In November 1982, Richard Pipes, on loan from Harvard University to President Ronald Reagan’s National Security Council staff, was putting the finishing touches on what would become National Security Decision Directive 75 (NSDD-75), the strategic blueprint for winning the Cold War. In hindsight, NSDD-75 deserves to be treated the way historians have treated George Kennan’s “Long Telegram” (1946), his “X” article in Foreign Affairs (1947), and NSC-68 (1950), whose principal author was Paul Nitze. These four documents are the strategic bookends of America’s victory over the Soviet empire.

The Long Telegram, Kennan’s “X” article, and NSC-68 broke with the tradition of American foreign policy that reached back to President George Washington. Prior to the late 1940s, the United States remained geopolitically distant from the struggles for power in Eurasia, except for brief periods of time, such as during World War I, when it intervened to uphold the global balance of power. After World War I, American foreign policy swiftly returned to geopolitical distance (or what some commentators have called “offshore balancing”), even as storm clouds gathered in the 1930s.

When World War II ended, there was a general sentiment in the country to “bring the boys home” and let the European and Asian powers or the new United Nations keep the peace. The Soviet Union throughout the latter part of the war was depicted in the United States as our gallant wartime ally. Kennan knew better. He had served in our Moscow embassy in the 1930s and, later, in the mid-1940s. Kennan understood that the Soviet Union was an expansionist power motivated by Marxist-Leninist ideology and Russian history.

In one of those fortuitous moments in history, after the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin delivered a speech at the Bolshoi Theater on Feb. 9, 1946, the State Department, with Ambassador W. Averell Harriman absent from Moscow, asked Kennan, who was then chargé d’affairs at the embassy, to assess Stalin’s remarks. Kennan was told to “express your opinions and send them in.” Kennan wrote more than 5,000 words in what became known as the Long Telegram. It sounded the alarm about Soviet intentions in the postwar world. Harriman in Washington read it with interest and shared it with Navy Secretary James Forrestal, who showed it to President Harry Truman and his key advisers.

A year later, then director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, Kennan, using the pseudonym “X,” wrote the aforementioned article in Foreign Affairs titled “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” in which he expanded on his analysis in the Long Telegram and recommended a policy of “firm and vigilant containment” of the Soviet Union. This meant breaking with offshore balancing and forcibly resisting Soviet encroachments in Europe and Asia. Containment became the strategic foundation of America’s postwar foreign policy. And three years later, after China fell to the communists and aligned with Moscow, Paul Nitze, who succeeded Kennan as head of the Policy Planning Staff, authored the classified version of containment known as NSC-68, which called for strengthening our alliances and beginning a massive military buildup to prevent Soviet domination of Eurasia.

Containment had its critics, including Walter Lippmann, who believed it overcommitted the United States, and James Burnham, who argued that it was too defensive and who called for liberating the territory under Soviet control. But containment survived as America’s strategic doctrine until the presidency of Ronald Reagan. And that is where Richard Pipes and NSDD-75 came into play.

Reagan had been one of the fiercest critics of the softened version of containment known as détente, especially as practiced by the Carter administration in the late 1970s. Reagan believed that the Soviet empire was vulnerable because the regimes in Eastern Europe propped up by Moscow never achieved political legitimacy and because the Marxist-socialist economic system was fragile. Pipes shared those beliefs.

Paul Kengor wrote that NSDD-75 “was probably the most important document in Cold War strategy by the Reagan administration, and certainly the most significant and sweeping directive in terms of institutionalizing the Reagan intent and grand strategy.”

In the mid-to late 1970s, Pipes served on the Committee on the Present Danger, a bipartisan group that sounded the alarm about growing Soviet military capabilities and that pronounced détente as obsolescent. Nitze also served on the committee, and Reagan was on its board of directors. After the 1980 election, Reagan’s incoming National Security Adviser Richard Allen asked Pipes to serve on the new administration’s National Security Council (NSC) staff. Pipes in his memoirs described the members of the staff recruited by Allen as “a team of experts untainted by the conventional wisdom on détente and arms control as centerpieces of U.S. foreign policy.”

