God said, Let there be light, and there was light.

In the very first paragraph of the Book of Books, the primordial darkness and incoherence is mastered by words, the divine speech. As last of the creatures, that speech devolves upon us. More than anything, the supremely powerful use of words is what distinguishes us from all other creatures.

Genesis has it that we humans are made in the divine image, and making it reasonable that we should apply what we know about God from His words to our own use of language.

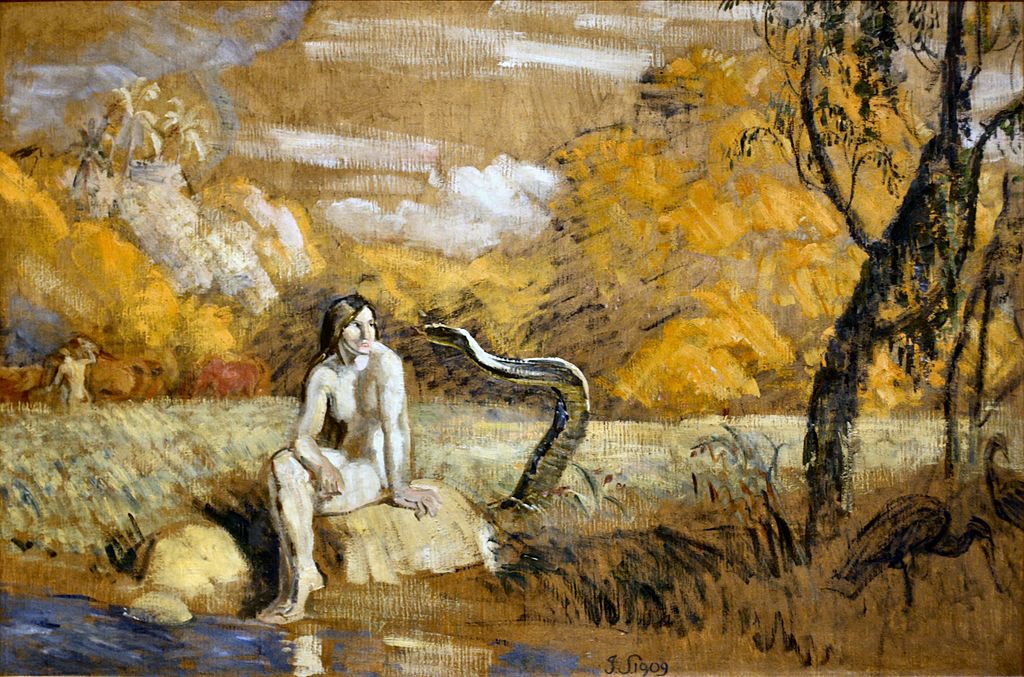

The snake in the Garden portrayed himself as nobly freeing Eve from a despotic deity. The rabbis of old taught that someone seeking to disqualify others will do so by accusing them of the disqualification he himself has imposed.

An old Jewish tradition points out how Eve stumbled in her carelessness with God’s words. The snake provoked her into talking about how God had forbidden her eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil on pain of death. She told the snake that God had commanded her and Adam “not to eat from it and not to touch it,” when God had never prohibited touching. Seizing the opportunity, goes the tradition, the snake pushed her against the tree and exclaimed, “See! You did not die from touching it. You won’t die from eating it, either!”

Beginning with that careless imprecision, the words got worse as the first couple used words to hide the truth and then, when caught, used words to rationalize and blame rather than to cleanse the stain and restore the truth. They had unhitched the supreme power of words from the beneficence with which that power is always coupled in God.

So much of the Bible and of the traditions that have accompanied it through the millennia is about the need for power always to be yoked, exactly and precisely, to beneficence. When power is entirely devoted to the good of the other, we have that love that Leviticus requires of us, that “great rule of the Torah” as Rabbi Akiva put it 1,900 years ago.

This great tradition of the Word is not averse to sharp questioning and vigorous debate. Abraham and Moses famously challenge God’s commitment to justice with sharp words, and they are not reproved by God for doing so. When Job in his agony questions God in strongest terms and is censured for it by three friends who toe the orthodox line, God says to one of those comforters, “I am angry at you and your two friends, for you have not spoken about Me properly, as did My servant Job.”

