“Why did so few heed Churchill’s warnings about Hitler in the 1930s?” A routine question, it snapped me back instantly to the best answer I ever heard. It was by Sir Alistair Cooke, the great journalist and broadcaster, at a Churchill conference in 1988 in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. He had come to relate his memories of Churchill over 50 years.

Alistair Cooke was a Lancashire boy of 10 when the First World War ended. “It was so vivid to me,” he remembered. “The Lancashire regiments were among the hardest hit — I won’t say ‘decimated’ because there were more than one in 10 killed. Every village in Britain had its war memorial, its long list of names … ”

Later, he fixed his audience of 400 ardent Churchill admirers with a steely eye: “The British would do anything to get rid of Hitler — except fight him. And that was what they perceived Churchill wanted to do. And ladies and gentlemen: If you had been alive and sentient and British then, not one in 10 of you would have been with him.”

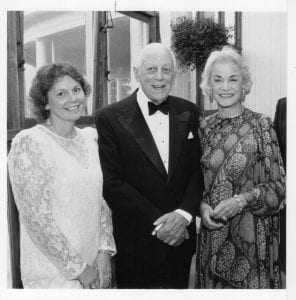

Cooke at Bretton Woods

Our venue was The Mount Washington, scene of the 1944 international conference that had set the world monetary rules we have today. But that was not the reason I invited Alistair Cooke. I’d long admired his background as a reporter, his grasp of affairs among the English-speaking peoples. For 50 years he had conveyed his thoughts, sensitively and serenely, back and forth across the Atlantic. And so we wondered: What did this accomplished reporter observe and think of Winston Churchill?

We were told he had a reputation for being very hard to get, and he was no great fan of fans. (His wife once told me she ran into Cooke’s former wife, who said, “Is Alistair all right? I tried to say hello when I saw him in Grand Central, but he brushed right by me!” At Bretton Woods a hotel guest approached: “Did anyone ever say you look just like Alistair Cooke?” He snorted, “Yes — my mother. Often.”)

To our delight, he defied the odds. “This is the time of year when I turn down everything,” he wrote. “But your letter gave me pause. And, after due consideration of all the insuperable obstacles, I am, like the character in Tennyson, ‘saying he would ne’er consent, consented.’ ” (I replied urging him not to avoid negatives if he deemed them appropriate. As Churchill told an awestruck young editor in the 1930s, “Do not be afraid to criticize — I am a professional journalist.”)

Sir Alistair Cooke at The Mount Washington, Bretton Woods, August 27, 1988.

Retirement Not

Born in Manchester, Alistair Cooke first sighted North America in 1932 at the age of 23. He expected to be here only briefly, but nine years later he became a U.S. citizen. He was American correspondent for The Times of London (1938–42), then United Nations correspondent for the Manchester Guardian (1945–47). On television he hosted Omnibus in the 1950s and Masterpiece Theatre in the 1970s. His greatest TV achievement was America: A Personal History of the United States. It earned four Emmys and led to his best-selling book, Alistair Cooke’s America. “My entire career from the age of 28 to 79,” he wrote, “has been that of reporting America, first to Britain and then to the rest of the world.” Cooke had served the Guardian as U.S. correspondent from 1947 until 1972 when he “retired.”

But he had taken an oath (which I have since vowed to follow): “I shall never retire, because I have observed that most of my friends who do immediately keel over.” So he continued his weekly BBC 15-minute broadcast, “Letter from America.” First beamed only to Britain, it ended up in 50 countries. He began it in March 1946, and for nearly 60 years never missed a week. How did he rate among his peers? Consider the New York Times’s William Safire: “He interprets America better than any foreign correspondent since Tocqueville.”

His acceptance sent me to his 11 books for examples of those interpretations. Most impressive was the relaxed, contemplative tone with which his media audiences back then were familiar. With Alistair Cooke it is like having an old friend to chat with. When he talks of the storms that have rocked our civilization, he reminds one of the old saying: “A friend is someone who knows all about you, but likes you.”

From the Cooke Corpus

Open any Cooke book at random and you are quickly captivated by the quality of the prose and the breadth of understanding. Here for example is what he broadcast in August 1970, on the 25th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Japan:

Without raising more dust over the bleached bones of Hiroshima, I should like to contribute a couple of reminders. The first is that the men who had to make that decision were just as humane and tortured at the time as you and I were later. And, secondly, that they had to make the choice of alternatives that I for one would not have wanted to make for all the offers of redemption from all the religions of the world.

Though always realistic, Cooke was Churchill’s kind of optimist. Both sought silver linings to clouds however stormy. Here is what he broadcast in October 1971, on “the magnificent and munificent idea of the Marshall Plan.” Dean Acheson, its architect, had just died, mostly forgotten. Cooke knew his audience would mainly be composed of people who had never heard of Acheson, or the scheme he devised:

The Marshall Plan was a vast system of loans and gifts to battered old Europe that made possible, not only her recovery — but also, as Secretary of State Dean Acheson was well aware — the healthy growth of a generation of young Europeans with lungs powerful enough to exercise in withering denunciation of this Secretary, who looked like a Spanish grandee and was, they swore, an American imperialist who had spawned the Marshall Plan as a fat insurance racket.

