“And bid the world Goodmorrow, and go to glory home!”

– Emily Dickinson

I am writing about this because it has been the only thing on my mind during the last few days.

On Jan. 13, Terry Teachout, the theater critic of the Wall Street Journal and a good friend of mine for decades, died suddenly at age 65. His death came as a shock, in part because he was so full of life, in love with it, enthusiastic about it. He filled every day with constructive activity and flew across the country every other week to see plays. We lived on opposite sides of the Atlantic, but, thanks to social media, I was able, like hundreds of others, to follow his life almost day by day, sometimes almost hour by hour. When he died, the news spread instantly, communicated online by hundreds of grieving friends and colleagues.

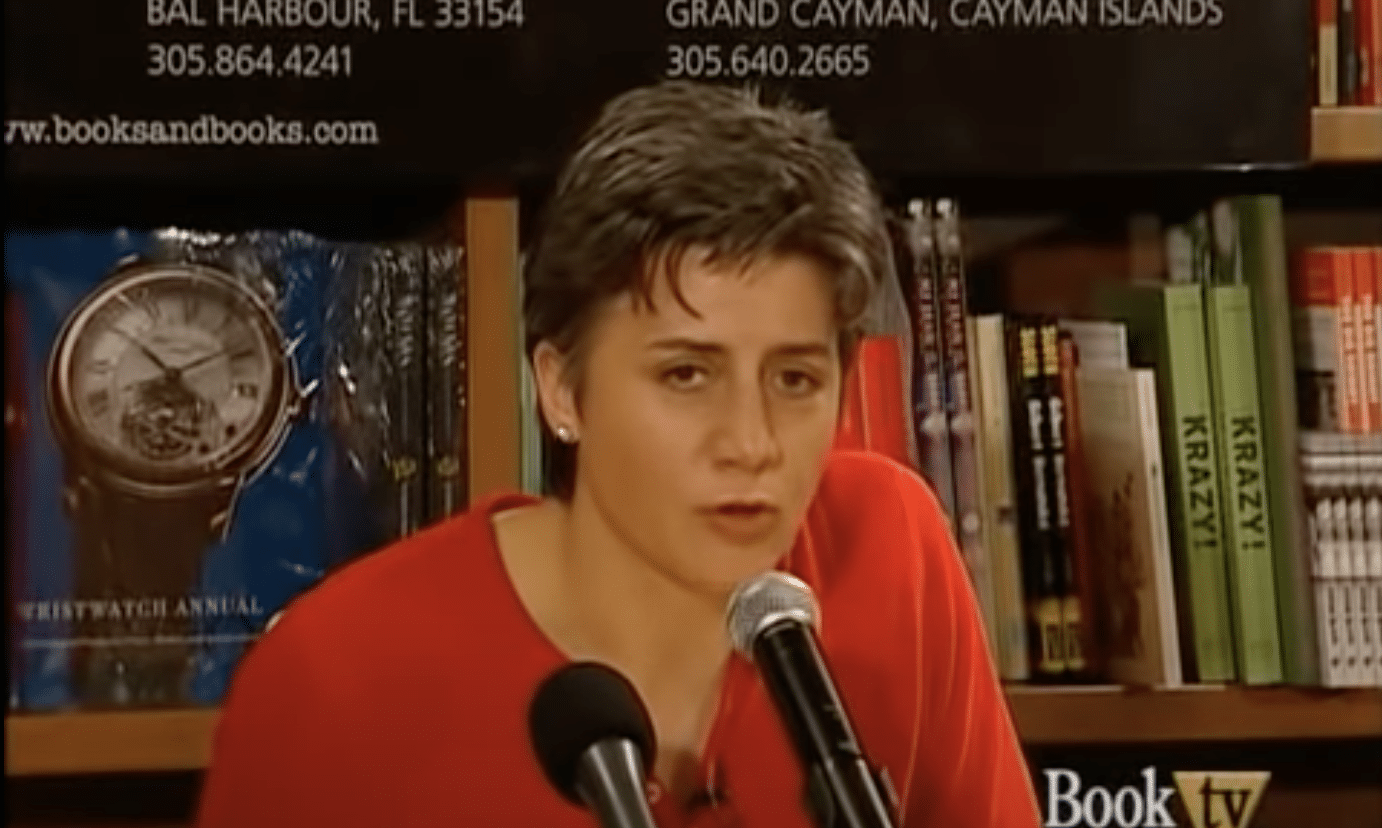

On Aug. 18, I was stunned to learn of another friend’s death. I had met Norah Vincent in the mid-1990s when she worked at the Free Press, which at the time was preparing for publication a collection of essays that I edited, Beyond Queer: Challenging Gay Left Orthodoxy. It turned out that Norah had written a piece that was perfect for the book. In it, she assailed the humorless “groupthink” and “angry ghettoization” that, in her view, marred the so-called “lesbian community.” “If lesbians truly want equal rights and equal treatment,” she concluded, “they should step into the real world, make a case for their humanity first, and, above all, learn to take a joke.” Gutsy words in 1996. But then, Norah was as gutsy as they come.

