The recent wave of protests in Iran has been widely portrayed in the American media as an ideological uprising — a struggle for freedom, democracy, or secular governance. Some commentators have gone further, treating the unrest as an early sign of regime collapse.

History does not intervene because people suffer. It turns only when the structure of force changes.

This interpretation is comforting, but it is deeply misleading.

What is unfolding in Iran did not begin with ideology. It began with economic collapse. And how it ends will not be decided by the depth of public anger, but by a far more brutal question: whether the state is willing to kill to survive.

A Small Bank With Enormous Consequences

The immediate trigger of the protests was the collapse of Ayandeh Bank, a financial institution that was not systemically important in the conventional sense. On the surface, it looked like yet another banking failure in a troubled economy.

In reality, Ayandeh represented something much more corrosive: a textbook case of insider finance in an authoritarian system.

Ayandeh’s largest investment was Iran Mall, which opened in 2018 — at a time when much of Iran’s economy was stagnating, inflation was accelerating, and ordinary Iranians were seeing their living standards collapse. The project was not merely large; it was grotesquely extravagant. Covering an area twice the size of the Pentagon, Iran Mall functions as a “city within a city,” complete with IMAX theaters, libraries, swimming pools, sports facilities, indoor gardens, auto showrooms, and a “Mirror Hall” modeled after a 16th century Persian royal palace.

The problem was not luxury as such. The problem was where the money came from.

Economists and Iranian officials have described Iran Mall as a classic case of “self-lending.” Ayandeh Bank was effectively lending depositors’ money to companies it controlled. The bank was both lender and borrower; risk stayed on the balance sheet, while any potential gains accrued to the same elite network. When the bank collapsed, Iran’s semi-official Tasnim News Agency quoted a senior central bank official as saying that more than 90 percent of Ayandeh’s resources were tied up in projects it managed itself.

This was not mismanagement. It was systematic extraction.

Printing Money Is Not Rescue — It Is Confiscation

When Ayandeh’s finances imploded, the losses were not absorbed by those who had benefited. The government stepped in, took control, and filled the hole by printing money. Officially, this was described as stabilizing the financial system. In reality, it was something else entirely: the socialization of elite losses.

The result was runaway inflation.

Iran’s economic crisis had been building for years, but it sharply accelerated over the past several months. In 2025 alone, the Iranian rial lost 84 percent of its value against the U.S. dollar. Food prices rose 72 percent year over year, nearly twice the average rate of recent years.

Inflation here was not an abstract macroeconomic phenomenon. It was an instrument of silent expropriation. Ordinary Iranians saw their savings evaporate almost overnight. Wages lagged far behind prices. Money held in bank accounts became functionally worthless — not through confiscation, not through taxation, but through dilution.

This is the core of public anger in Iran. People understand that their property was not lost because “the economy is bad,” but because a network of power, banks, and state money creation quietly transferred wealth upward.

This is not about ideology. It is about survival.

Misery Does Not Automatically Topple Regimes

Under such conditions, protests are unsurprising. When people are pushed far enough, they will resist. But here is the most uncomfortable truth — one that Western commentary often avoids: Economic collapse, corruption, and mass suffering do not automatically bring down authoritarian regimes.

History shows this again and again. Desperation can produce revolt, but revolt does not succeed when the state possesses overwhelming force and is willing to use it relentlessly. In those cases, resistance does not end in revolution; it ends in death.

Why the Soviet Bloc Collapsed — and China Did Not

This is why any serious analysis of Iran must return to comparative history.

The Soviet Union and Eastern European communist regimes collapsed between 1989 and 1991 not because their economies suddenly worsened or because people became braver, but because the leadership refused to order mass killings. Mikhail Gorbachev would not command the army to fire on civilians, and Eastern European regimes depended on Soviet backing as their ultimate coercive guarantee. When that guarantee disappeared, the entire structure collapsed almost instantly.

China followed a different path.

The Chinese Communist Party survived because it chose to use lethal force — and demonstrated that it was prepared to do so without hesitation. From that moment on, the regime sent a clear message: resistance would be met with death. Politics ceased to be negotiation and became deterrence. Discontent did not vanish; it was crushed.

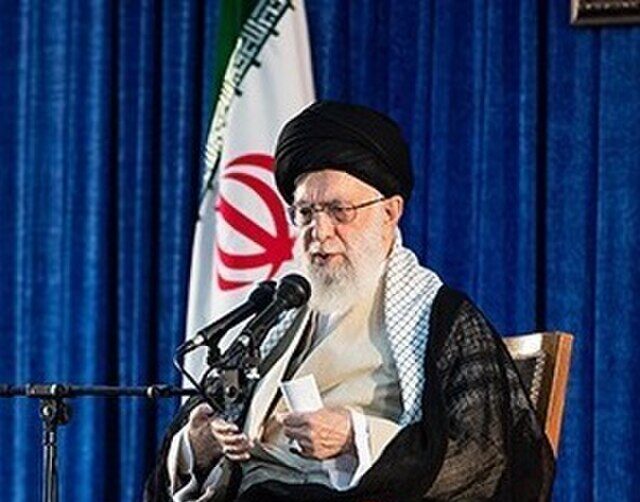

Iran’s Choice Is Becoming Clear

Iran is now approaching this same fork in the road.

The regime has begun deploying what regime scholars call the “knife handle” — the judicial and security apparatus (as opposed to “gun barrel” — the military). Courts have accelerated trials, imposed long prison sentences, and carried out executions. Protesters are being redefined not as dissidents, but as enemies of the state and religion. Law is no longer a constraint on power; it has become power’s formal instrument.

The knife handle and the gun barrel serve the same purpose. One institutionalizes fear; the other enforces it. Together, they can suffocate mass mobilization with chilling efficiency.

This is not a moral argument. It is a political reality.

Of course, whether the United States intervenes is a crucial external variable — one that could decisively alter the outcome. But even here, the logic should not be misunderstood. If outside intervention changes Iran’s trajectory, it will not be because “justice has finally defeated evil,” but because an existing structure of violence has been broken by a stronger one. History does not turn simply because suffering deepens. It turns only when power — especially coercive power — shifts hands.

Conclusion: Failed States Do Not Collapse by Themselves

Iran today is governed by a regime that is deeply corrupt, economically hollowed out, and increasingly incapable of providing material stability. It is also a regime that has demonstrated its willingness to confiscate wealth through inflation and suppress dissent through force.

Such a regime does not collapse simply because it has failed.

As long as it controls the instruments of violence — and as long as those instruments remain loyal — it can continue ruling over ruins. North Korea has already proven this. Extreme poverty, total repression, and economic dysfunction are entirely compatible with long-term regime survival.

Iran’s real test is not how angry its people are. It is where the guns are pointed.

History does not intervene because people suffer. It turns only when the structure of force changes.

Shaomin Li is professor of international business at Old Dominion University