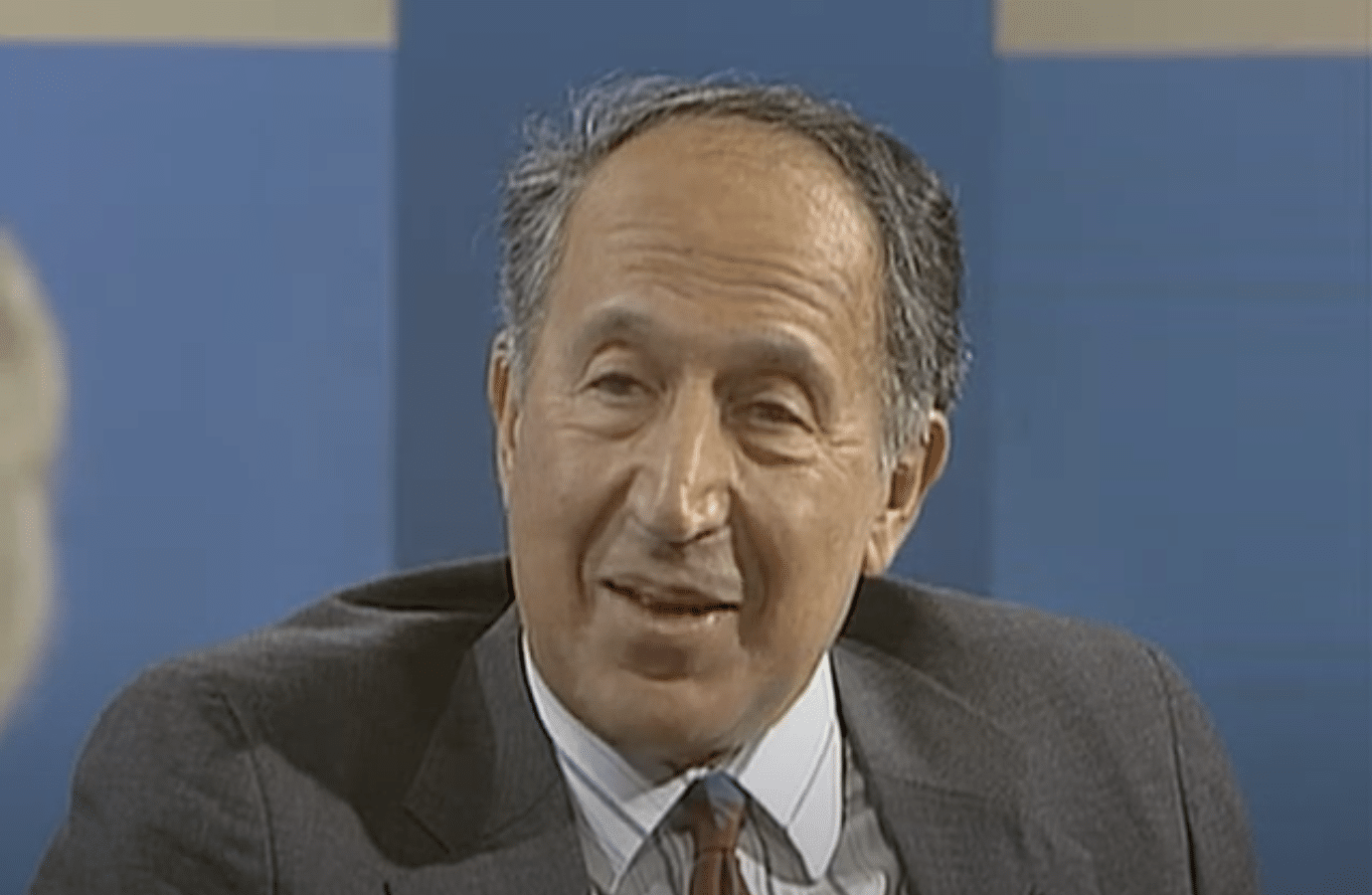

Pipes, a historian of Russia, was subsequently appointed head of the East European and Soviet desk at the NSC. He took leave from teaching at Harvard and committed to working in the administration for two years.