I snapped the piece up; by the time the book came out, Andrew Sullivan, also impressed, had run it in the New Republic.

For me, that piece, entitled “Beyond Lesbian,” was the beginning of a friendship; for her, it marked the start of a remarkable — and singular — writing career.

When she eventually wanted to write a book, I hooked her up with my agent, Eric — who dropped me like a hot potato shortly thereafter, but that’s another story. Nobody could’ve imagined the book she came up with. For a year and a half, she went undercover as a man, joining a bowling club, going to strip clubs, and exploring straight-male society from the inside. Since she was tall and slim-hipped, it wasn’t an impossible masquerade to pull off; indeed, even without the fake facial hair and other tricks that were part of her disguise, she was often mistaken for a male. (Once, having lunch at Parnell’s, an Irish bar on First Avenue that used to be one of my hangouts, I cringed when the waitress addressed us as “gentlemen.”)

Norah’s main takeaway from her time as a man was that men aren’t the patriarchal monsters conjured by many a feminist imagination. Even though they’d suspected her alter ego, Ned, was gay, and even though he was a terrible bowler, her bowling buddies had welcomed her into their circle and proven to be good friends. What struck her most about them was their essential loneliness: “Men are suffering,” she wrote. “They have different problems than women have but they don’t have it better. They need our sympathy, they need our love, and they need each other more than anything else. They need to be together.”

Published in 2006, Self-Made Man: One Woman’s Year Disguised as a Man became a big bestseller. Shows like ABC’s 20/20 devoted extensive segments to Norah’s bravura deception. What got less attention was the fact that her imposture cost her a great deal psychologically. By the end of the charade, she was “passively suicidal” and committed herself to a locked mental ward. The terrible truth was that she’d suffered for a long time from bouts of hypomania and depression and was on antidepressants. Self-Made Man might’ve been a tour de force, but the year and a half of deceit that made it possible could also be seen as an act of profound self-destructiveness.

Her next book idea was a step even further down that dangerous path. When I heard about it, I thought: No. No. No. Issued in 2008, it was entitled Voluntary Madness: Lost and Found in the Mental Healthcare System. The premise was simple: Over the period of a year, Norah put an antic disposition on, checked herself into a series of psychiatric institutions, and took notes.

I knew that Self-Made Man had done a number on Norah psychologically. Voluntary Madness seemed destined to do even more damage. And it did. And of course, Norah was smart enough to know exactly what she was doing.

By this time, I’d been living in Europe for years. In 2011, when I spent a few months in New York, I repeatedly tried to meet up with her, but without success. In my emails, I find a message from her dating to that year:

I suppose you’ve left the city by now, haven’t you? I’m sorry to have been unable to get it together for a dinner. I’ve been nuts these last few weeks. Just finishing my novel and doing my editor’s changes…. I’m sorry again. I hope you can understand. Sending love, Norah.

The novel in question was Thy Neighbor: A Novel (2012), which somehow I never got around to reading. It was followed in 2015 by another, Adeline: A Novel of Virginia Woolf. Knowing Norah, I was alarmed when I read what this one was about: It re-imagined the last part of 20th-century writer Virginia Woolf’s life, including her suicide.

No. No. No.

From what I heard, she was crushed by the novel’s poor sales. She was even more crushed when Eric dumped her, as he’d dumped me.

In any event, we lost touch. We’d been Facebook friends; only now do I see that at some point she unfriended me.

And then, on Aug. 18, came the inevitable Times obituary, which reported that Norah had died in Switzerland and that it had been a “voluntary assisted death.” It had happened on July 6, six weeks and one day before the obituary appeared.

“Voluntary assisted death”?

I immediately emailed a longtime friend and editor of mine who’d been close to Norah for years. What did he know about this? Had Norah chosen death because she’d been terminally ill? Or … ?

