On May 6, 2021, Willie Mays celebrated his 90th birthday. He is a baseball legend — and arguably the greatest player in the game’s history. He had a lifetime batting average of .302, hit 660 home runs, had 3,283 hits, drove in 1,903 runs, stole 338 bases, scored 2,062 runs, made 7,095 put-outs, and won 12 Gold Glove Awards in a career that spanned 22 seasons with the New York and San Francisco Giants and the Mets.

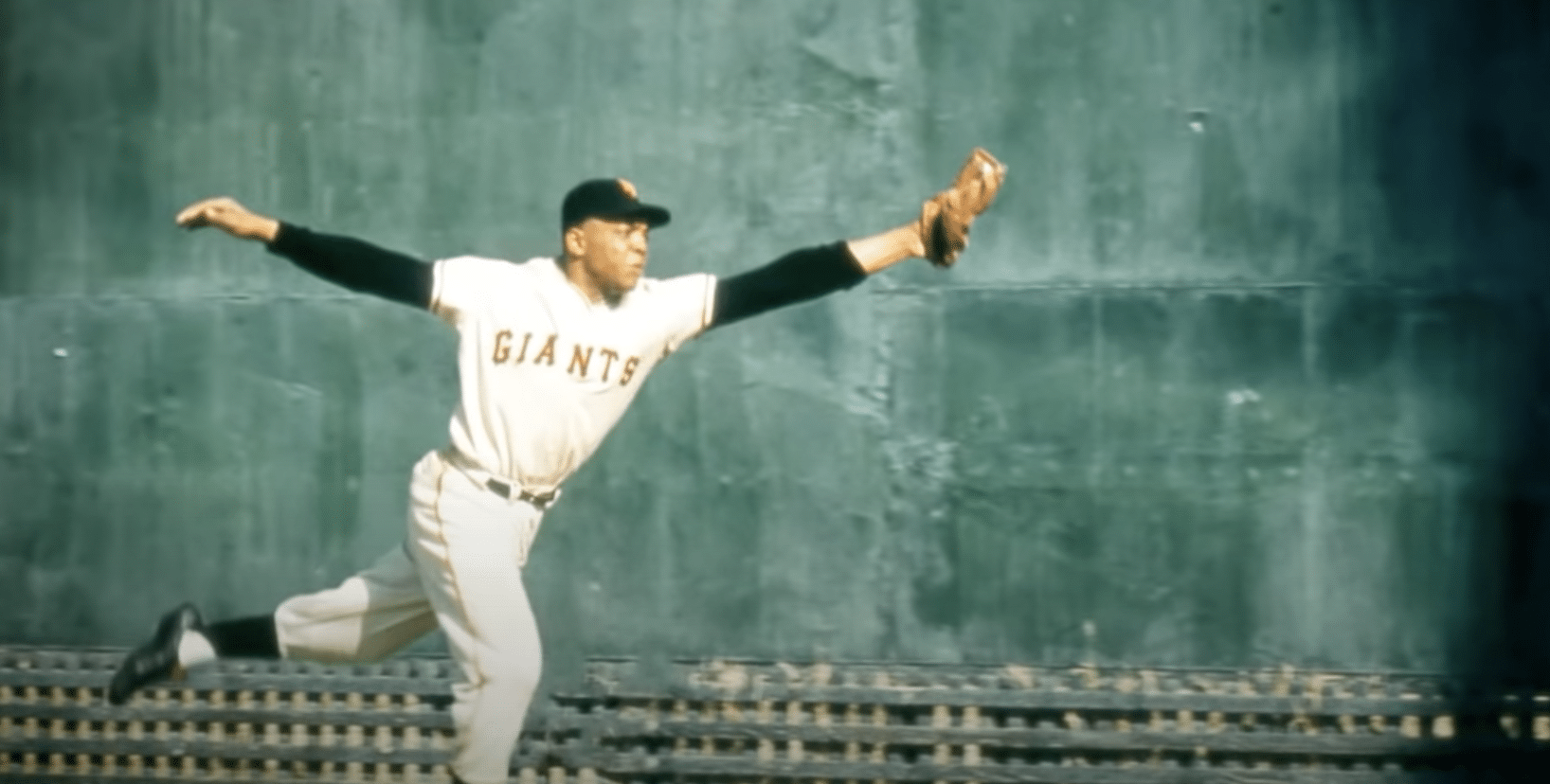

But the statistics do not tell the whole story of his greatness. Mays played the game with an exuberance and joy that thrilled baseball fans of all ages. I can still recall the way he rounded first base on his way to taking an extra base, appearing to magically glide along the infield dirt; or the way he pursued fly balls in center field, finishing the play with his famous “basket catch” (one announcer remarked that Mays’ glove was where triples died); or the way he seemed to effortlessly power home runs to all fields.

