint better pictures in my fiction writing.

Now that journalism moves between memes and clickbait, I miss those texts of yesteryear that made you really visualize each chronicle. I myself, after finishing the book, can’t wait to visit the place where Dr. Boom’s elegant townhouse on the Upper East Side was located and say a heartfelt prayer for the eternal rest of the suicide victim, and another for the eternal immortality of old masters of journalism.

READ MORE from Itxu Díaz:

JD Vance: An Intelligent Speech for an Artificial Audience