When the White House invited my elementary school boys choir to sing at its 2008 Christmas party, I felt deeply embarrassed. This was George W. Bush’s last Christmas as president, and even I knew he deserved better than a chorus of 50 half-trained fifth graders singing his swan song.

But a call from the president is not to be ignored. So our director selected a batch of Christmas carols, and we all showed up to the White House decked out in blue blazers and baggy khakis. Not long after, Secret Service plopped us on a staircase, where we sang for about an hour — poorly. Bush happened to walk by our perch during “In the Bleak Midwinter” and stopped to listen. It must have been an agony, but he stuck it out for the whole song. At the end, he thanked us for coming. Then he shook our hands.

For a fifth grader, the president’s goodwill in that moment seemed tremendous. For Bush, it was part of the job. Even with less than a month left in office, he served us as a gracious host. Service an oft-remarked-upon virtue in the Bush family — perhaps overstated in many of the eulogies after H. W.’s death — but the praise is more than hagiography. George W. Bush is still a servant, even after his presidency. This is no more apparent than in his portraits of veterans, on view in “Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors” at the Kennedy Center’s REACH through November 15.

Much like myself in fifth grade, Bush is not a natural artist. He only picked up painting in 2012, as a pastime, after learning that Winston Churchill painted landscapes to ease his mind. But where Churchill used his brush to escape from war, Bush soon focused on its effects. In 2015, with the encouragement of his instructor Sedrick Huckaby, Bush began painting disabled veterans whom he had met during the bike rides and golf outings organized through his post-presidential charity the Bush Institute.

Bush selected 98 soldiers who had suffered either physical or mental wounds in combat. Before beginning work, he interviewed them and studied their biographies. Although he worked from photographs, Bush attempted to overcome the flatness inherent to that medium by presenting what he had learned through conversation in heavy impasto and a palette limited to the primary colors. Bush also narrowed his field of vision exclusively to the faces of his subjects. The result is a series of often gut-wrenching psychological studies.

“As I painted them, I thought about their backgrounds, their time in the military, and the issues they dealt with as a result of combat — many from visible injuries, others from invisible wounds such as post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury,” Bush wrote in the book version of the portraits.

Many of his subjects were surprised by the results. The paintings are not good in any artistic sense, but they are perceptive. Leslie Zimmerman, a former medic who served in Iraq, told the Daily Mail in 2017 that Bush had somehow translated her PTSD to the canvas.

“He definitely picked up on the sadness in my eyes,” she said. “I feel like he looked at how I was feeling, because I was talking about something so personal and serious during that interview. And I can kind of see the sadness on my face in the portrait.”

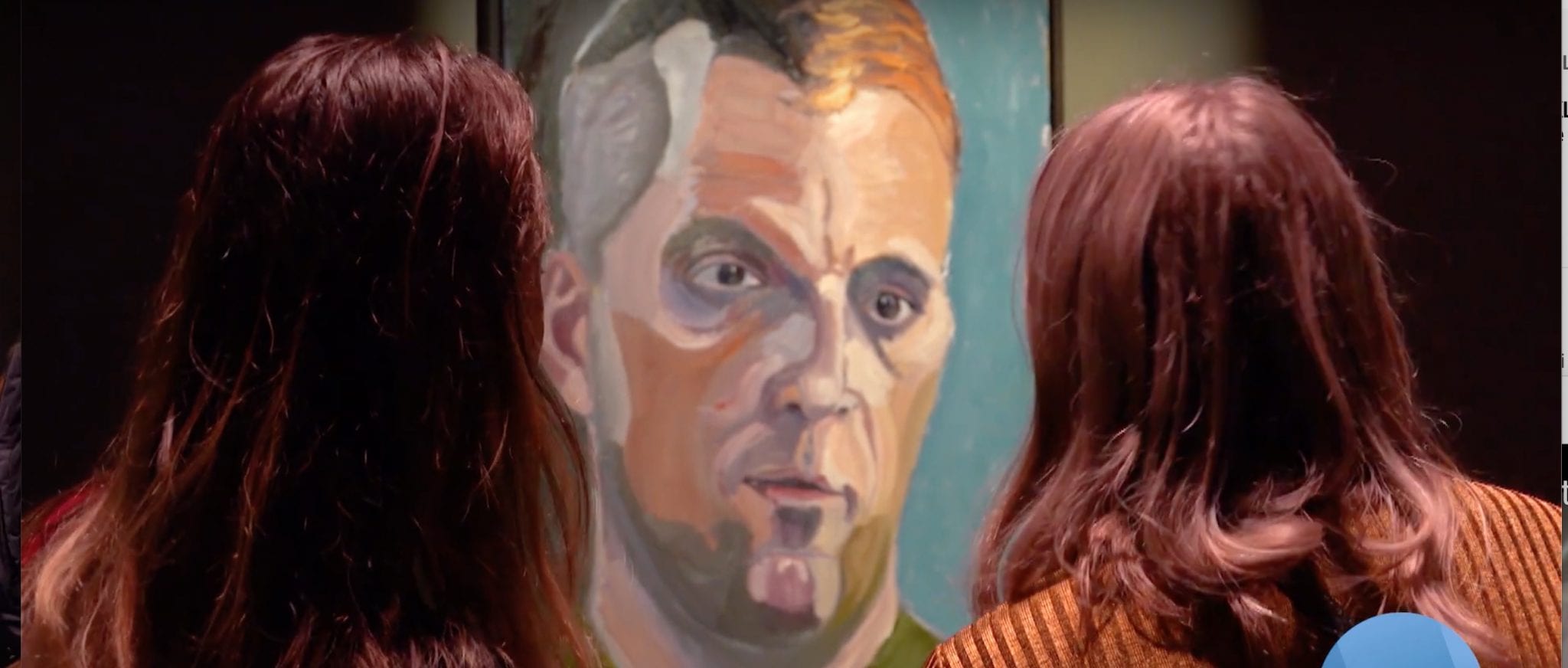

That sadness — the so-called thousand-yard stare — surfaces in so many of the portraits at the Kennedy Center. The whole exhibition seems to be organized around it: visitors must walk through a darkened gallery, draped with black curtains, where only the faces of the wounded are illuminated. These are presented without explanation, and none are signed. When I visited (admittedly early on a weekday), it felt as if a reverential silence had descended on the room.

Of course, it’s not all somber. There are several smiling group portraits and a few upbeat scenes of paraplegic veterans playing golf. But it’s portraits such as the one of Chris Goehner, an Iraq veteran diagnosed with PTSD due to survivor’s guilt, that anchor the series.

Bush portrays Goehner in a melancholy mixture of reds and browns against a fiery orange background. Goehner stares grimly out from the canvas toward some far-away no-place. This is the face of a man who constantly thinks about death and contemplated suicide — and yet has refused to succumb.

The portrait is as revealing of the painter as it is of the one painted. Only someone who has seriously contemplated death could have created it. And Bush has quite a lot of death to consider: the worst terrorist attack on American soil, followed by two long and ill-considered wars. That he can produce such vivid depictions of suffering suggests the former president is coping with his own wounds.

And at the exhibition’s end, the view from the REACH invites more contemplation of death, not just in the Middle East, but in every American war. Thousands of soldiers lie buried in Arlington National Cemetery just across the Potomac River — demanding our silence and respect.