He didn’t know. Norah, he said, had thrown him out of her life “4 or 5 years ago.” At that time, he added, she’d been a terrible mess.

I posted Norah’s obit on Facebook. So did another friend and editor of mine, John Podhoretz. “I remember Norah as a young person,” John wrote. “She seemed like the unhappiest human being I’d ever met.”

Was she? In a way, it rings true. And yet I can still hear her laughter.

On Facebook I found the New York theater director who was identified in Norah’s obituary as her ex-partner. (It turned out that we had one mutual Facebook friend: Terry Teachout, of course.) We had an illuminating Facebook chat that I’ll keep private. Suffice it to say that she wasn’t privy to the details of Norah’s death, either.

I reread Norah’s obituary. What I’d somehow breezed past the first time around was that her death had been reported to the Times by Justine Hardy. Could this, I wondered, be the same Justine Hardy whom I’d lunched with over the years at the annual Oslo Freedom Forum? Justine Hardy, a British writer based in London and India, who’s widely lauded for her decades of work in South Asia as an “integrated trauma therapist” and her involvement with the Healing Minds Foundation, which addresses “mental health care and education in conflict and crisis situations”? Justine Hardy, whose late father, the great classical actor Robert Hardy, indelibly stamped himself onto my mind when, as a 14-year-old boy, I saw him in Elizabeth R as Elizabeth I’s beloved courtier Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester? “You came, but too late,” Hardy says to Glenda Jackson (Queen Elizabeth I), who’s failed to show up on time at a chapel where they’d agreed to wed clandestinely. “You waited,” she replies, “but not long enough.” Why did those simple lines stick in my mind? Why do they still haunt me, so many decades later? Why do they now seem to have something to do with Norah’s story?

I wrote to Justine. She replied almost at once. “Norah and I had a long friendship,” she informed me, “and towards the end of her life I had become the only person that she had remained in contact with.” Later, in an hourlong Zoom call, Justine explained that they’d met when Norah was in London promoting Self-Made Man. The friendship had taken off from there, until, in her final journey, Norah had flown from New York to London and, from there, with Justine (who is straight), to Switzerland. To Basel, specifically.

I’ve never been to Basel. Long ago, as it happens, the maternal grandfather of one of my most cherished long-term friends — somebody, in fact, who played a key role in my life — was president of the University of Basel. (I mention this seemingly irrelevant fact only because so many of the details of this horrible story seem almost designed as reminders of what a small world this is — of how intimately connected we all are.) It was in Basel, at a “clinic” called the Pegasos Swiss Association (pets welcome), that Justine witnessed Norah’s death. She wrote me: “Norah left a ‘legacy will’ in which she requested that I write about what happened, and about her wish to die because, well, in true Norah fashion, she said that she wanted to become a ‘Death doula.’ I think you knew Norah well enough to know how wry her smile was when she was saying that.”

I had to look up “death doula.” From Wikipedia: “A death midwife, or death doula, is a person who assists in the dying process, much like a midwife or doula does with the birthing process.”

Justine sent me the account she’d written of Norah’s last days. It is a beautiful and powerful — and profoundly chilling — piece of writing. Before contacting Justine, I’d tried to imagine what it might have been like for Norah to make that trip from New York to Switzerland, going through every familiar, mundane, quotidian step — locking her apartment door, finding her seat on the plane, checking in at the hotel — all the while knowing what it was all leading to. I couldn’t begin to imagine what that was like, that journey to nirvana. What’s chilling about Justine’s account (which appears in the current issue of The Oldie) is precisely that mundanity. On the way to meet the psychiatrist who will determine whether Norah is compos mentis, and thus legally qualified to choose extinction, Justine and Norah get stuck in traffic. On her last morning, Norah eats a hearty breakfast.

How to even process such material? How to understand a mind that plots its own destruction in the midst of the dailiness of life? For those of us who cherish life and who, as we age, increasingly fear death as we see it looming ahead of us, growing ever larger in our field of view, what could be more terrifying than the idea of scheduling an appointment with a psychiatrist in England, and then with a clinic in Switzerland, with the end goal of being carried out feet first?

After I read Justine’s piece, I pondered: Could it be that Norah, who’d attempted suicide at least twice, had been hearing the voice of death calling to her for so long that perhaps it felt, in the end, like an old friend?

Then Justine wrote back. It had been important for Norah, she told me, that it be understood “how profoundly she wanted to die.” She continued, “It took me too many years of our friendship to realise that she really did have the same romantic relationship with death as Emily Dickinson, grandiose as that may seem.”

