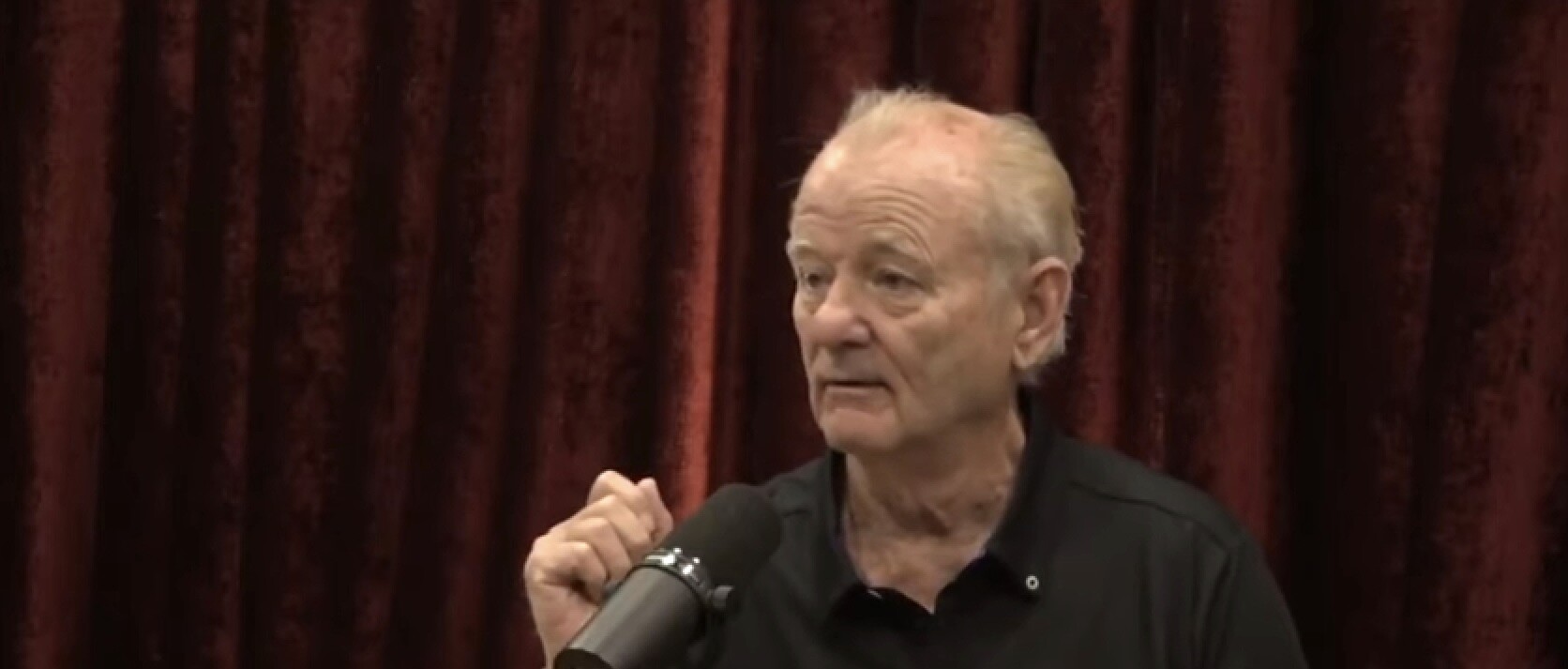

When Bill Murray questioned author Bob Woodward’s veracity during his recent interview on the Joe Rogan Experience, he was right on the money — particularly with regard to Woodward’s reporting on President Nixon.

Let’s look at the record that has emerged since Nixon resigned in 1974. (RELATED: The Conspiratorial Beginning of the End of Nixon’s Presidency)

First, there are interesting details about “Deep Throat,” Woodward’s inside source on Watergate developments, whose identity he carefully protected until it was revealed in 2003. He turned out to be Mark Felt, the former deputy FBI director who was bitter about being passed over as J. Edgar Hoover’s successor.