There is a direct connection between this great theme of Biblical culture and the development of political guarantees of liberty of speech and religion. If speech is honored and is used in pursuit of truth and of goodness worthy of its power, then even fierce debate must be allowed. A rabbinic teaching looks at the debate between two schools of teaching and declares that their words will last, since their debate was not self-serving but for the sake of Heaven. As a counter-example, they point to the debate of Korah and Moses, in which Korah’s skillfully provocative arguments were meant to hide an unjustified attempt to usurp Moses’ legitimate power.

There is an ever-broadening consensus in America and other lands that have tasted freedom of expression that we must stand up and defend our great national and international conversations from those who would use their power of expression to shut down the voices of all who differ from their version of right doctrine. It is a welcome development, if only because it already shows that this defense is already bringing together a widely diverse group of people.

For we have been sinking into a kind of national psychosis, losing our ability to deal sanely with people who disagree with us. Absurdities have been taken as commonplace in every sphere of public life. As Yeats warned, the center does not hold, and mere chaos reigns where there once was trust and common purpose.

But many public figures have been effectively putting forth an alternative. Bari Weiss has not only effectively criticized the Savanarolas at the New York Times, but through Common Sense at Substack, given an effective counterexample of how to write and edit honestly and effectively. Jay Bhattacharya and his noble colleagues have persisted in what is now a widely accepted argument against the fascistic spree of government doctors and tyrannical political opportunists who used unconstitutional power to destroy all effective criticism of their appallingly damaging policy choices — and did so by aiming to destroy the reputations and the lives of the critics.

Yet the masters of malevolent speech long ago learned that they can long avoid detection by sowing confusion. The snake in the Garden portrayed himself as nobly freeing Eve from a despotic deity. The rabbis of old taught that someone seeking to disqualify others will do so by accusing them of the disqualification he himself has imposed. Or, as a modern maxim puts it, “Accuse your enemy of what you are doing in order to create confusion.”

How can we see through manipulative speech and protect ourselves and our community from manipulation by clever dissemblers?

I think Churchill is useful here, as in so many issues in public life. Observe his thought here, as he was establishing a government capable of overcoming the deadliest danger free societies had ever faced.

The challenge in a moment of national emergency is how to bring a unified, effective, and powerful response to a terrible danger. For that, a government has to have robust debate to make sure its actions are based on the best intelligence, the most exacting analysis, and the most robust and brilliant insight. To that end, Churchill gathered around him in high office members of all the three major parties, including those whom he had at times vigorously opposed in public debate.

Yet one thing he would not have. He described his opposition to the position of Minister Without Portfolio, which is someone who is a part of the governing cabinet but who has no responsibility for administrating any department of government. Churchill saw in this the destruction of the great principle that power and responsibility had to go together precisely. Too little good can be expected of having someone who could exert the power of speech at the highest levels of power but was not accountable for anything at all. The result at best would be, as Churchill put it, “brooding in ignorance on the work of others.”

Take this insight and use it. Is someone using the power of language without accepting responsibility for any results? Such a person’s words must be tested severely and do not command trust on their own.

About forty years ago, in an essay titled “Standing By Words,” Wendell Berry wrote:

We take it for granted that we cannot understand what is said if we cannot assume the accountability of the speaker, the accuracy of his speech, and mutual agreement on the structure of language and the meaning of words. We assume, in short, that language is communal, and that its purpose is to tell the truth.

In an era of talking heads and faddish and fungible principles, the old idea of standing by words sounds quaint. But it may not remain that way, as more and more people see the grave harm inflicted on our nation and on the human community everywhere by words that are not accountable, but are flung at others without care of their consequence to anyone or anything.

Tyrants of every stripe use words only to manipulate and to maneuver, not to discharge a responsibility to others, be they family, friends, country, or God. Our freedom requires the conversation of those who see language as the cardinal instrument of creation, in which we work together, accountable to every other user of language for keeping our words truthful, understandable, and perhaps even beautiful.

Test the words of those you hear and read by this measure. Give trust to those writers and speakers whose words put their trust in you. As citizen sovereigns of our nation, this is our urgent duty.

Image: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.