On Monday night, I received a voicemail from Jack Anderson informing me that he had “resigned as defender of the bond in the diocese of Wilmington, effective immediately.” He added that he “wants nothing more to do with the Roman Catholic Church.” On Tuesday, I spoke with Anderson, asking him if he had been laicized after he left the priesthood in the diocese of Scranton. “That’s none of your business,” he said. But later in the conversation he indirectly revealed that he remains unlaicized, saying that at his advanced age he had no desire to “pursue laicization.”

To repeat what I wrote last Sunday, Anderson sat on a Catholic tribunal for over 20 years despite leaving the priesthood, entering a “gay marriage,” rejecting Catholicism in favor of Episcopalianism, and publicly opposing the Church’s teaching on marriage. I called up Robert Krebs, the spokesman for Wilmington Bishop Francis Malooly, to explain Anderson’s long presence on the tribunal. Krebs implausibly asserted that Malooly only learned of the scandalous “aspects” of Anderson’s life from my article on Sunday and the ensuing coverage. Asked if Malooly would have fired Anderson had he not tendered his resignation, Krebs said that he “refused to speculate.”

Eric Deabill, the spokesman for Bishop Joseph Bambera, didn’t return my calls. I wanted to ask why Bambera has not sought Anderson’s laicization. After all, Anderson, in his unlaicized state, remains not only a priest under Bambera’s authority but also a legal liability to the Church. Even the lax Pope Francis has said that men who leave the priesthood must be laicized, lest their misbehavior pose a liability to the Church. Why would Bambera, who normally does insist that ex-priests be laicized, take a risk in Anderson’s case? Don’t the unusually scandalous circumstances of Anderson’s status cry out for laicization?

“It is ironic,” says a Church observer. “Bambera gets conservatives who leave the priesthood immediately laicized. But he lets a gay married man in an openly heretical state remain unlaicized and working on a Catholic tribunal? That’s absurd and totally irresponsible. He is willing to risk the good of the Church for an old buddy of his from the seminary.”

Bambera, of course, has avoided any comment on the matter. But it is impossible for him to claim ignorance of Anderson’s work on the tribunal. For one thing, Bambera has long told Scranton-ordained priests that they have an obligation to inform him if they do canonical work outside of Scranton. As a canon lawyer himself, Bambera would also know all the players in the small world of tribunal work on the East Coast, not to mention the fact that he has a canonical duty to know the doings and whereabouts of non-laicized Scranton priests. Bambera’s vicar of priests and judicial vicar would have also known about Anderson’s work.

Why Anderson received such special treatment is puzzling. Does he have dirt on Scranton and Wilmington churchmen? He emphatically rejected that suggestion in our conversation. But he very casually acknowledged that his status did not square with the canonical requirement that the defender of the bond be an orthodox, practicing Catholic. “Apparently, it violated that [canon],” he said.

Another question that arises in the wake of this scandal is: Are all the annulments to which Anderson contributed valid? I asked a canon lawyer: “I don’t know the answer to that question,” he said. “That is an interesting issue.” To put it in secular terms, if it came out that a judge or prosecutor, say, had committed disbarrable deeds, wouldn’t the defendant call for a new trial? Wouldn’t the verdicts be tainted?

It was clear from our conversation that Jack Anderson favored easy annulments. He said that he conceived of his work as an act of mercy towards those who wished to “return to Communion,” an odd imperative since he himself has broken communion with the Church.

Still, Anderson acknowledged that he felt better after quitting the tribunal, calling it a moment of “integrity” wherein he has finally closed the breach between his work and his lifestyle. He even agreed with me that the modern Catholic Church is in a state of open hypocrisy as it teaches one thing officially and then does another. But he seemed oblivious to his own contribution to that hypocrisy. For example, he saw nothing strange in the fact that his work for the Wilmington tribunal began under its then–judicial vicar, Ted Olson, to whom he is now married in the eyes of the state of Delaware. And he couldn’t understand the “relevance” of my questions about Bambera not seeking his laicization.

