Kangaroo-Squadron-American-Courage-Darkest/dp/0306903121">Kangaroo Squadron: American Courage in the Darkest Days of World War II

By Bruce Gamble

(Da Capo Press, 400 pages, $28)

It’s appropriate that I started writing this on Thanksgiving morning. We all have every reason to be thankful for the courageous Americans who stood up and did their duty during WWII, including the flyers military historian Bruce Gamble brings us in the very readable Kangaroo Squadron.

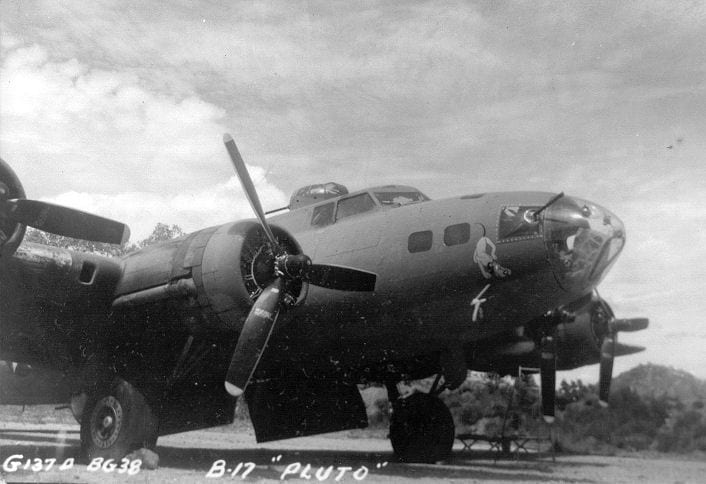

To clear things up, no, these guys didn’t fly kangaroos. They flew the sturdy and all around commendable B-17, one of America’s reliable war horses in WWII and a character in this book almost as much men who flew them. The squadron’s name comes from the fact that these American warriors were stationed mostly in Australia in the early days of WWII, when America and her allies had few troops, few assets, and little in the way of prospects in the South Pacific.

The dire situation came from the fact that America’s military in late 1941 and early 1942, just coming out of its post-Great War neglect, was way less than adequate to fight another world war. America would soon enlist and train the required warriors, and its industrial capacity would ramp up quickly to produce the necessary material. But early on things were grim, especially in the Pacific as allied leaders had made the strategic decision that the defeat of Nazi Germany was the first order of business.

The Pacific didn’t get much in 1941 and 1942. But it got the Kangaroo Squadron, the members of which performed admirably while having to deal not just with a well-equipped and battle-hardened Japanese air force and navy, but with primitive conditions, tropical diseases, bad food, bad water, terrible flying weather, little in the way of the parts and maintenance their planes needed, and in the case of crews downed in New Guinea, perhaps the most hostile-to-humans environment on the planet. Most of the men whose experiences Gamble chronicles, whether or not they ever battled the Japanese, had to battle with one or more of malaria, dengue fever, dysentery, typhus, hookworm, or various skin diseases we will not linger over.

Another complicating factor and a very real danger for flyers in the Pacific campaign was the sheer size of this huge ocean which covers a quarter of the planet’s surface. Navigation was a much more primitive art in those days. No global positioning systems to exactly pinpoint where an aircraft is in relation to where it’s going. Flyers had to rely on a navigator, hopefully well trained, with charts and an instrument to “shoot the stars” (if it wasn’t daytime or too cloudy). Crossing thousands of miles of ocean, the navigator’s position estimate couldn’t be verified until a landmark could be seen. And guess how many landmarks there are in thousands of square miles of ocean in which navigators hoped to find their way to the tiny islands that were their destinations. God had to be looking over those who made it.

Fuel consumption was a critical issue on long flights. Auxiliary fuel tanks were necessary on such long hops. But even with these, unexpected head winds or small errors in navigation that added miles to the trip could leave B-17s arriving at their destination on fumes. Or worse. So Pacific flying duty presented countless deadly hazards that could do flyers in as quickly as the Japanese enemy. Nothing in this job was safe.

Or comfortable. The rugged B-17 could take a considerable amount of battle damage and still return its crew to base safely. It could continue to fly on three, even two engines. But it had zero creature comforts. It was unpressurized. Above 10,000 feet crew members had to wear oxygen masks. But these systems were prone to breakdowns, which could prove fatal. At low altitudes condensation formed on the guns and in oxygen lines. At high altitudes, where temperature dropped well below zero, this condensation froze and could jam the guns and create problems for the oxygen systems.

Until flyers finally got the right kind of gear for high altitude flying, frost bite was a problem. (Imagine serving in some of the hottest climates on the planet and suffering from frostbite.) And of course the plane’s four 1,200 horsepower Wright “Cyclone” engines sounded like a real cyclone, and the noise never ended during bombing, reconnaissance, and patrol missions that could last 12 hours or more. When the .50-caliber machine guns had to come into play against Japanese fighters the sound was ear-splitting.

Once in the fight, this small group of American bombers could deliver little more than pin pricks to important Japanese targets like Rabaul. But their limited efforts and the strikes by planes from the carriers Lexington and Yorktown held the Japanese at bay long enough for American forces in the area to build up and to start taking the fight to the Japanese. Along the way, Australia was saved from invasion and capture, which was critical to the allies’ ultimate success in the Pacific. (Just imagine the American island-hopping campaign having to be conducted and supplied out of San Diego.)

Gamble is a historian and the author of six other books on the Pacific campaign in WWII. In Kangaroo Squadron he skillfully blends the stories and individual exploits of the men who represented America in the South Pacific during its most perilous time with developments in the Big Picture of the Pacific war until late 1942. The time covered includes the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor through the Battle of the Coral Sea, Midway, and the beginning of the Solomon Islands campaign in Guadalcanal. (Of course the squadron members Gamble chronicles, like most all soldiers and sailors in all wars, knew little of the war’s big picture, the frightening and arduous little picture before them being enough to occupy all their resources.)

The squadron also provided taxi service for General Douglas MacArthur, his staff, and his family, flying this group to Australia from Mindanao in the Philippines after the general had been on a long and perilous PT boat ride from Corregidor, soon to be in Japanese hands. Gamble’s complete narrative shows this trip was more complicated and less of a sure thing than most post-war documentaries have portrayed it.

Late in 1942 the members of the Kangaroo Squadron were rotated back to the States. Most returned home though, sadly, not all. Some had paid the ultimate price. There was a lot of war left and the Kangaroos had been in it for less than a year. But it was an exhausting year with very demanding flying schedules and just about every danger and difficulty that could be imagined. The squadron had acquitted itself admirably and was instrumental in the momentum of the war shifting to the allies. Most of the squadron spent the remainder of the war training other flyers who would contribute to the eventual successful conclusion of the war. Most went back into civilian life after the war, others chose a career in uniform, at least a couple of them making it to flag rank.

Gamble is a fine story-teller. His narrative in Kangaroo is fast-moving and full of vivid descriptions and moving detail of a group of American warriors that deserve to be remembered with gratitude. Anyone interested in WWII will find this book worth the time.