Paul isn’t dead. That John and George are does not mean we should rename their band Paul McCartney & The Beatles. One senses that some viewers of Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back Disney+ documentary, of which I am not one, come away thinking “I’ve got a feeling” Paul was, to borrow a phrase that Billy Preston applied to John, “Boss Beatle.”

“Get Back confirms that McCartney was not only the chief creative genius of the Beatles — it’s a dizzying miracle when he starts noodling around with the chords for ‘Let It Be’ and ‘The Long and Winding Road’ on consecutive days — but also its chief executive,” Kyle Smith writes @ National Review Online.

Get back, get way back from that television.

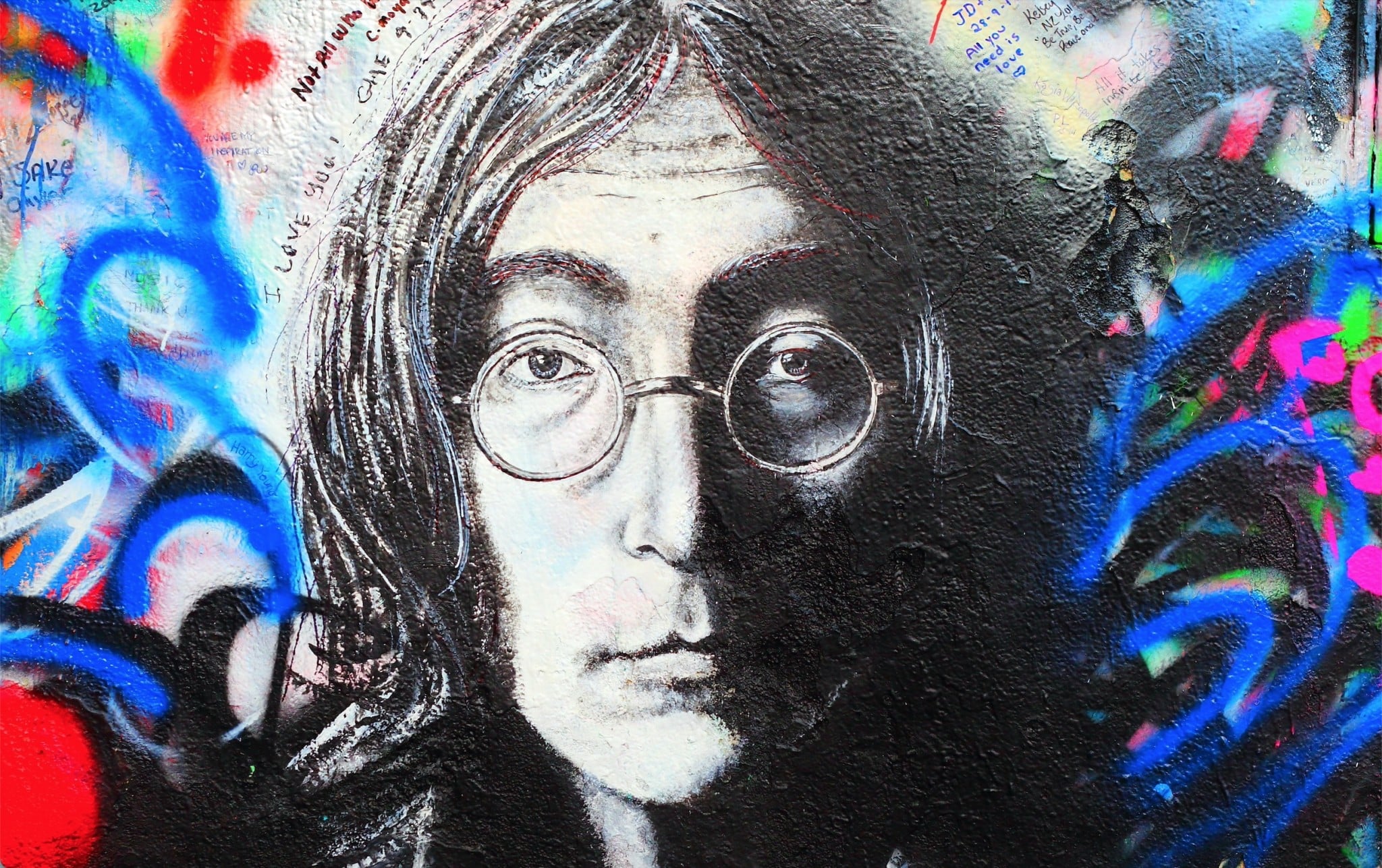

During peak Beatles, John stood out as the peak Beatle. Did Smith listen to Herman’s Hermits or Peter and Gordon rather than The Beatles during this period? The best singles, the best B-sides, and the best album tracks — “Nowhere Man,” “Norwegian Wood,” “In My Life,” “She Said She Said,” “Tomorrow Never Knows,” “Rain,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “A Day in the Life,” “All You Need Is Love” — from Rubber Soul through Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band all came to life primarily through the creative genius of John Lennon.