Mays also had a mental approach to baseball that has been described as “visualizing the whole game.” In his recent book 24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid (co-authored with John Shea), Mays explained it this way: “You’re knowing ahead of time what to do in all situations and making sure to be in the right place when you need to be.” He did this both on offense and defense.

On offense, it meant sometimes going from first base to third base on hits to right field, but other times holding at second base because of the game’s situation. At times it meant not stealing a base so pitchers would have to pitch to slugger Willie McCovey, instead of intentionally walking him. Mays sometimes deliberately swung and missed a particular pitch early in a game so that same pitch might be offered to him in a more important at-bat later in the game.

On defense, Mays positioned himself in center field based on his knowledge of both the hitters and his team’s pitchers. And he would move his right- and left-fielders accordingly. His brilliance in the field was never more evident than in the famous catch and throw he made in the 1954 World Series against the Cleveland Indians. It is a play that is still known as “the catch.” Cleveland’s Vic Wertz hit a ball to the deepest part of the Polo Grounds and Mays literally outran the ball, caught it over his shoulder while running toward the center field wall, and immediately wheeled around and threw a strike to second base, ensuring that a runner did not advance. Mays said he knew he was going to catch the ball as soon as it was hit, and he considered his throw more impressive than the catch. Sports author and Mays biographer Arnold Hano wrote an entire book about “the catch” called A Day in the Bleachers (1955).

Mays’ professional baseball journey began in the Negro Leagues, where he played for the Birmingham Black Barons. John Klima writes in his book Willie’s Boys about the time Carl Hubbell, the legendary left-handed pitcher for the New York Giants who famously struck-out “murderers’ row” (Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, and Joe Cronin) in the 1934 All-Star Game, saw Mays play for the Barons at the Polo Grounds. After the Giants signed Mays to a contract, Hubbell recalled that game at the Polo Grounds as “the day I saw the best goddam baseball player I have ever seen in my life.”

Mays joined the Giants in 1951 and after a shaky start won the National League’s Rookie of the Year award, hitting .274 with 20 home runs. That year, the Giants won the pennant in a memorable playoff game against the Brooklyn Dodgers in which Giants’ outfielder Bobby Thompson hit the game winning home run (Mays was on deck). Mays spent the next two years in the U.S. Army, and when asked about it later said simply, “You’ve got to serve your country, and that’s what I did.”

The next year, 1954, Mays led the Giants to another pennant and a World Series championship. He was the league’s Most Valuable Player (MVP), batting .345 (the league’s best) and hitting 41 home runs. Eleven years later — then playing in San Francisco — he won his second MVP award, hitting a league-leading 52 home runs, driving in 112 runs, and batting .317. Those were the only two MVP awards Mays won, but John Shea believes Mays should have received the award between eight to 11 times during his career.

Mays, like other African-American players in the 1950s and 1960s, suffered racial slights and discrimination, but he never became bitter, outspoken, or confrontational. Some civil rights leaders criticized Mays for this approach, but Shea notes that Mays “dealt with bigotry in his own way…. He fought discrimination on his terms…. He tried to break down prejudicial barriers by demonstrating character and leadership.” As his best biographer, James Hirsch, explains, Mays led by example, serving “as a role model who never drank or smoked, who avoided scandal, and who gave his time and money to children’s causes; as a player who excelled through discipline, preparation, and sacrifice; and as a man who brought Americans together through the force of his personality and his passion for the game.”

One of the keys to Mays’ character is the gratitude he has for those who made his life and career possible — family members, friends, and mentors who paved the way to his success: his father, Willie Howard Mays Sr.; his teammates in the Negro League; his first manager, Leo Durocher; his player–mentor Monte Irvin; and Jackie Robinson, who courageously broke the racial barrier for all future African-American baseball players.

Hirsch best captured Mays’ most important legacy. It is not the statistics, the home runs, or the Gold Gloves, he wrote. Instead it is “the pure joy that he brought to fans and the loving memories that have been passed to future generations so they might know the magic and beauty of the game.”