I decided to skip a performance by my favorite group at the very ballpark where I worked to pay for tickets to see them for the first time 30 years ago. Blame concert inflation, which, like ballooning costs for medical care and college tuition, ranks among the sharpest rises in price in recent decades.

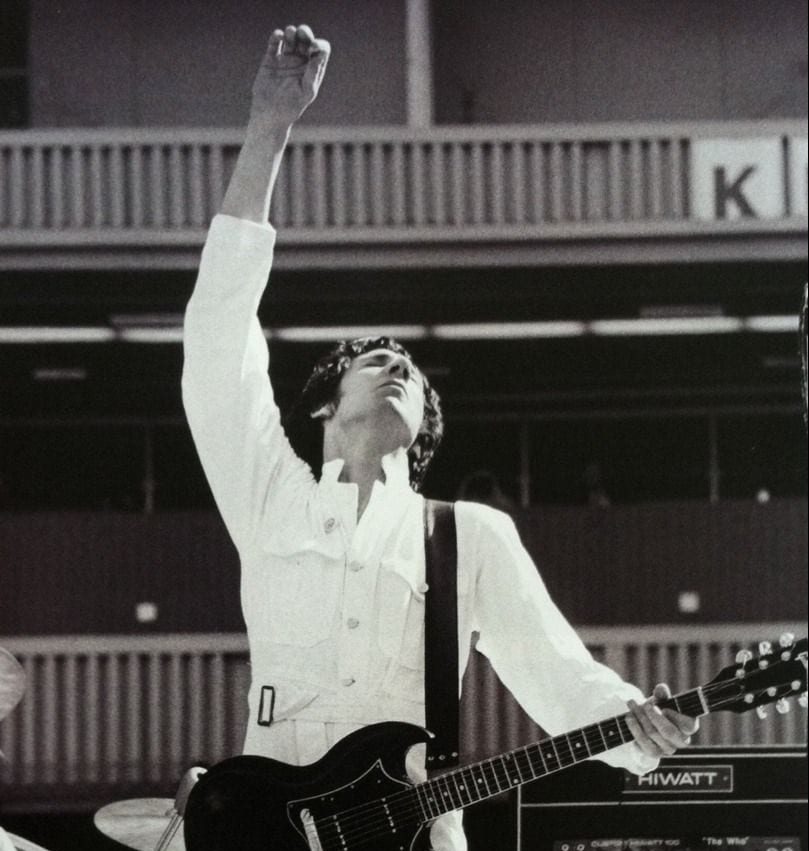

The cheapest ticket available for The Who at Fenway Park this September in my search cost $66.85, which included a $17 processing fee and, inexplicably, a second $4.85 processing fee. In 1989, when I saw The Who for the first time along with three friends, tickets cost $23.50. Getting a bead on processing fees, I charged my three companions a $6.50 “tax” to make my own ticket more or less free. Months later, one friend, really wanting to see The Rolling Stones, apparently asked himself, “What would Keef do?,” and proceeded to convincingly explain to his younger, sweeter girlfriend that if she did not come up with $60 (my processing fees rising sharply with demand by this point) then some hoods from a nearby city would murder him. For a U2 concert, I rented a U-Haul truck, stuffed a dozen or so concertgoers, a couch, and barbecue grill in the back, and proceeded to Sullivan Stadium satisfied in avoiding payment for an extra parking space.

This article is from the American Spectator print magazine. Click here for online access!

Occasionally scalping tickets to friends for Tom Petty, Guns N’ Roses, and other popular acts of the day provided a free concert ticket or supplemental cash at best and at worst resulted in a loss instead of profits — as occurred at the U2 event, a bath made more temperate by buying tickets below cost from fans desperate to unload extras on their way into the stadium — my aggressive, uncouth methods involved offering salt to quizzical faces seeking mere cost “because you’re going to eat that ticket,” only to sell them at face value moments later to others just as desperate to gain admittance.

Atop the risk of capital, scalping in high school often involved organizing transportation, a task made more difficult by a lack of a driver’s license, and obtaining alcohol, which proved difficult, albeit less so, as a result of similar legal nuisances. For one show, underage me boldly took a three-quarters-gone beer to the concession stand claiming contamination from overbleached taps. “Drink it yourself,” I implored only for the vendor to decline, as expected, and provide a fresh cup — a process repeated at seven more stands throughout the arena. This seemed just at the time given the exorbitant price of beer, the emptiness of our pockets, and unfair cultural hangups about teenagers drinking. And undercharging oneself for beer did not strike as such a moral leap from overcharging friends for tickets.

Like all middlemen, scalpers, accurately stereotyped as scally-capped gentleman dressed in track suits, became demonized. Performers blamed them for gobbling up seats and driving up prices. Ultimately, instead of beating the scalpers, the ticket conglomerates and acts became the scalpers.

When The Beatles played Shea Stadium in 1965, they charged $5. The average concert ticket price skyrocketed to five times that amount by 1996, and, according to Pollstar, to $91.86 this year. With price maximization per seat rather than a sellout the goal, the system eventually marginalized scalpers — yet another (somewhat) honest profession made obsolete by corporate greed.

The exorbitant prices make rock music, heretofore egalitarian on both sides of the stage, an enthusiasm indulged by the affluent or the fanatical. This, along with “artists” — the very word conveying a snobbishness — increasingly demanding passive listening instead of cathartic participation from audiences, helped exile the rock genre from top billing to an also-ran behind pop, country, and rap. “Awopbopaloobop alopbamboom” does not lend itself to seated, silent audiences. But shoegazing bands presenting themselves as “artists” often want just that.

In my youth, rock ruled youth culture. In the intervening years, video games, social media, superhero movies, and much else knocked it from its high perch. Music, which back then often dictated one’s social circle, matters less; rock music matters much less. Surely $92 tickets do not help by pricing out young people from that genre’s central, live experience whose energy exudes youth. Now, with Roger Waters, Bruce Springsteen, The Rolling Stones, and other senior citizens dominating the rock concert circuit, it seems more about recapturing, if for a night, youth.

As it turns out, I did just that after a friend — one who attended that first Who concert with me — offered a ticket for The Who at Fenway Park priced right at free. The Who, perhaps wisely, didn’t sing the words “hope I die before I get old” on this stop on their “Moving On!” tour. Rock music also got old and perhaps died sometime before that aging. But, on occasion, for just $66.85, one can, if for a few hours, witness a resurrection.

This article was originally published in The American Spectator’s fall 2019 print magazine. Click here for online access!