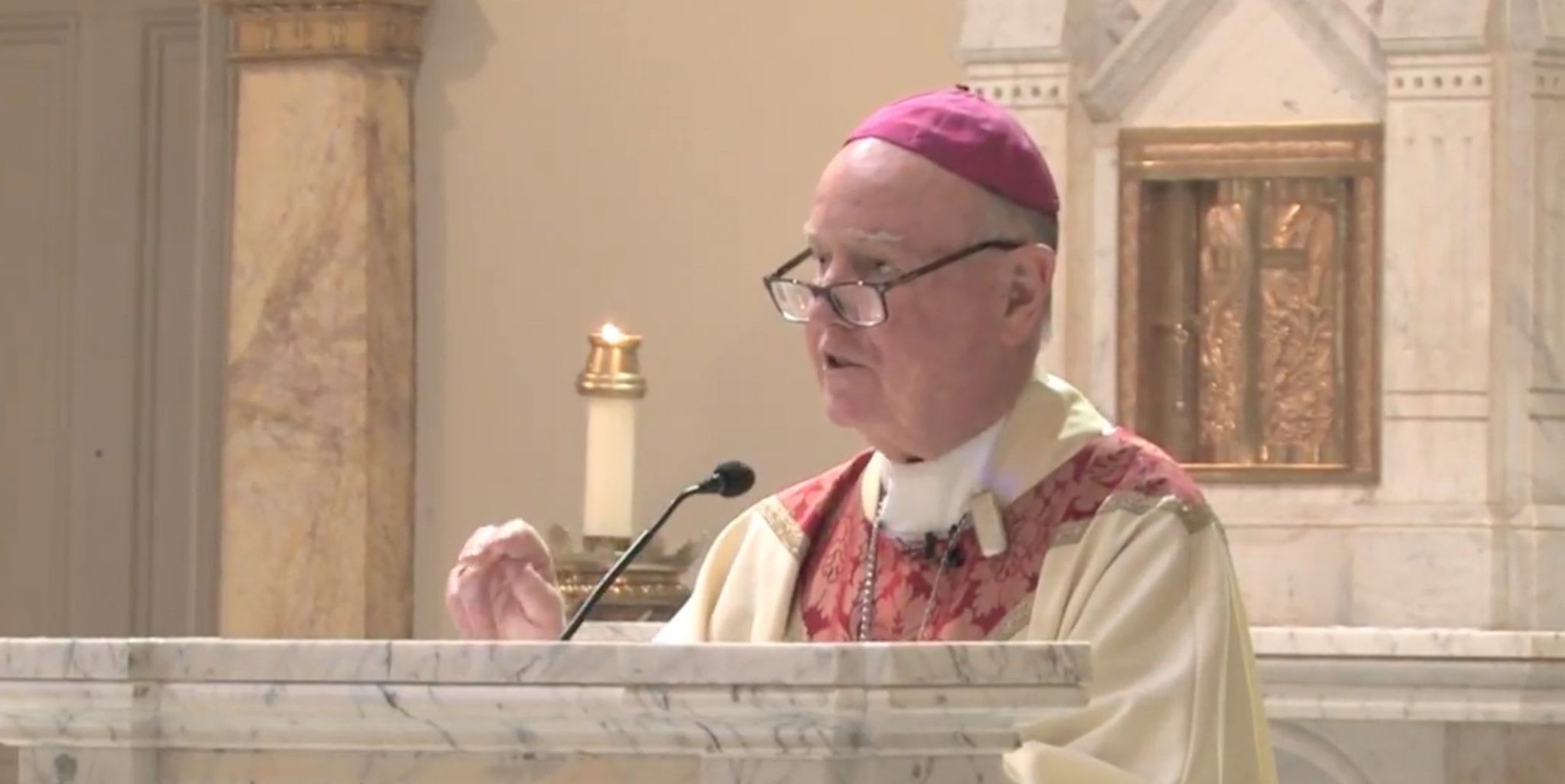

Of course, the Anderson matter is highly relevant, especially in light of Bambera’s possible ambition to succeed Archbishop Charles Chaput in Philadelphia. It is just one more snapshot of a culture under Bambera marked by heterodoxy, cronyism, and indiscipline.