But for the intervening three decades, Woodward allowed — even encouraged — the belief that Deep Throat had been a member of Nixon’s own White House staff, so disgruntled with its criminality that he leaked details to Woodward. His deliberate obfuscations cast dispersions on many innocent members of Nixon’s staff. It also raises questions as to how much else of Woodward’s Watergate reporting was really accurate. (RELATED; Reevaluating the Saturday Night Massacre)

The movie version of All the President’s Men (1976) contains at least three overt indications that Deep Throat is a member of Nixon’s White House staff:

- In a scene shot on the steps of the Library of Congress, Bernstein (played by Dustin Hoffman) is bemoaning their lack of leads. Woodward (played by Robert Redford) says, “I have a friend at the White House,” and they are quickly off and running once more.

- Woodward phones Deep Throat at his office — and it’s from a phone booth directly across Pennsylvania Avenue from the Old Executive Office Building, which is part of the White House compound. Woodward is shown to be looking up at the Old EOB as he’s speaking to his source.

- In an eerie nighttime shot of his leaving work to meet with Woodward, Deep Throat (played by Hal Holbrook) is shown driving out of the White House Northwest Gate.

Further, there is the legitimate question of whether merely printing what an FBI source improperly leaks about an ongoing investigation is sufficient grounds to be considered the greatest investigative reporter of all time. Indeed, Angelo Lano, the lead FBI agent during Watergate’s entire unfolding, told a National Archives archivist in 2007 that Woodward’s reporting was of no help whatsoever since he was merely reporting what the FBI already knew.

Second, there are the wrongful denials about Woodward and Bernstein having interviewed Watergate grand jurors in 1973 — a criminal offense. One juror complained to prosecutors, and Democrat uber lawyer Edward Bennett Williams was dispatched to meet secretly with his dear friend, Judge John Sirica, to deny the accusation. (RELATED: The 18½ Minute Gap in Watergate Recording)

Years later, in 2012, a biographer of Washington Post Executive Editor Ben Bradlee discovered in his attic seven pages of typed notes of a grand juror interview. Her disclosures had been falsely attributed to a Nixon re-election campaign secretary in their book. Bernstein admitted the interview and the deception but justified it on the importance of the overall story. Woodward, for his part, threatened to ruin the biographer if he ever made the truth of that interview public.

Third, there is the inexplicable absence of investigation of secret meetings Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski had with Judge Sirica and House Judiciary staff. Jaworski had resigned in October 1974, at the beginning of the Watergate cover-up trial, and returned to his native Texas. He gave his first interview after leaving to Woodward on Dec. 5. Woodward’s typed notes from that interview were given to the University of Texas at Austin and first opened to the public on Feb. 4, 2007. The second sentence of the top page contains the following quote: “Says there were a lot of one-on-one conversations that nobody knows about but him and the other party.”

One can only wonder just who Jaworski might have been referring to, but the obvious candidate would have been Judge Sirica, with whom Jaworski had been meeting in secret on a regular basis. Documented proof of those highly improper conversations first surfaced in 2013 but could have been known some forty years before — with the attendant dismissal of prosecutors and judges alike — had Woodward bothered to follow up on Jaworski’s startling comment.

In the second paragraph of those same interview notes, Jaworski details how his prosecutors met secretly with House Judiciary staff to assist them in their impeachment efforts. Again, this was a revelation most deserving of Woodward’s follow-up, but it never came. Perhaps because it would have ruined the media’s false narrative of Watergate.

For all his sterling reputation, disclosures coming over the past 50 years show Woodward to be less of an investigative journalist than the public has been led to believe.

* * *

Geoff Shepard came to Washington in 1969 as a White House fellow after graduating from Harvard Law School. He served on President Richard Nixon’s White House staff for five years, including a year as deputy counsel on the President’s Watergate defense team. He has written three books, produced a stage play, and released a documentary regarding the internal prosecutorial documents he’s uncovered, many of which are posted on his website, www.shepardonwatergate.com.

READ MORE from Geoff Shepard:

The Conspiratorial Beginning of the End of Nixon’s Presidency