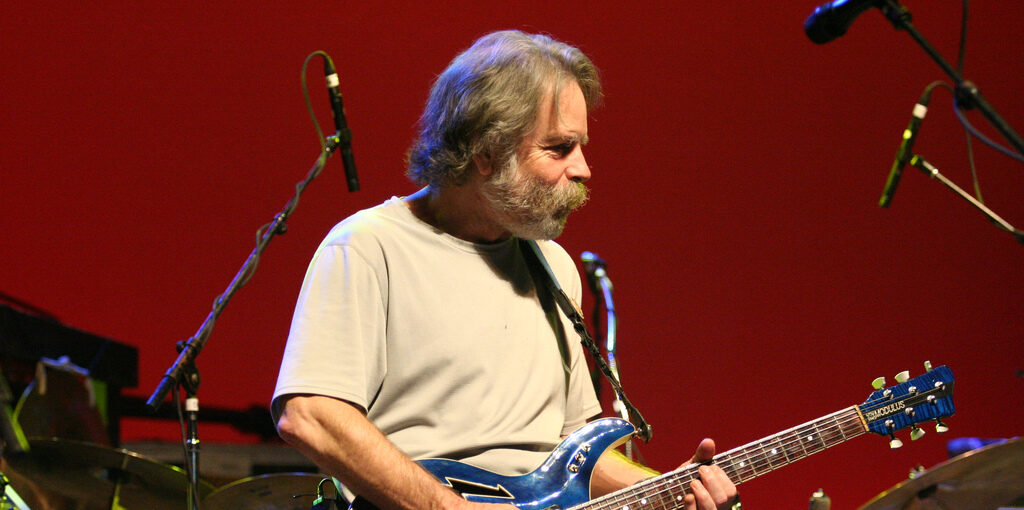

When I first saw the Grateful Dead play, I was just shy of 17, on December break, my junior year in high school. Bob Weir, who just passed away last week, was 21 at the time, close enough in age to identify with, both then and now as well.

He always approached his work and his audience with unpretentious love.

I’ve spent most of my adult life studying Judaism’s classic texts and practicing and teaching its truths to the best of my ability. Why I am writing for a second time about founding members of the Grateful Dead on their passing?

I’ll give the brief version, which must suffice for now. The Grateful Dead scene was the catalyst for my journey into my calling. I can’t think I would have traveled the road I did were it not for the beauty and power that was present in that scene (along with plenty of other all-too-human foolishness, for as the rabbis of old taught, no one sins until a spirit of foolishness enters them).

That scene had the great good fortune of attracting the attention of a formidable talent to chronicle its birth, Tom Wolfe. Satirist non pareil, the man who identified and skewered wokeness long before it even had that name, Wolfe was attracted to the wildness of the scene that emerged around Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, and wrote about it in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Kesey was a young married grad student in Stanford’s creative writing seminar along with such others as Larry McMurtry and Wendell Berry. To make a few bucks, he volunteered to be an experimental subject to find out the properties of some new drugs (later, it FOIA requests showed the test was covertly run by the CIA, who were seeking to find out what drugs might disorient enemies). That’s where Kesey met up with LSD, completely unknown and still perfectly legal. Kesey was so impressed that he found ways to get hold of it himself and share it with friends.

As Wolfe writes, Kesey’s early parties eventually morphed into free-form events open to the public, featuring an immersive atmosphere. Driving them was the rock and roll band Kesey invited, a brand-new group called the Grateful Dead. As much as their sound shaped the event, the event shaped the band and set it on its course.

Wolfe writes about the scene developing a religious core, in the midst of the wildness. He quoted one of the slogans that Kesey and his crew would use to guide themselves — “Put your good where it will do the most!” and then noted:

Gradually the Prankster attitude began to involve the main things religious mystics have always felt, things common to Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and for that matter Theosophists and even flying-saucer cultists. Namely, the experiencing of an Other World, a higher level of reality. And a perception of the cosmic unity of this higher level. And a feeling of timelessness …

This had been noted by other writers who had experimented with psychedelic drugs (all still legal) in the previous decades. Aldous Huxley, the author of the prophetic, dystopian Brave New World, wrote about his experience taking mescaline, as well as the role of peyote (the natural source of mescaline) in the worship practices of some Native Americans:

Sometimes they hear the voice of the Great Spirit. Sometimes they become aware of the presence of God and of those personal shortcomings that must be corrected if they are to do His will.

The philosopher and theologian Alan Watts wrote in a similarly serious way about his LSD experiences, just a few years before the Acid Tests.

But something more than seriousness is needed for true religious breakthrough. Jordan Peterson specified that in his portrayal of God’s calling to Abraham as the beckoning spirit of adventure. The pursuit of truth is adventure of the highest sort.

Adventure it was for Kesey and those who joined in. Instead of writing books about the experience, they undertook to share it in all its wildness and compelling power. They evolved a repeatable free-form gathering in which people were improvising music, light shows, open mics, and costumes, all designed to break through together into a higher vision. Religious vision all mixed in with a party groove and musicians following the vision in the moment in the tradition of American improvisational music — and at fifteen years old, Bob Weir was in the center of it.