Not a friend, then, but a lover.

How curious that she was so eager to shuffle off this mortal coil — as if life meant absolutely nothing — yet at the same time urgently wanted to leave a record, in this veil of tears, of her love of death. Perhaps it was the writer in her. John Updike once wrote about how much it meant to him to see his collected works lined up on a shelf, the spines (after the dust jackets were removed) all identical in design. For many writers, there’s at least some degree of comfort in the idea of being survived by one’s oeuvre.

But why would someone enamored of death give a toss about sending a postmortem message to the living?

I’ve mentioned Terry. He was the opposite of Norah. He loved life, cherished it, reveled in it, welcomed it with open arms every day, and took care not to waste a minute of it. His second wife, Hilary Dyson, suffered from a rare progressive disease, pulmonary hypertension, that caused her increasing pain and debility, and every day for years they struggled mightily together, against great odds, to keep her alive and to give their shared life as much meaning as possible. Hilary died in 2020, and, at the end of last year, having found a new love, Terry gave thanks on his blog for “the return of good fortune to my once-charmed, twice-blessed life” and said that he looked forward to the abundance of life that awaited him in 2022.

Two weeks later, he was dead.

For Terry, hope sprang eternal. Emily Dickinson called hope “the thing with feathers.” Norah had hope, too. But her hopes, as it turned out, didn’t concern the things of this world. Instead of fighting to stay alive, she chose self-slaughter.

I’m the son of a brilliant doctor who ardently believed in battling death to the very last. When I was a kid, he kept giving me books that captured his view of medicine’s sacred mission. One was Morton Thompson’s Not as a Stranger (1954), in which, refusing to let an extremely old and sick hospital patient pass away quietly and comfortably, a noble-minded young doctor works feverishly all night to help him make it to another morning. Another was a 1941 novel by Frank G. Slaughter entitled That None Should Die.

And yet of course we all die. And what good, in the end, is the terrible fear of death? I remember that, when my father’s 90-year-old mother, who’d been mentally lost to us for almost a decade, was dying a long and painful death at Lenox Hill Hospital while my parents and I sat vigil, dulling our own pain with jugs of vodka, he astonished me by saying perhaps the very last thing I’d ever expected to hear him say: He could, he admitted, understand why some people supported the right to euthanasia.

Still, some things defy understanding. A romance with death? For most of us, I think, the idea is beyond comprehension. Then again, it wasn’t alien to Keats, who wrote:

for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain

Another romantic-era poet, Thomas Chatterton, who committed suicide in 1770 at the age of 17, is far more famous for his death — and his love of death — than for his poetry. But the suicides that seem more to the point, where Norah is concerned, are those of the women whose poetry she and I read when we were students and whose deaths, at the time, still felt very recent. Anne Sexton, for one, who returned to her home in Weston, Massachusetts, after a delightful lunch with fellow poet Maxine Kumin and turned on her car’s ignition in her closed garage. And, of course, Sylvia Plath, who, while her two small children slept elsewhere in her house in Primrose Hill, London, turned on the gas and stuck her head in the oven. Plath wrote:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.I do it so it feels like hell.

I do it so it feels real.

I guess you could say I’ve a call.

So many of the modern American poets whom I studied in graduate school were suicidal that one of the books on the syllabus was Al Alvarez’s The Savage God: A Study of Suicide (1971).

But then, committing suicide by oven gas in one’s kitchen or by carbon monoxide in one’s garage is different from doing it at a clinic in Switzerland. What to make of that choice? Why didn’t Norah just do it cheaply and simply, instead of dramatically and expensively?

Discussing Norah, my partner raised one point: “There’s something narcissistic about being a writer. What if she’d been a nurse in a children’s cancer hospital?” Might that have saved her life? Could it be that her real problem was excessive self-absorption, a lack of perspective? What if she’d been a peasant in Botswana or Guatemala? What if she’d had a pet to feed? Or do such questions indicate a total lack of understanding?

Enough. Let’s just close with this. On July 6, after downing her very last breakfast and taking her very last trip to the loo, Norah, according to Justine’s account, went with her to the clinic, to a “cool, white room” where Justine took out her cell phone and scrolled to the music that Norah had already chosen as the soundtrack of her demise: Nina Simone’s “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free.” According to the schedule she’d set, her death was a few minutes away. She asked what time it was.

“The time,” replied the anesthetist, “doesn’t matter now.”