This film looks at a period during which John had checked out and Paul had become Alpha Beatle. On the band’s final two albums, Paul unquestionably dominated. John offers an occasional gem — “Across the Universe” and “Don’t Let Me Down” come to mind — but the Fab Four circa-1969 did increasingly look like a dress rehearsal for Paul’s solo career. To extrapolate Paul’s dominance in this moment upon the entirety of The Beatles misses something even if an eight-hour documentary seems to miss nothing.

“Get Back is so exhaustive and thorough in trying to present a fair picture of the sessions that it should put to rest any notion that McCartney was a tyrant who drove the others out of the band; the breakup was primarily caused by Lennon and McCartney’s dispute over whether the band’s manager should be Allen Klein, who handled the Rolling Stones,” Smith, who blames Lennon here, writes.

Come again?

McCartney’s dispute involved not just Lennon but George Harrison and Ringo Starr. Not for the last time did three guys outvote one guy in a band. The special circumstance here, unmentioned in Smith’s piece, revolved around McCartney’s choice for manager: Lee Eastman (ironically an altered last name that morphed from Epstein). If The Beatles really broke up over the choice of management, as Smith maintains, then the fault over the band’s dissolution falls squarely on the guy who wanted his father-in-law to run the group and not the guy who sided with his two other bandmates in thinking this a colossally bad idea.

Of course, so much else influenced the breakup. And, of course, John, Paul, George, and Ringo composed The Beatles. They all mattered. Give us both enough alcohol, and I can make a convincing case that Ringo ranks as the most important member. Sober assessments do not put John ahead of Paul or Paul ahead of John.

Chris Richards of the Washington Post seems on to something in arguing that our present’s penchant for rebooting another’s past means that The Beatles (or reboots of The Lion King on Broadway, The Equalizer on TV, and even b-pictures such as Nightmare Alley on the silver screen) smothers today’s creative output. But he loses readers in his admitted hot-takism that “the Beatles are overrated.” The fact that every decade or so the public goes Beatlemania over The Compleat Beatles or the Beatles Anthology, or that a Beatles greatest hits package released in the early years of this century ranked as the bestselling album of that decade (What music from the 1920s dominated the charts in the 1960s?) affirms Richards’s point about retromania as it undermines his point about their reputation surpassing their greatness.

Andy Meek most closely arrives at the truth in his piece at BGR.com.

“Decades later, Peter Jackson gets hold of the original footage,” Meek sums up of the conventional wisdom surrounding this documentary. “He restores it and re-assembles it into a new package — a three-episode, six-hour docuseries streaming now on Disney+. And, voila. Fans around the world feel like the story now has a better ending. That the bandmates weren’t at each other’s throats 24/7. That the breakup was sort of blown out of proportion. Because here, here is visual proof. Lindsay-Hogg must have gotten it wrong. Only, everybody is forgetting one thing. There’s still 50 hours of additional Beatles footage, people.”

Jackson, in this eight-hour epic, wants us to forget about a crucial 35 minutes: Let It Be.

Ian MacDonald in Revolution in the Head rightly calls the album “a fiasco” and describes the recording as “dispiriting sessions.” Unfortunately for Disney, 60 hours of footage does not exist for Revolver or Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. So, they work with what footage they possess, essentially remaking Michael Lindsey-Hogg’s Let It Be for the same reason The Beatles themselves actually issued a rebooted Let It Be a few years ago: the original disappointed.

The album’s failure —that word used here mostly in terms relative to its aspirations but also to the band’s catalog — most conspicuously announces itself in Phil Spector’s orchestration drowning “The Long and Winding Road” and “Across the Universe” with sappy strings (here, and not with Klein, Lennon erred terribly). A project predicated on a live sound ended up overproduced, or, in the case of “Dig It” and “Maggie Mae,” unfinished numbers better left unproduced. While few casual Beatles fans travel the full journey of Peter Jackson’s lengthy “Lord of the Ringos,” the ones who do undoubtedly come away with an impression of something monumental rather than a middling Beatles album containing a few gems.

Disney makes little girls imagine themselves princesses and little boys think not Everest but Space Mountain the peak worth conquering. Hollywood cannot convince that Let It Be marks a great moment in a great band’s history or that the end came more happily for The Beatles than it did for their fans. And this happy ending, perhaps desired by Ono and McCartney to rewrite their deserved or undeserved bad guy roles, strikes as entirely unnecessary.

The Beatles, a pop-culture force even greater than Disney, already gave fans a happy ending. It’s called Abbey Road. The band reconvened later in 1969 to reunite with George Martin to make their best album. It allows an eclipsed George to shine with two of his most brilliant tracks, “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun.” Ringo, for the only time, gives a drum solo on a Beatles record. Many listeners for the first time hear a synthesizer. The side-two medley, largely a creation of Paul, lyrically explains to bereaved Beatles fans, “Once there was a way to get back homeward/Once there was a way to get back home/Sleep pretty darling, do not cry/And I will sing a lullaby,” and sonically serves up the personalities of Paul, George, and John in sequential guitar solos.

The bassackwards release of the penultimate and final albums make this happy ending not as neat as a Disney production. But Beatles fans know they got it right at the end. And they know this not by watching documentaries but by listening to music.

Why not take Mother Mary’s advice and let it be?