Weir described himself in those early days as an “acid evangelist.” As one of the early original songs of the Grateful Dead went, “It’s a party every day.” People in the party felt it was much more than a party, so the band tried to bring the party to everyone. In the words of the Martha and the Vandellas hit that Bob sang in those heady days:

Everywhere around the world

Get ready for a brand-new beat…This is just an invitation across the nation

A chance for folks to meet

There’ll be laughing, singing, and music swinging

Dancing in the street…All we need is music, sweet music

There’ll be music everywhere

There’ll be swinging, swaying

And records playing and

Dancing in the street.

But the flowering of early days fell apart. The Haight Ashbury district, where Weir lived in a house with his bandmates for a while, collapsed into a grim area of addicts selling whatever they could for meth and heroin. Woodstock within half a year morphed into Altamont, the rock festival of bad vibes and murder that went so bad that Weir and his bandmates closed it down before they even took the stage.

In a song written about that time, the band looked at the darkness and vowed to carry on.

One way or another

One way or another

One way or another

This darkness got to give.

A limit had been reached. Not everything in life can be experimented with. Whatever power drugs had, they could not substitute for what people had to bring from the depth of their souls. There is a need for the disciplines of storytelling and songs, things which can be passed down and repeated without losing their light.

The religious theme had been taken up directly by the band before. Great shows from their late Sixties experimental music era would often end by facing the terrifying realities of life through a song by the Harlem street preacher, Rev. Gary Davis: “Death Don’t Have No Mercy in This Land,” leading eventually to an a capella rendering a Bahamian gospel tune, “I Bid You Good Night.”

But after Altamont, the band turned a corner into Americana; short, crafted story-songs that summoned up the spirit of real America, dipping deep into blues and country and western and old-fashioned rock and roll. Weir stepped forward with a classic rock feel, joining Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly to look at America’s love of music and good times with cosmic affection. In lyrics which he wrote, Weir would place Saturday-night America into the mind of a joyous divine MC:

Then God way up in Heaven, for whatever it was worth

Thought He’d have a big old party, thought He’d call it Planet Earth

Don’t worry about tomorrow, Lord, you’ll know it when it comes

When the rock and roll music meets the risin’ Planet Sun.One more Saturday night!

Around this time, Weir went to Harlem to meet Reverend Davis, and he picked up a song of the reverend’s that became permanent in the repertoire: “Samson and Delilah,” a powerful retelling of the tale from the Book of Judges in a rock and roll idiom, with the chorus a prayer of Samson’s:

If I had my way

If I had my way

If I had my way

I would tear this old building down.

Around this time, Ken Kesey was facing the darkness by writing his list of “tools from the chest” that were of proven worth in facing the darkness in life. As a dedicated scene member, I bought his new offering hot off the press. The first tool he wrote about was the Bible, which he strongly recommended everyone to read from every day for the rest of their lives. As well, he wrote about the modern Jewish mystic, Martin Buber, whose insights in the book I and Thou he felt could change everyone’s life for the better.

This turn towards tradition at first shocked me, but I soon took it into heart and practice. Just as the musicians in Kesey’s house band were deepening their roots in the musical traditions in which they had first trained themselves, so Kesey was pointing to the religious traditions, in their broadest sense, that had carried forward the entire endeavor of human life and all its aspirations.

I took Kesey’s advice and soon found myself deep in the tradition to which I had been born, and grateful for being able to see all of it through fresh eyes. In a song that Bob Weir composed, he sang lyrics about the music as he and we felt it: “The music plays the band.” That esthetic keeps religion alive as well. It seems aligned with Martin Buber’s conception of the most important choice we make is — do we relate to the others in our lives as mere useful instrumentalities or are they shaping us even as we shape them, and we all together are joined by the divine purpose permeating all things? The latter opens us up to being a letter in the scroll, a player in the music.

While that did set me on a well-worn professional path, it did prepare me for life as an unfolding adventure. It did prepare me to listen to the music playing in others’ lives. It did give me an acute sense of the musicality of religious life as people live it, seeking to give voice to the indispensable connection each moment begs for us to do and to be the word in action, making a life of ever-deeper harmony, undeterred by any dissonance.

Bob Weir developed his music in response to this deep drive, coupling an ever-growing dedication to craft to his keen sense of fun. The band tried to fire him back in 1967, thinking him not capable of growing as they were. He refused to be fired, just kept coming to rehearsals, and didn’t stop listening or improving.

He made something unique out of his rhythm guitar, sounding like John Coltrane’s stellar pianist McCoy Tyner in setting down a framework of chords upon which the twisting vines of Garcia’s solos enwrapped themselves and grew tall. He wrote songs with weird time signatures that rocked. He wrote suites that held the attention of rock audiences. He always approached his work and his audience with unpretentious love.

And in the end, he had the respect of his own craft. His bandmate from the start, drummer, Bill Kreutzman, wrote of him this week:

I once heard Bobby refer to himself as “the greatest rhythm guitar player in the world” and it made me chuckle lightheartedly at my brother’s boastfulness. The thing is … he was probably right.

In the end, what more was there for him to do? He played it all … and never the same way, twice. I think he had finally said everything he had to say and now he’s on to the next thing. I just hope he was able to bring his guitar with him or otherwise he’ll go crazy.

And the last word, with a loud amen, will go to Paul McCartney, just seen on the feed today:

Bob Weir was a great musician who inspired many people of many generations.…

His humour, friendship and musicianship inspired me and will inspire many people into the future. Our family’s thoughts go out to Bob’s family at this time of loss, and I know they will remain as strong as he would wish them to be.

God bless you, Bob. See you down the road. Love Paul

READ MORE from Shmuel Klatzkin: