Writing in the Wall Street Journal on February 12, Max Raskin argued,

The bar for investigating political opponents should be high, especially when offenses are selectively enforced or derivative of the investigation. Many crimes — marijuana possession, jaywalking — are already selectively enforced. If prosecutors were to pursue only Democrats or only Republicans for such crimes, they would undermine the rule of law.

“Derivative of the investigation” refers to so-called “process crimes” — had there been no investigation, there would have been no crime. The Scooter Libby case from the last Bush administration was one example — no crime was ever uncovered in the investigation, but Libby was convicted for a few of his answers during the investigation.

A federal investigation is a daunting thing. When the resources of the entire federal republic are at the disposal of the prosecution, an individual faces ruin. Extended interrogation extends the possibility of answers that can be presented as criminally deceptive, adding exponentially to the danger of the one being investigated. The ghost of Stalin’s chief of the secret police, Lavrentiy Beria, lurks, chanting his mantra, “Show me the man and I’ll find you the crime.”

Of course, civil liberties are not the only legitimate concern of law and government. The country must be able to protect itself against corruption, dereliction, and treason. As ever, there is a need for a careful balance.

Take the most serious of the above-mentioned offenses: treason. The Founders had seen how treason had been used in the great impeachment trial of Charles I’s leading adviser, Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford. The House of Commons saw Strafford correctly as their dangerous enemy and sought his ruin through impeachment for treason. But their impeachment managers had no clear evidence of such a sin, and they fell to advancing a concept they called “cumulative treason.” Despite no one piece of evidence of a clear act of treason, Strafford should be convicted because the cumulative weight of all his actions had to be considered treasonable. The argument collapsed of its own weight, and the managers had to abandon the impeachment, eventually gaining Strafford’s head through a bill of attainder.

Seeking to blunt such murderous politics as constitutionally destructive, the Founders defined the crime of treason in the Constitution itself by setting an extraordinarily high bar for conviction: treason could only be for “levying war against the United States” or aiding its enemies, and it required testimony to an overt act by at least two witnesses or by the defendants own confession in open court only. It has served the original intention well: the only politician to be tried for treason, Aaron Burr, was acquitted.

Presidential impeachment also allowed bribery as a cause for removal from office. But American legal precedent has insisted on a high bar for this, as well, with the unanimous ruling in the McDonnell case that bribery cannot consist in merely setting up meetings or introductions for a campaign contributor. The court spoke with concern about intrusion of federal prosecutors and expansive criminalizing of political activities that the states are constitutionally free to allow.

In the concluding words of his opinion on behalf of all the justices, Chief Justice Roberts wrote,

There is no doubt that this case is distasteful; it may be worse than that. But our concern is not with tawdry tales.… It is instead with the broader legal implications of the Government’s boundless interpretation.

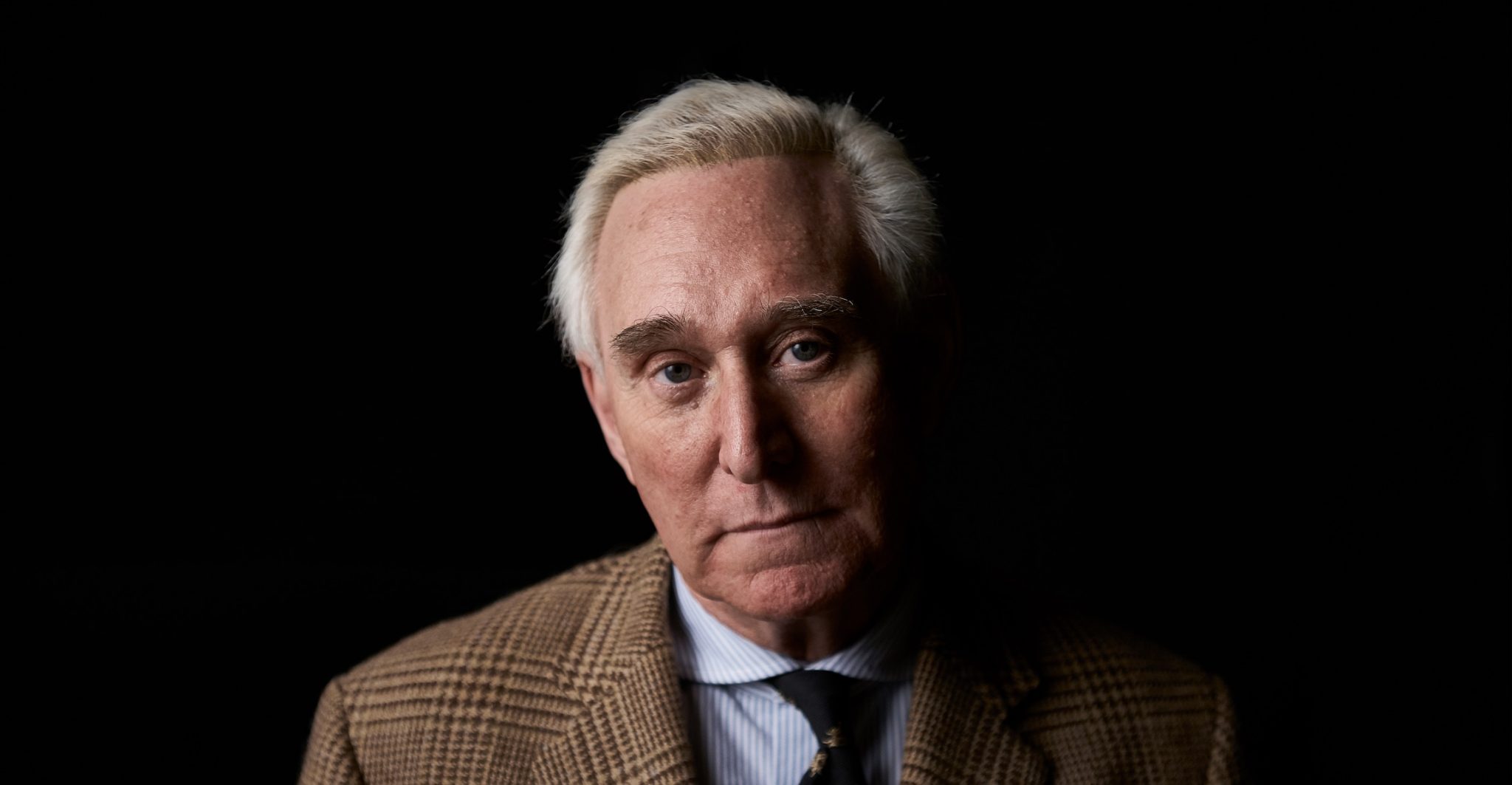

So, too, with Roger Stone. More than distasteful, his actions were illegal, and due process was followed. But Stone is not being offered a pardon or an exoneration — only making his sentence not something more than a drug dealer often gets. The affair smacks of revenge, of getting a sufficient thrill as a kind of comfort for letting the big one get away. That emotion should have no place in the DOJ, and the departure of the prosecutors of their own volition is a gift to be accepted with some satisfaction.

The actors of the investigatory state who have pursued their political aims through criminal processes have roiled this country unceasingly for more than three years. Their methods, while familiar to those of the Founders, are not consonant with what the Constitution was striving to achieve — a government that allowed its citizens the widest possible freedom in political debate and action and severely limited the use of the courts to gain political ends.

Alan Dershowitz summed it up: “I would like to see us pull back on using the criminal law against political figures who one disagrees with.” Yes, let’s pull back. Let’s banish the spirit of Lavrentiy Beria; the spirit of Madison, Hamilton, and Jay will continue to do just fine.