In lieu of bleeding-edge, blow-by-blow analysis of initial reaction, here is a closer look at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) report for March. The 88,000 new jobs created last month fell short of the 190,000 jobs that economists polled by MarketWatch expected; on the other hand, those economists thought unemployment would remain at 7.7%, but it fell to 7.6%. January and February job figures were also revised upward by about 30,000 each. Making sense of these numbers is frankly a matter of interpretation, but the labor market has clearly yet to recover from the Great Recession.

Unemployment and labor force participation rate data are easily accessible, but what do these terms actually mean? The labor force essentially refers to Americans 16 years of age and older who held or were seeking employment at the time of an official BLS survey. Thus the labor force participation rate excludes individuals who have given up looking for work, generally referred to as “discouraged workers.”

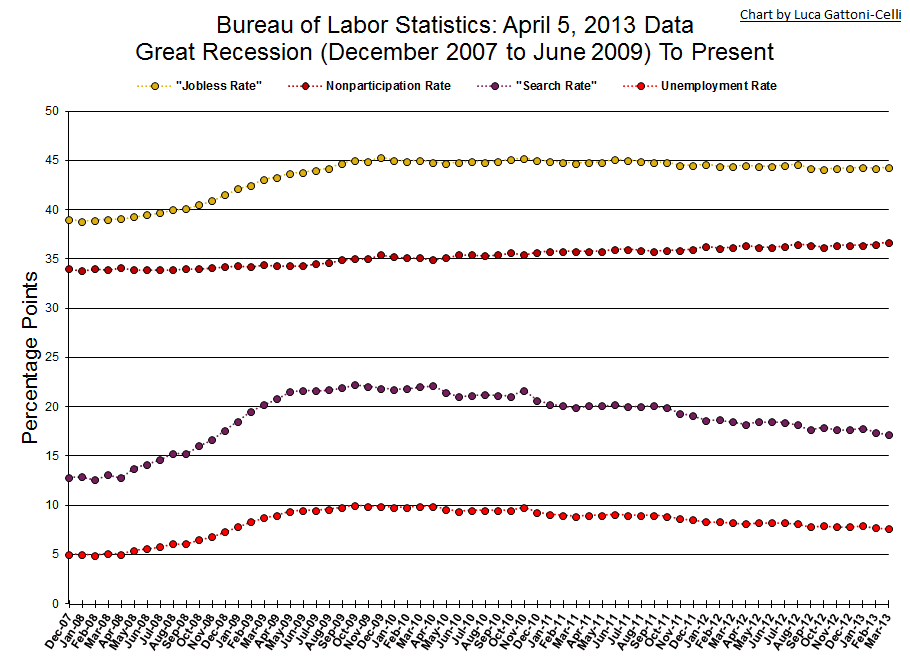

Careful observers note that the labor force nonparticipation rate increased from 36.5% to 36.7% in March, easily accounting for the reduction in unemployment. Labor force participation has sunk to the Cartesian levels of May 1979. Business Insider points to UBS’ Drew Matus’ longstanding claim that such trends are being driven by demographics, as Baby Boomers retire, but that seismic shift is only just begun. (The first official baby boomer, born just after midnight January 1, 1946, retired last August at the age of 66 years.) Discouraged or otherwise, workers have definitely been leaving the workforce, as illustrated by this chart:

The “Jobless Rate” combines the unemployment and nonparticipation rates to find what percentage of the labor force is, of all things, jobless. The “Search Rate” refers to the percentage of jobless individuals that is looking for work, which is to say unemployed. Its stagnation and decline since the technical end of the recession, June 2009, speaks to the difficulties we face, though a much broader decline in labor force participation has been occurring since the turn of this century. An optimist would posit that folks are simply interested in other pursuits, e.g. retirement. Setting aside the dour implications this theory holds for entitlement programs (the American birth rate recently fell below the replacement level), the fact remains that fewer and fewer folks are looking for work. It is difficult to be optimistic about the health of an economy in which this is the case.