Pipes recalled reading intelligence reports about the structural weakness of the Soviet economy and the waning legitimacy of the Communist Party. Reagan instinctively agreed with this intelligence, even though many in the State Department and the White House urged Reagan to disregard his instincts about Soviet vulnerabilities. Pipes in his memoirs attributed Reagan’s approach to his keen “political judgment.” But Reagan had been fighting communists since his days in Hollywood as head of the Screen Actors Guild. He had read widely on the history of communism and had been influenced by the writings of Burnham and Whittaker Chambers. And he would also be influenced by the writings of Pipes, especially NSDD-75.

During his two-year stint on the NSC staff, Pipes worked on what he called “a general policy statement of the Reagan administration’s policy toward the Soviet Union,” which became NSDD-75. Like Kennan’s Long Telegram and “X” article and Nitze’s NSC-68, Pipes’ NSDD-75 urged the United States to break with existing policy — in this instance, containment.

Even before the final draft of NSDD-75 emerged, Pipes had written a paper for Reagan urging him to “promote the reformist tendencies in the USSR by a double-pronged strategy: encouraging proreform forces inside the USSR and raising for the Soviet Union the costs of its imperialism.” This paper served as the theoretical basis of Reagan’s famous London speech in June 1982, in which he publicly envisioned the collapse of the Soviet Union. Pipes and Reagan believed, in Pipes’ words, that the “policy of containment … had long been overtaken by events.”

Pipes wrote the final draft of NSDD-75 in November 1982. The State Department opposed its confrontational approach and wanted to modify it, but Reagan’s National Security Adviser William P. Clark liked Pipes’ draft. Pipes identified in his memoirs the “key paragraph of NSDD-75 which established as a goal of U.S. foreign policy” the following:

To promote, within the narrow limits available to us, the process of change in the Soviet Union toward a more pluralistic political and economic system in which the power of the privileged elite is gradually reduced. The U.S. recognizes that Soviet aggressiveness has deep roots in the internal system, and that relations with the USSR should therefore take into account whether or not they help to strengthen the system and its capacity to engage in aggression.

But it was the preceding paragraph of NSDD-75 that stated that the “primary focus of U.S. policy toward the USSR” was to “contain and over time reverse Soviet expansionism by competing effectively on a sustained basis with the Soviet Union in all international arenas.” This included efforts “to loosen Moscow’s hold” on Eastern Europe. This was the heart of Reagan’s policy, which, over time, undermined the Soviet empire by resisting Soviet geopolitical offensives, sustaining a U.S. military buildup to reestablish the military balance, supporting nationalism within the Warsaw Pact countries, and straining the Soviet economy to its breaking point. Pipes’ final version of the classified NSDD-75 was formally issued on Jan. 17, 1983.

As Steven Hayward has written, “with NSDD 75, the Reagan Doctrine was born.”

In his important book on Reagan and the fall of communism, Paul Kengor wrote that NSDD-75 “was probably the most important document in Cold War strategy by the Reagan administration, and certainly the most significant and sweeping directive in terms of institutionalizing the Reagan intent and grand strategy.”

And Kengor noted that Pipes’ strategy document “turn[ed] on its head the doctrine of containment that had formed the cornerstone of American foreign policy since George Kennan sent his famous ‘Long Telegram’ from Moscow in February 1946.” Peter Schweizer characterized NSDD-75 as the founding document of what he called “Reagan’s war” against the Soviet Union.

Richard Pipes died in 2018 at the age of 94. There are no biographies of Pipes, as there are of Kennan and Nitze, but there should be. Forty years after he finalized NSDD-75, it should be acknowledged that his contribution to America’s Cold War victory was as important — perhaps even more important — than Kennan’s or Nitze’s. In every sense, he was a hero of the Cold War.