My favorite Cooke-book is his Six Men — along the lines of Churchill’s Great Contemporaries. He knew all six personally: Chaplin, Mencken, Bogart, Adlai Stevenson, Bertrand Russell, and Edward VIII. It is about the latter that I offer my last Cookeism, which I’ve dined out on often. Despite many biographies, and Edward’s own apologia, it is still the best. Everyone who has read Six Men remembers it:

The most damning epitaph you can compose about Edward VIII — as a prince, as a king, as a man — is one that all comfortable people should cower from deserving. He was at his best only when the going was good.

Epilogue: Personal Memories

The magic name of Churchill has happily allowed me to meet some memorable people. Alistair Cooke and his wife, Jane White Hawkes, were certainly among them. The friendship that began in Bretton Woods lasted 16 years. We nursed a fulsome correspondence, now in trust for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. Some letters were serious, some droll, some embarrassing. The worst came when I ran a piece on political cartoonist David Low — stupidly entitled “Sidney Low.” Immediately arrived the inevitable rebuke:

Dear Richard: What an unbelievable & utterly appalling error! Like writing a piece about Henry Bernard Shaw or Franklin D. Kennedy! Sidney Low was an editor-journalist of very little fame. David Low was, indeed, the greatest cartoonist of this century. You must apologize openly & profusely. With (otherwise) kind regards – Alistair

The only thing to do was reply in kind:

Dear Algernon: I apologize utterly and profusely. Of course I have all of Low’s books and cartoons, and I knew perfectly well. Bolloxing Christian names is my notorious fault. I am sure that in future I shall never forget the distinguished name of Mordecai Low as among the greatest scribblers of our time. With regards to you and Janice. Yours ever, Fred Langworth

Christmas at Fifth Avenue

Our last visit was in December 2003, to his Fifth Avenue flat overlooking Central Park. He proudly told us it was previously home to William Shawn, immortal editor of The New Yorker. “I have been housebound for 18 months,” Cooke said, “but I do set aside a half hour in the evening for entertaining friends.” Two hours later we finally left, Alistair ejecting us: “I must eat at a set time every night, or everyone gets upset.”

He was still the man we remembered, stooped and tottery now, but the same witty, brilliant mind. There was the fine grasp of events, the vivacious wife, now 91 but looking more like 70. An accomplished artist, Jane had set down her brushes: “At the moment I’m into full-time maintenance.”

Barbara Langworth (who did all the work at the Bretton Woods conference), with Alistair and Jane.

None of our conversation in December was what one might expect with a 95-year-old, nothing about medicine or doctors or age. Alistair spoke of history, past and current: the U.S. election, the Howard Dean phenomenon, prospects for President Bush. What would happen in Iraq, how Iraq was formed (with Churchill’s assistance). And 9/11 was a not-so-distant memory. (Cooke juxtaposed the “soft brown eyes” with the hard terror of Osama bin Laden.)

A journalist now eight decades on the scene, he spoke with panache, and much less reticence than he would in public. (“___ ___ is a horse’s arse.”) I’m sure he was mulling over his next Letter from America. When he left the room Jane said, “He lives only for the Letter. If he ever has to give that up he will die.”

Three months later we heard his announcement: “Throughout 58 years I have had much enjoyment in doing these talks. I hope some of it has passed over to the listeners, to all of whom I now say thank you for your loyalty and goodbye.” Alistair had finally retired. I remembered what he and Jane had said about that.

“Always, triumphantly, in touch”

His friend William F. Buckley Jr. wrote that Churchill College, hearing that he had “put his feet up,” invited Alistair to be a Trustee. Cooke replied, “Thank you for your invitation. In about two months, I will put my feet up permanently.” He thought this “very funny, which indeed it was,” Buckley wrote, “very nearly, though not quite, dispelling the gloom in his visitor’s heart.”

His old paper, the Guardian, knew him best:

Was he a great journalist? Just read his coverage of Kennedy in Dallas: the question answers itself. He could reach heights few others could aspire to. But did he — for the millions who tuned in, decade after decade — reflect any America but his own, a mix of nostalgia, Mencken and Rockwell reheated? That is a harder question…. In extreme old age, the laughing cavalier could do so much more than remember. He could reach back, reach forward: and make the connections. He was always, triumphantly, in touch.

Which for me made his death no less easy to accept. As Churchill wrote of Arthur Balfour, “I felt also the tragedy which robs the world of all the wisdom and treasure gathered in a great man’s life and experience and hands the lamp to some impetuous and untutored stripling, or lets it fall shivered into fragments upon the ground.”

Game Called …

upon the field of life

the darkness gathers far and wide,

the dream is done, the score is spun

that stands forever in the guide.

Nor victory, nor yet defeat

is chalked against the player’s name.

But down the roll, the final scroll,

shows only how he played the game.– Grantland Rice

Mr. Langworth is Senior Fellow at the Hillsdale College Churchill Project.