Few Christmas films merit a yearly watch.

The ones that do are mostly children’s cartoons: How the Grinch Stole Christmas, A Charlie Brown Christmas, Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol — network broadcasts played and replayed until they became unquestioned tradition.

There aren’t so many classic Christmas films for adults. It’s a Wonderful Life, maybe. My parents after a few drinks say Die Hard. Every few years someone suggests The Muppet Christmas Carol. Almost: Michael Caine scowls convincingly as Scrooge, but anything starring Miss Piggy belongs with the kids’ cartoons.

My pick is Fanny and Alexander, the Swedish Christmas epic. It requires a strong stomach. The full television version is nearly five and half hours long, and its director, Ingmar Bergman, spares little of that time for levity. Death, judgment, Heaven and Hell: that’s his gloomy milieu, no matter the season.

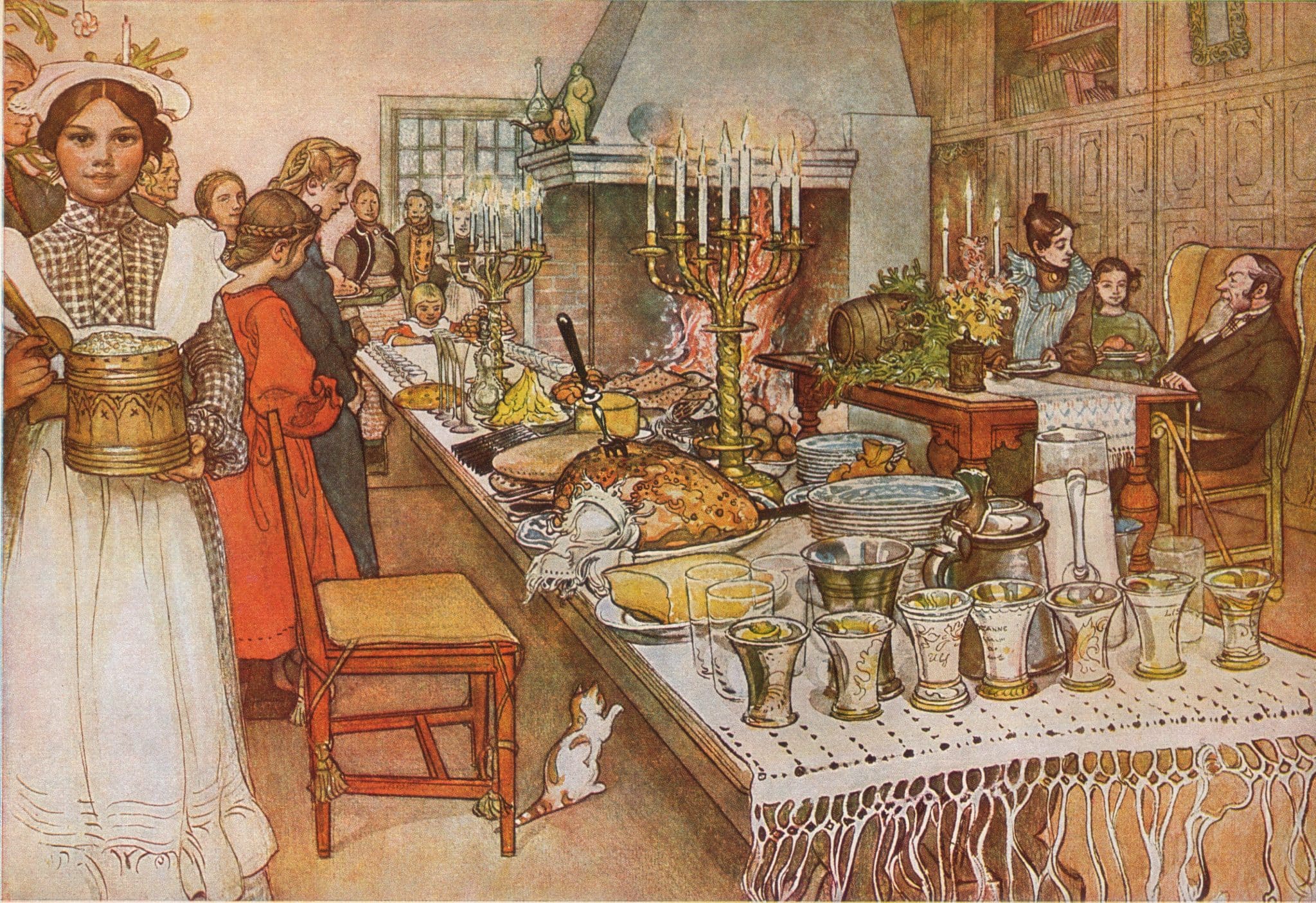

Bergman modeled the film’s main character, Alexander Ekdahl, on his own childhood self — impious, mischievous, and constantly pursued by evil spirits. In the film’s opening act, a lush Christmas party, Alexander sees Death grinning at him from behind a bush. The boy pays no mind; he’s the son of a well-off theater owner and one of the youngest members of a boisterous family. He sees costumed people all the time.

But soon, all manner of horrors visit him and his sister, Fanny. Their father dies, and their mother remarries. Their stepfather, a wicked Lutheran bishop, beats Alexander. There is no refuge. Pursed-lipped maids lock him in an attic where spectral children vomit in his mouth. As the severity of the physical torture increases, so too does the intensity of Alexander’s spiritual tests.

These trials culminate in a confrontation with a demonic apparition.

“You can’t escape me,” it says as it shoves Alexander to the ground.

Whether Alexander can is an open question. All demons do is lie, after all. And everything Bergman shows us afterward seems to indicate that Alexander at least has a chance at escape. In the film’s final scene, set almost a full year after its first, the boy curls up in his grandmother’s bed while she reads him to sleep. Christmas is just around the corner. Time to begin again.

It occurred to me after the first time I saw the film that the best Christmas art anticipates death. References to the Second Coming crop up in just about every popular Christmas hymn. Christ’s crucifixion features in many painted Nativity scenes. Look closely — there’s usually a skull nestled in nearby the ox and ass. Memento mori. Christmas is celebrated because the feast is Christ’s first pit stop on the road to Calvary.

Poets love to riff on this fact. “I had seen birth and death,/ But had thought they were different; this Birth was/ hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death,” writes T. S. Eliot in “The Journey of the Magi.” And W. B. Yeats, in my favorite Christmas poem, “The Magi,” does Eliot one better, describing the wise men on Good Friday with “their eyes still fixed, hoping to find once more,/ Being by Calvary’s turbulence unsatisfied,/ The uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.”

Bergman is on to something similar in Fanny and Alexander. In an early scene, Alexander’s family joins hands and runs around the family’s house singing a traditional Swedish Christmas song. It’s a beautifully shot sequence, all warm reds and golds. It’s probably the happiest we see anyone in the whole film.

“Christmas will last until it’s Easter,” the Ekdahls sings, before immediately adding, “No, that’s not true of course. That’s not true of course. For in between comes Lent and fasting.”

The rest of Fanny and Alexander is a sort of Lent. And, as with all things Bergman, Lent never ends — not until death at least. But for him each successive Christmas is a reminder that there’s at least a chance that it will end.

Maybe it’s better to stick with the cartoons.